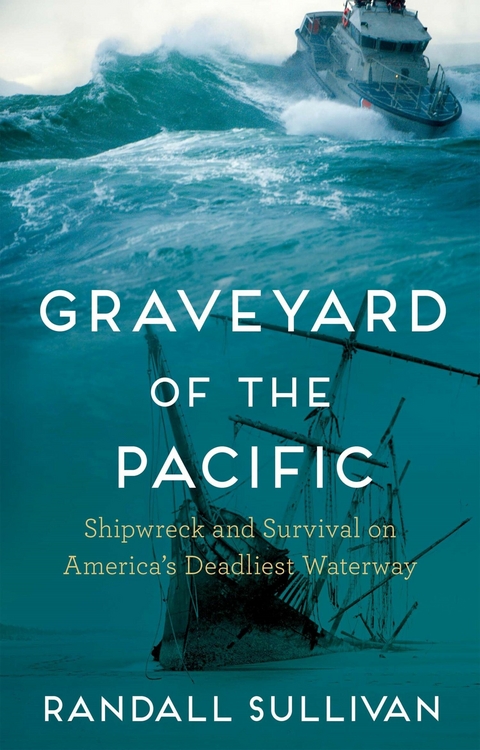

Graveyard of the Pacific (eBook)

272 Seiten

Grove Press UK (Verlag)

978-1-80471-037-1 (ISBN)

Randall Sullivan was a contributing editor to Rolling Stone for over twenty years. He is the author of Dead Wrong, The Price of Experience, LAbyrinth, The Miracle Detective and Untouchable. His work has been published in, among many other places, Esquire, Outside, Men's Journal, Washington Post and the Guardian. He lives in Oregon.

Off the coast of Oregon, the Columbia River flows into the Pacific Ocean and forms the Columbia River Bar: a watery collision so turbulent and deadly that it's nicknamed the Graveyard of the Pacific. Two thousand ships have been wrecked on the bar since the first European ship dared to try to cross it in the late 18th century. Since then, the commercial importance of the Columbia River has only grown, and the bar remains a site of shipwrecks and dramatic rescues as well as power struggles between small fishermen, powerful shipowners, local communities, the Coast Guard and the Columbia River Bar Pilots - a small group of highly skilled navigators. When Randall Sullivan and a friend set out to cross the bar in a two-man kayak, they're met with scepticism and concern. But on a clear day in July 2021, when the tides and weather seem right, they embark. As they plunge through the currents that have taken so many lives, Randall commemorates the brave sailors that made the crossing before him - including his own abusive father - and reflects on toxic masculinity, fatherhood and what drives men to extremes.

Randall Sullivan was a contributing editor to Rolling Stone for over twenty years. He is the author of Dead Wrong, The Price of Experience, LAbyrinth, The Miracle Detective and Untouchable. His work has been published in, among many other places, Esquire, Outside, Men's Journal, Washington Post and the Guardian. He lives in Oregon.

THE GREAT RIVER OF THE WEST was born from violence, from fire, and from ice. Fire came first. More than 250 million years ago, when most of the landmass of Earth was contained within the supercontinent Pangea, superheated liquefied rock, magma, burned a three-pronged rift through the crust and began the tectonic separation of North America, Europe, and Africa. As the new continents drifted apart, somewhere between one hundred million and ninety million years ago, the movement of plates floating atop a fiery mantle pushed long chains of active volcanoes hard against the upper left edge of North America, a scorching fusion that created what is now the Pacific Northwest.

The future basin of the Great River was surrounded then by the continuously bubbling, spewing, spreading eruptions of the young mountains that shaped the original configuration of a track flowing out of what is now Canada toward the Pacific Ocean. It was the molten lava that pulled the moisture out of the Earth’s interior and left water on the planet’s surface as it cooled. An ancestral version of the river was soon descending from a long, sunken fault line that would become the Rocky Mountain Trench.

The Rockies themselves rose as massive upwelling explosions between eighty and fifty-five million years ago, and off their western flanks sent huge flaming flows of basalt lava south to push out an inland sea and shape the path of the still-forming Great River beneath it. The Cascade Mountains are much younger than the Rockies—they did not uplift out of the Earth’s mantle until five to four million years ago—but they were also enormous fulminations that further seared and shifted the region’s topography, helping to define the outline of an immense waterway.

Then, about thirty-three thousand years ago, North America’s volcanic fires were overtaken by a rapid expansion of ice spreading south, caused, scientists believe, by a shift in the Earth’s orbit around the sun. Five thousand years later, much of North America was under two enormous ice sheets. The one to the west, the Cordilleran, covered at its maximum nearly two million square miles of land, stretching from Alaska to Montana, and may have reached as far south as the northeast corner of Oregon.

That ice is what put the finishing touches on the formation of the Great River. The gouging of glaciers moving south and west did a good bit of the work, but it was the melting of the ice that had the greater effect. Around nineteen thousand years ago, when the glaciers began to once again retreat, a gigantic frozen wall, an ice dam, embanked an enormous body of fresh water that geologists call Glacial Lake Missoula. The gargantuan pond was two thousand feet deep then and about the size of today’s Lake Ontario. On at least forty occasions between nineteen and thirteen thousand years ago, the ice dam that held back Lake Missoula failed. The resulting floods were epic on a scale that defies human imagination. Each one unleashed more water than was in all of the Earth’s rivers combined, scouring its way through mountain ranges to inundate an area of sixteen thousand square miles to a depth of up to several hundred feet. In the center of the flood path was what would become the bed of the Great River. When the waters receded, the ultimate course of that river, and of its connection to a vast system of tributaries, was left behind.

Where the river began then was where it does now, spilling out of the remnant of a smaller glacial lake that had been swept up into the Lake Missoula floods. Situated today in southwestern Canada, the lake bears the name of the river it has spawned, Columbia.

Given the underlying law of rivers—water runs downhill—it’s surprising that the headwaters of the Columbia River are at a modest elevation of 2,690 feet. The Columbia’s long descent to the ocean, though, is not only expanded but also hastened by the rivers, creeks, and streams pouring down into it from the mountains on both sides.

Curiously—one is tempted to say, perversely—a river that for most of its more than twelve-hundred-mile length flows south and west begins by heading north for 218 miles in a detour around the Selkirk Mountains, taking in, among other lesser tributaries, the icy Spillimacheen River that plunges down from the eastern edge of Glacier National Park, dropping nearly six thousand feet in elevation in fifty miles before pouring out of the rocks like a long waterfall into the Columbia. Then, at what has become known as the Big Bend, just above the northern reach of the Selkirk Range, the river makes a dramatic reversal of course, turning sharply almost due south as it drops through Canyon Hot Springs.

Soon after, sixty miles above what is now the United States border, and still headed south, the Columbia is joined by its first truly major tributary, the Kootenay River, 485 miles long and draining an area of more than 50,000 square miles, dropping 6,600 feet in elevation from its headwaters on the northeast side of the Beaverfoot Range before it merges with the greater river. Flowing through and alongside steep mountains, the Kootenay collects the waters of its own sizeable tributaries, including the 128-mile-long Duncan, before emptying them into the flow of the steadily swelling Columbia.

A thousand years ago, two large tribes lived in this area, on each side of what they called, in different tongues, Big River. To the west were the Sinixt, the Lake People, inhabitants of the region for ten thousand years, whose dwellings during the winter months were half-buried houses. East of the Columbia, the Kootenai nation used an “isolate language”—one that had no relation whatsoever to those spoken by neighboring tribes; some scholars contend that their ancestors migrated from what is today the Michigan side of Lake Superior. The Kootenai traveled the rivers in canoes as original as their language, made of dug-out cedar logs with pine bark on the bottom and birch bark at the gunwales, remarkable mainly for the way both ends were bent sharply inward, the same on one end as on the other, so that when spinning in rapids there was no definite front or back.

South of what is now the border between Canada and the United States, the Columbia is joined by the Pend Oreille and the Spokane, rivers that between them drain nearly 34,000 square miles stretching across Montana, Idaho, and Washington. The Big River continues west until its confluence with the 115-mile-long Okanogan River, then turns south again on a stark but achingly beautiful granite plateau where rattlesnakes live among sagebrush, prickly pear cactus, and tumbleweed.

Passing through the arid but fertile plain of central Washington State, the Columbia absorbs yet another large tributary, the 214-milelong Yakima River, one more part of the Big River’s system that bears the name of the people who lived there before the arrival of Europeans.

Nearly forty miles south of the Yakima, the Columbia’s largest tributary, the Snake, a great river in its own right, adds the waters it has collected from six US states and a drainage area of more than one hundred thousand square miles. The Snake is smooth and wide where it enters the Columbia in today’s southeastern Washington, but for most of the 1,078 miles behind it the river is as dramatic as any on the continent. Beginning at the confluence of three tiny streams in what is now the Wyoming section of Yellowstone National Park, flowing west and south into Jackson Hole, through the most spectacularly lovely mountain range in America, the Tetons, the Snake crosses plains and deserts as it turns up, then down, then up again across the entire width of Idaho before entering what is possibly the most impassable section of river on the planet, Hells Canyon, a 7,993-foot gorge (North America’s deepest) forming what is today the eastern border of Oregon, which separates it from Idaho and Washington.

The people most associated with the Snake River are the Nez Perce. Powerful in war and trade, the Nez Perce nation lived in seventy separate villages, inhabited a territory of seventeen million acres, and networked with other tribes all the way from the Pacific shores of present-day Oregon and Washington to the high plains of Montana to the Great Basin part of Nevada.

Nearly a mile wide by now, the Columbia moves more slowly west through the lava plateau on both sides of it, taking in, among other rivers, the 252-mile Deschutes and the 284-mile John Day. The Great River narrows and accelerates as it enters the gloriously lovely Columbia Gorge, a four-thousand-foot deep, eighty-mile-long canyon with what is now Oregon on the south shore and Washington on the north. As the gorge deepens, the river’s run passes from grasslands marked by widely spaced lodgepole and ponderosa pines into a thick rainforest of firs and maples that tower on the cliff face above. The deepest cut of the gorge is a wind tunnel that propagates howling snow and ice storms during winter months. Waterfalls abound on both sides of the river in the gorge, and one of them, Celilo, was not only a prime fish-catching spot but the main trading station between the upriver tribes that spoke the Sehaptian tongue and the peoples downriver that spoke the Chinookan language.

Passing through the gorge, the river is headed to where its truly great wealth lies. The Columbia’s size is of course part of what makes it a great river. Only the Missouri/Mississippi system exceeds it in annual runoff, and there are years when the Columbia’s flow is greater. Both of America’s major river systems work off the “tilt” of the Continental Divide, one running toward the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 3.8.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Sammeln / Sammlerkataloge | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Segeln / Tauchen / Wassersport | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Adventure • coastguard • Columbia Bar • Columbia River Bar • fisherman • Fishermen • Maritime • Maritime History • Memoir • Northwest • Oregon • Pacific Northwest • Washington • waterways |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80471-037-7 / 1804710377 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80471-037-1 / 9781804710371 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich