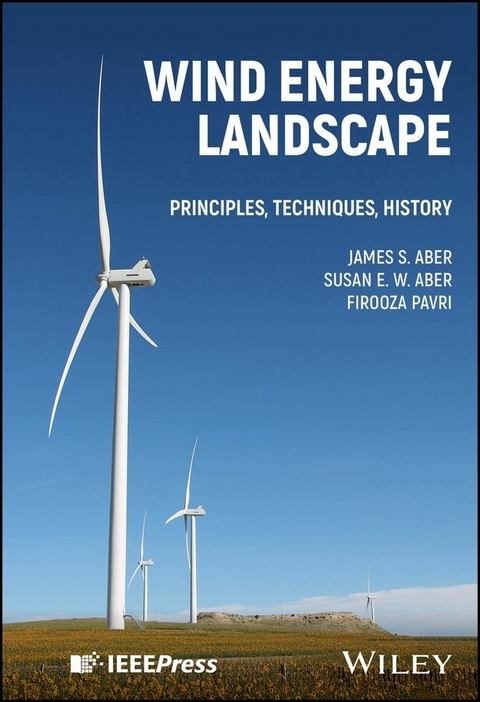

Wind Energy Landscape (eBook)

304 Seiten

Wiley-IEEE Press (Verlag)

978-1-394-21289-7 (ISBN)

Fully illustrated and accessible reference covering the background, current state, and future opportunities for wind energy development

Wind Energy Landscape presents a comprehensive treatment of wind energy history, principles, and techniques as well as environmental, health, aesthetic, social, and political impacts. Focusing primarily on the European and North American markets with additional reviews from Asia, this book enables readers to gain a practical overview and understanding of modern wind energy, supported by in-depth case studies throughout.

Fully illustrated with maps, satellite images, drawings, and photographs taken on the ground or via kite aerial photography, this book disproves many myths about wind energy-such as by demonstrating that wind farms may exist in rural land or offshore settings with minimal impacts-and promotes the radical-middle approach for integrated and evolving energy resources in which wind power has come to play a prominent role. The authors suggest that wind power in global energy development should be given prominent treatment, particularly for renewable, non-polluting energy sources.

Wind Energy Landscape discusses topics including:

- History of wind energy electricity generation through the late 19th and 20th centuries

- Environmental and aesthetic issues, including impacts on wildlife such as birds and bats as well as visibility and turbine noise

- Public policy for wind energy, covering subsidies, financial and import-export incentives, feed-in tariffs, local-content requirements, and R&D investments

- Energy production and consumption of wind energy in comparison to nuclear energy, solar energy, and hydro and tidal energy, as well as fossil fuels including coal, oil, and natural gases

Bridging the gap between advanced engineering and popular books, Wind Energy Land-scape is an essential reference on the subject for students in introductory courses on electrical, mechanical, and aerodynamic engineering, engineers working with renewable and sustainable energy, and public policy makers.

James S. Aber, PhD, Roe R. Cross Distinguished Emeritus Professor, Emporia State University, Kansas, USA. Professor Aber's interests and research experiences spread across energy resources, geology, landscape evolution, aerial photography, and wetland environments.

Susan E. W. Aber, PhD, is the former Director of the Science and Math Education Center and Peterson Planetarium at Emporia State University (ESU), Emporia, Kansas, USA. Dr. Aber's interests are mineralogy, gemology, and energy resources as well as maps and GIS for librarians.

Firooza Pavri, PhD, Professor of Geography and Associate Dean, Edmund S. Muskie School of Public Service, University of Southern Maine, USA. Professor Pavri's teaching and research interests include environmental change, resource and energy management, and remote sensing.

Wind Energy Preface

The radical middle is where the solution to our energy challenges lies (Tinker 2013, p. 8).

Emergence of Wind Energy

People have harnessed the power in the wind since ancient times. Sailing, traditional windmills, and kites are just a few common examples found around the world. From the twelfth century until the early 1900s, in fact, traditional windmills provided significant motive power for grinding grain, pumping water, running small machines, and performing myriad mechanical tasks in many locales (Fig. P1). The Industrial Revolution stimulated development of new forms of energy derived mainly from fossil fuels along with widespread generation and use of electricity for diverse applications in modern society.

Coupled with rapid growth of human population, energy production and consumption increased even more quickly during the twentieth century in order to raise living standards and health for billions of people. Most people believed that cheap energy from coal, oil, gas, and uranium would fuel the future at low cost with trivial environmental consequences and minimal risks. While this situation appears naive in the twenty‐first century, it seemed quite reasonable in the past. However, the era of low‐cost energy is just a distant memory, environmental issues have come to the forefront, and risks of fossil and nuclear fuels are now recurring themes.

The use of wind power for generating electrical energy has grown phenomenally during the past half century from negligible in the 1970s to more than 1,000 gigawatts (GW) capacity today (GWEC 2024). With this rapid growth came recognition of the windscape, which is the combination of local climate and geography, environmental and ecological conditions, economic incentives and public policies, human land use and infrastructure, as well as historical and cultural expectations associated with harnessing wind power (Aber et al. 2015). Such an integrated approach to assessing the wind‐energy sector would allow for a full accounting of its costs and benefits and enable more efficient long‐term planning strategies (Fig. P2).

Figure P1 Traditional Dutch‐style windmill at Trönningenäs, Halland, southwestern Sweden. The windmill dates from 1899; it has been fully restored and remains functional. When in operation, cloth sails cover the wooden frameworks of blades.

Figure P2 Typical windscape on the High Plains in southwestern Kansas. Mixed agricultural land use and GE Wind 1.5 MW turbines in the original Spearville wind farm that went online in 2006. The nearest turbine stands less than 200 m from the farmstead (on left). Such close spacing is generally not allowed in newer wind farms. Kite aerial photograph with Unruh and Leiker (2008).

Role of Wind Energy

Wind energy has emerged from an uncertain niche industry to become an important component of national energy policies in many developed and developing countries. The case for increased wind power is based on several issues.

- Cost of fossil fuel—The supply and pricing of fossil fuels (oil, gas, coal) have been highly volatile since the 1970s. The long‐term trend is for higher prices, but with wide market swings depending on slight imbalances in supply and demand.

- Dependence on foreign sources—Mass transfer of wealth to foreign sources of fuel is a severe economic drain, and uncertainty of supply for political or economic reasons jeopardizes national security for many developed and developing countries.

- Greenhouse gas emissions—Producing and burning fossil fuels emit large volumes of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Coal is the worst offender in this regard, and coal‐fired power plants are the major sources of electricity in many parts of the world.

Homo sapiens are transforming the Earth through vast land conversions, immense use of minerals and fossil fuels, intense water consumption, and exploitation of many other non‐renewable land and marine resources. This development has been costly for the natural environment. Human activity is largely uncontrolled; most decisions are made for immediate individual survival, gain, or comfort rather than the greater good of society or long‐term environmental sustainability of the world. Nonetheless, increased generation and delivery of electricity are key ingredients for economic development and human quality of life.

In the future, wind energy undoubtedly will play a critical role in the mix of renewable energy sources for countries with substantial natural wind resources and the necessary technological infrastructure and support policies. In well‐developed, relatively small, homogeneous countries such as Denmark, Sweden, Ireland, and Portugal, wind energy could meet up to half of total electrical needs. For larger countries, such as China, India, and the United States, wind energy could reach 20–30% of total generating capacity, but probably not much more is realistically feasible given their diverse geographic, demographic, and economic conditions. For all countries, capacity‐resource generation based on fossil and nuclear fuels will be necessary for the foreseeable future to meet increasing baseload and peak‐load electricity demand.

Building Sustainable Energy Futures

The Merriam‐Webster definition of the term sustainable refers to the ability to last or continue for a long time. The term’s more commonplace usage in policy and science harks back to its introduction in the United Nations’‐commissioned Brundtland Report on Environment and Development, which argued for a new approach toward economic growth and development (Brundtland 1987). Sustainable development recognizes the critical interactions between natural and social systems that links human well‐being with an environmentally conscious approach to economic development, and that, above all, focuses on meeting the needs of current and future generations.

The ubiquitous use of the term sustainability today suggests not only a deep resonance with the public, but more importantly the education of a generation since its introduction. Moreover, the now generally accepted interdisciplinary academic field of sustainability science provides the framework for a more rigorous and problem‐driven, science‐based study of general ideas encapsulated within the term (Kates et al. 2001; Clark and Dickson 2003; Clark 2007).

The global recognition of the role of conventional fossil fuels and greenhouse gas emissions in human‐induced climate change has prompted a strong push for the use of alternative, more benign and renewable, sources of energy, of which wind energy has become a major resource (Aber et al. 2015). Energy demand will continue to increase as such countries as China, India, and Brazil fuel their social and economic development goals. Even with calls for a sustainable path to development, the reality for these and other developing nations is to meet the current needs of their citizens. Even so, alternatives to the current energy system do exist and are now being pursued to varying extents by countries across the globe (Fig. P3). Countries also recognize the distinct local advantages of investing in renewables for regional economic growth (Lewis and Wiser 2007). Not only does it help improve energy access and security, in the long run it may also help reduce the dependency on fossil fuels.

A multi‐pronged strategy, the so‐called radical middle, could help secure a country’s energy future (Tinker 2013). Energy productivity may be enhanced through promoting conservation, securing efficiencies in manufacturing, transportation, and household use. At the same time, however, a pronounced shift to renewable sources such as wind energy, where appropriate, should also be emphasized in order to provide for a balanced and sustainable energy portfolio that exploits the strengths of each type of energy resource.

At present, the wind‐energy sector requires long‐term governmental commitments through the implementation of appropriate policies, the availability of financing, and the creation of markets, among other factors (Dincer 2011). In the near term, strategic investments in research and development, infrastructure, and implementation also would be needed. The rapid expansion of wind energy in many countries provides evidence of such policies contributing to both regional development strategies as well as overarching goals for renewable energy production (Fig. P4).

Figure P3 Wind turbines on Ascension Island, an isolated space‐command and air‐force site in the South Atlantic midway between Africa and South America.

Lance Chung/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

Figure P4 Recharging a Renault EV minivan for local delivery service in Aarhus, Denmark. A scene that is increasingly common around the world.

References

- Aber, J.S., Aber, S.W. and Pavri, F. 2015. Windscapes: A global perspective on wind power. Multi‐Science Publishing, UK, p. 245.

- Brundtland, G.H. 1987. Our common future. World commission on environment and development. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development....

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.12.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Physik / Astronomie |

| ISBN-10 | 1-394-21289-5 / 1394212895 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-394-21289-7 / 9781394212897 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 23,5 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich