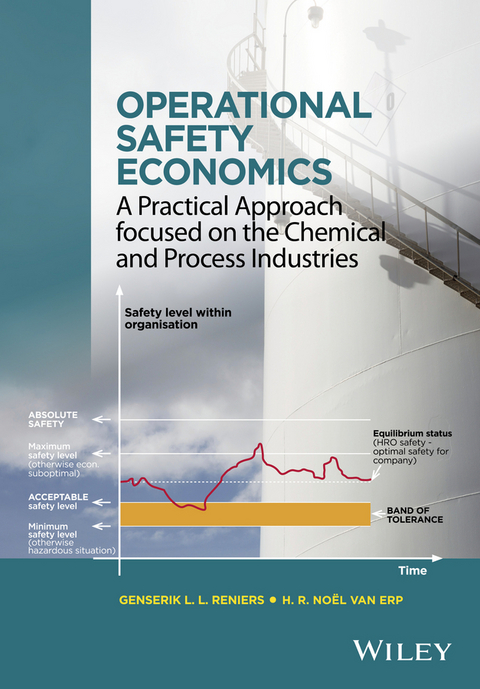

Operational Safety Economics (eBook)

Describes how to make economic decisions regading safety in the chemical and process industries

- Covers both technical risk assessment and economic aspects of safety decision-making

- Suitable for both academic researchers and practitioners in industry

- Addresses cost-benefit analysis for safety investments

Describes how to make economic decisions regading safety in the chemical and process industries Covers both technical risk assessment and economic aspects of safety decision-making Suitable for both academic researchers and practitioners in industry Addresses cost-benefit analysis for safety investments

Genserik Reniers is Professor at the TU Delft (Safety Science Group, Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, The Netherlands), Professor at the HUB campus of the KULeuven (CEDON, Faculty of Economics and Management, Belgium) and at the University of Antwerp (ARGoSS, Faculty of Applied Economic Sciences, Belgium). He received his PhD in Applied Economic Sciences from the University of Antwerp, after completing a Master's degree in Chemical Engineering at the Vrije Universiteit Brussels. His main research interests concern the collaboration and interaction between safety and security topics and socio-economic optimization within the chemical industry. Genserik has authored, co-authored, edited or co-edited more than 20 books in the field of safety and/or security in the process industries, and he is Receiving editor for the Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries (JLPPI), and Associate Editor of Safety Science, two very well-known academic journals in the research field. He has taught safety and security economics (as part of larger courses) since 2006 both at the University of Antwerp and at the HUB-campus of the KULeuven.

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 The “Why” of Operational Safety

In this book, safety within organizations, or safety linked with the operations of an organization (i.e., goods, services, installations, equipment, employees, and so on), is termed “operational safety.” The term “operational safety,” instead of “organizational safety,” is employed to make it very clear that there is a distinction between, for instance, operational organizational safety, and finance-related organizational safety, health-related organizational safety, or public safety. Operational safety, for example, includes making strategic decisions on safety, or using tactical tools to deal with safety. The term “operational” merely indicates the relationship with the operations (all operations) of an organization, nothing more, nothing less.

Operational safety, or the lack thereof, is the result of a series of choices, great and small, within organizations. These choices are extremely complex and depend on a variety of factors within every organization. Important factors are legislation, available technology, socioeconomic aspects, ethical considerations, to name a few. Trade-offs often need to be made and, importantly, a diversity of assumptions need to be made and agreed upon within an organization prior to the safety-related choices. Uncertainties are involved and preferences may differ hugely between people making the decisions. Nevertheless, the goal is always the same: avoid losses! The idea is that by avoiding losses, non-tangible (because hypothetical) gains are realized. Gains can obviously be very small as well as very high, depending on the avoided losses. Determining the avoided losses quantitatively is often not simple, and qualitative aspects sometimes need to be considered when doing so. The ideas and mental models about how to achieve the end objective (i.e., to avoid losses) can thus be quite different, but the goal itself remains the same. In any case, operational safety is thus very much related to the fields of economics, management, and business, and it is therefore very important to be able to grasp and assess the prevention costs together with the level of avoided losses, preferences of decision-makers, assumptions to be made in relation to certain economic models, moral aspects of safety, and so on.

The father of industrial safety, H.W. Heinrich, in his seminal book Industrial Accident Prevention, the first edition published in 1931, starts the book by explaining why operational safety (and accident prevention) is important for company management and why he is in favor of a more scientific approach to this important phenomenon with substantial business impact. He does so by giving an example of a conversation at a conference involving the CEO, the production manager, the treasurer, and the insurance manager of a large manufacturing company. The first five and a half pages of the book are devoted to them talking about money and how they would be able to cut a huge amount of their costs simply by being safer [1]. Remember, this is a time when safety was really in its infancy and the job/function of “safety manager” simply did not exist. Safety management in those days was a synonym to insurance management. Nonetheless, the direct and obvious reason for adding more importance to operational safety in any organization was clear, even in that era, at the very beginning of industrial safety: economic considerations and the profitability of a company.

Things have changed dramatically with respect to the “how” question of operational safety – the safety regulations and procedures, prevention management, techniques and technology available, and so on. However, things have stayed exactly the same regarding the “why” question of operational safety, the answer being to avoid losses to be more profitable as an organization and to be able to “stay in business.” Of course, the benefits for people and society are also very welcome. Nonetheless, for example, in the seminal work by Lees on Loss Prevention in the Process Industries [2, 3], a book of over 3600 print pages on process safety and loss prevention in the chemical and process industries, only a mere 20 pages cover the topic of “economics and insurance.” The literature in other industries is similarly lacking.

It is thus remarkable to note that economic issues have been important from the beginning of industrial safety, but the focus has been on technology (e.g., new risk assessment techniques and innovative ways of prevention), organizational issues (e.g., compliance, new procedures and safety management systems) and, most recently, psychological/sociological human factors issues (e.g., leadership, training and collaboration within groups, safety climate and culture). However, all these advancements should be linked, in some way, to economic assessments. At the end of the day, safety choices are made to be profitable (in some way, not necessarily according to a strict interpretation of the term), not “just to be safe.” This assumes adequate economic assessments within an organization.

There have been attempts to bring more economics into the operational safety decision-making process, but these have not (or hardly) been successful. The reason for their limited success is that they focus on one aspect of economic assessment (e.g., a cost-benefit analysis) but fail to develop the “big picture” of operational safety economics, where all aspects are considered by an integrated economic assessment. Moreover, most economic attempts have focused on macroeconomic issues and have tried to depict operational safety within a macro environment. Such a macroeconomic picture and theory are not interesting or applicable to concrete and microeconomic industrial practice and operational safety decision-making.

Furthermore, even in the present era there is still too much unproductive competition between “objective” and “subjective” as labels to attach to beta science and technology activities on the one hand, and social science activities on the other. However, one should recognize that people, in essence, only wish to distinguish between what is experimentally reproducible within certain limits of uncertainty, and what is either unknown or unpredictable. Looking at the objective–subjective debate in this way leads to the insight that the difference between exact sciences and social sciences is actually rather small, as some risk calculations (of so-called type II risks – see Chapter 2) as well as their rational assessment (using the best risk assessment techniques available to date) are not experimentally reproducible within certain limits of uncertainty. Hence, it is not a question of “or”, but rather one of “and”: the use of “objective” and “subjective” as pejorative terms is counter-productive, and risk experts should understand that risks need to be considered by all kinds of disciplines to improve the decision-process. These disciplines then need to work together based on, among other things, technological, economic, and moral aspects to inform the decision process.

1.2 Back to the Future: the Economics of Operational Safety

One theory proposes that the word “risk” is derived from the Greek word “riza,” which means, amongst others, “cliff” [4]. In Ancient Greece, most transactions were done via shipping. If a ship sank after running into a cliff, it was lost. For an individual shipowner this was obviously a disaster, but a number of shipowners agreed that the possible misfortune should be shared among them, and that an individual shipowner should be compensated for his lost ship by the joint budget of the shipowners. In this way, the future became less uncertain for individual shipowners due to an increased confidence in doing business. This ancient version of insurance is possibly the root cause of the propensity to take risks, and the willingness to loan more for commercial undertakings, as a result of an increased confidence in the future. Hence, risk has, since its origins, been linked with economics.

Furthermore, as Bernstein put it [5], probability theory seems to be a subject made to order for the Ancient Greeks, given their zest for gambling, their skill as mathematicians, their mastery of logic, and their obsession with proof. Yet, although the Greeks were the most civilized of all the ancients, they never ventured into that fascinating world. Only in the Renaissance period, some thousands of years later in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, were the laws of probability conceptualized and developed in contemporary Europe. All the great scientists of this era were in some way involved in the development of probability theory. Gambling and insurance were the fields in which the laws of probability were derived, and where they were used and applied.

A new insight into risk science came in 1738 with the St. Petersburg paper [6]. The author was Daniel Bernoulli, from the famous family of mathematicians. From the late 1600s to the late 1700s, eight Bernoullis had been recognized as celebrated mathematicians. The founding father of this remarkable tribe was Nicolaus Bernoulli of Basel, a wealthy merchant whose Protestant forebears had fled from Catholic-dominated Antwerp, nowadays Belgium, around 1585. The St. Petersburg paper is truly important on the subject of risk as well as on human behavior, because it establishes that people ascribe...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.8.2016 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Chemie ► Technische Chemie |

| Technik | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Bayesian Decision Theory • Business & Management in Chemistry • Chemical and Process Industry • chemical engineering • Chemie • Chemische Verfahrenstechnik • Chemistry • Cost-Benefit Analysis • cost-effectiveness analysis • Ethical Aspects of Safety • Industrial Chemistry • Industrielle Chemie • Loss Aversion • Micro-Economics and Safety • Operational Safety Economics • Process Safety • Prospect Theory • Prozesssicherheit • Technische u. Industrielle Chemie • Wirtschaft • Wirtschaft u. Management in der Chemischen Industrie |

| ISBN-13 | 9781118871515 / 9781118871515 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich