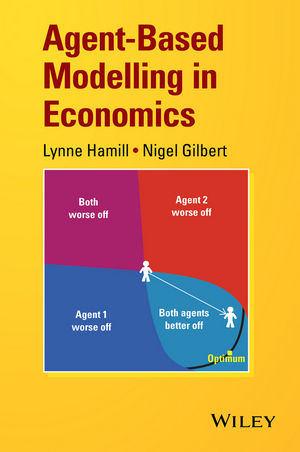

Agent-Based Modelling in Economics (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-94550-6 (ISBN)

Agent-based modelling in economics

Lynne Hamill and Nigel Gilbert, Centre for Research in Social Simulation (CRESS), University of Surrey, UK

New methods of economic modelling have been sought as a result of the global economic downturn in 2008.This unique book highlights the benefits of an agent-based modelling (ABM) approach. It demonstrates how ABM can easily handle complexity: heterogeneous people, households and firms interacting dynamically. Unlike traditional methods, ABM does not require people or firms to optimise or economic systems to reach equilibrium. ABM offers a way to link micro foundations directly to the macro situation.

Key features:

- Introduces the concept of agent-based modelling and shows how it differs from existing approaches.

- Provides a theoretical and methodological rationale for using ABM in economics, along with practical advice on how to design and create the models.

- Each chapter starts with a short summary of the relevant economic theory and then shows how to apply ABM.

- Explores both topics covered in basic economics textbooks and current important policy themes; unemployment, exchange rates, banking and environmental issues.

- Describes the models in pseudocode, enabling the reader to develop programs in their chosen language.

- Supported by a website featuring the NetLogo models described in the book.

Agent-based Modelling in Economics provides students and researchers with the skills to design, implement, and analyze agent-based models. Third year undergraduate, master and doctoral students, faculty and professional economists will find this book an invaluable resource.

Nigel Gilbert, Professor of Sociology and Director of CRESS, University of Surrey, UK.

Lynne Hamill, Centre of Research in Social Simulation (CRESS), University of Surrey, UK.

Agent-based modelling in economics Lynne Hamill and Nigel Gilbert, Centre for Research in Social Simulation (CRESS), University of Surrey, UK New methods of economic modelling have been sought as a result of the global economic downturn in 2008.This unique book highlights the benefits of an agent-based modelling (ABM) approach. It demonstrates how ABM can easily handle complexity: heterogeneous people, households and firms interacting dynamically. Unlike traditional methods, ABM does not require people or firms to optimise or economic systems to reach equilibrium. ABM offers a way to link micro foundations directly to the macro situation. Key features: Introduces the concept of agent-based modelling and shows how it differs from existing approaches. Provides a theoretical and methodological rationale for using ABM in economics, along with practical advice on how to design and create the models. Each chapter starts with a short summary of the relevant economic theory and then shows how to apply ABM. Explores both topics covered in basic economics textbooks and current important policy themes; unemployment, exchange rates, banking and environmental issues. Describes the models in pseudocode, enabling the reader to develop programs in their chosen language. Supported by a website featuring the NetLogo models described in the book. Agent-based Modelling in Economics provides students and researchers with the skills to design, implement, and analyze agent-based models. Third year undergraduate, master and doctoral students, faculty and professional economists will find this book an invaluable resource.

Nigel Gilbert, Professor of Sociology and Director of CRESS, University of Surrey, UK. Lynne Hamill, Centre of Research in Social Simulation (CRESS), University of Surrey, UK.

Preface viii

Copyright notices ix

1 Why agent?]based modelling is useful for economists 1

1.1 Introduction 1

1.2 A very brief history of economic modelling 1

1.3 What is ABM? 4

1.4 The three themes of this book 5

1.5 Details of chapters 6

References 9

2 Starting agent?-based modelling 11

2.1 Introduction 11

2.2 A simple market: the basic model 12

2.3 The basic framework 13

2.4 Enhancing the basic model: adding prices 18

2.5 Enhancing the model: selecting traders 21

2.6 Final enhancement: more economically rational agents 23

2.7 Running experiments 25

2.8 Discussion 26

Appendix 2.A The example model: full version 27

References 28

3 Heterogeneous demand 29

3.1 Introduction 29

3.2 Modelling basic consumer demand theory 30

3.3 Practical demand modelling 39

3.4 Discussion 43

Appendix 3.A How to do it 46

References 52

4 Social demand 53

4.1 Introduction 53

4.2 Social networks 53

4.3 Threshold models 56

4.4 Adoption of innovative products 62

4.5 Case study: household adoption of fixed?-line phones in Britain 64

4.6 Discussion 70

Appendix 4.A How to do it 70

References 78

5 Benefits of barter 80

5.1 Introduction 80

5.2 One?-to?-one barter 81

5.3 Red Cross parcels 88

5.4 Discussion 96

Appendix 5.A How to do it 97

References 104

6 The market 105

6.1 Introduction 105

6.2 Cournot-Nash model 105

6.3 Market model 108

6.4 Digital world model 117

6.5 Discussion 124

Appendix 6.A How to do it 125

References 131

7 Labour market 132

7.1 Introduction 132

7.2 A simple labour market model 142

7.3 Discussion 151

Appendix 7.A How to do it 155

References 161

8 International trade 163

8.1 Introduction 163

8.2 Models 172

8.3 Discussion 183

Appendix 8.A How to do it 185

References 187

9 Banking 189

9.1 Introduction 189

9.2 The banking model 198

9.3 Discussion 206

Appendix 9.A How to do it 209

References 212

10 Tragedy of the commons 214

10.1 Introduction 214

10.2 Model 218

10.3 Discussion 225

Appendix 10.A How to do it 228

References 232

11 Summary and conclusions 234

11.1 Introduction 234

11.2 The models 234

11.3 What makes a good model? 237

11.4 Pros and cons of ABM 238

References 239

Index 242

1

Why agent-based modelling is useful for economists

1.1 Introduction

This book provides an introduction to the power of using agent-based modelling (ABM) in economics. (ABM is sometimes referred to as multi-agent modelling and, in the context of economics, agent-based computational economics (ACE)). It takes some of the usual topics covered in undergraduate economics and demonstrates how ABM can complement more traditional approaches to economic modelling and better link the micro and the macro.

This chapter starts with a brief review of the history of economic modelling to set the context. There follows an outline of ABM: how it works and its strengths. Finally, we set out the plan for the rest of the book.

1.2 A very brief history of economic modelling

The Method I take to do this, is not yet very usual; for instead of using only comparative and superlative Words, and intellectual Arguments, I have taken the course (as a Specimen of the Political Arithmetick I have long aimed at) to express my self in Terms of Number, Weight, or Measure; to use only Arguments of Sense, and to consider only such Causes, as have visible Foundations in Nature.

Sir William Petty (1690)

Whether Sir William Petty was the first economic modeller is arguable. Was Quesnay’s Tableau Economique dated 1767 the first macroeconomic model? Or Ricardo’s 1821 model of a farm the first microeconomic model? (Those interested in these early models should read Morgan, 2012, pp.3–8.) Nevertheless, books of political economy such as Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) or Marshall’s Principles of Economics (1920) had no modelling or mathematics. There is almost none in Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936).

Traditional macroeconomic models

For our purposes, we shall start with the macroeconomic models produced in the 1930s by Frisch and Tinbergen (Morgan, 2012, p.10). These models comprised a set of equations relying on correlations between time series generated from the national accounts. There was no formal link between these macroeconomic models and microeconomic analysis despite the traditional view that ‘the laws of the aggregate depend of course upon the laws applying to individual cases’ (Jevons, 1888, Chapter 3, para 20). Not all saw benefit in these new models. For example, Hayek (1931, p.5) wrote:

…neither aggregates nor averages do act upon each other, and it will never be possible to establish necessary connections of cause and effect between them as we can between individual phenomena, individual prices, etc. I would even go as far as to assert that, from the very nature of economic theory, averages can never form a link in its reasoning.

Nevertheless, macroeconomics became identified as separate field from microeconomics with the publication of Samuelson’s Economics in 1948 (Colander, 2006, p.52).

Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models

The separation of macro- and microeconomics continued until the economic crisis of the mid-1970s prompted what is now known as the Lucas critique. In essence, Lucas (1976) pointed out that policy changes would change the way people behaved and thus the structure being modelled, and this meant that existing models could not be used to evaluate policy. The result was dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models that attempt ‘to integrate macroeconomics with microeconomics by providing microeconomic foundations for macroeconomics’ (Wickens, 2008, p.xiii). This integration is achieved by including ‘a single individual who produces a good that can either be consumed or invested to increase future output and consumption’ (Wickens, 2008, p.2). They are known as either the Ramsey (1928 and 1927) models or as the representative agent models. In effect, the representative agent represents an average person. And this average person bases their decision on optimisation. The limitations of using representative agents have been long recognised (e.g. by Kirman, 1992). But they have continued to be used because they make the analysis more tractable (Wickens, 2008, p.10). However, this is changing. Wickens noted in 2008 (2008, p.10) that ‘more advanced treatments of macroeconomic problems often allow for heterogeneity’, and the technical problems of using heterogeneous agents in DSGE models are now (in 2014) being addressed in cutting-edge research projects.

Complexity economics

Not all economists think that the DSGE models are the right way to proceed. For example, in 2006, Colander published Post Walrasian Macroeconomics: Beyond the Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium Model, a collection of papers that set out the agenda for an alternative approach to macroeconomics that did not make the restrictive assumptions found in DSGE models and in particular did not assume that people operated in an information-rich environment.

The DSGE approach assumes that the economy is capable of reaching and sustaining an equilibrium, although there is much debate about how equilibrium is defined. Others take the view that the economy is a non-linear, complex dynamic system which rarely, if ever, reaches equilibrium (see, e.g. Arthur, 2014). While in a linear system, macro level activity amounts to a simple adding up of the micro actions, in a non-linear system, something new may emerge. Arthur (1999) concluded:

After two centuries of studying equilibria – static patterns that call for no further behavioral adjustments – economists are beginning to study the general emergence of structures and the unfolding of patterns in the economy. When viewed in out-of-equilibrium formation, economic patterns sometimes simplify into the simple static equilibria of standard economics. More often they are ever changing, showing perpetually novel behavior and emergent phenomena.

Furthermore, ‘Complex dynamical systems full of non-linearities and sundry time lags have been completely beyond the state of the arts until rather recently’, but ‘agent-based simulations make it possible to investigate problems that Marshall and Keynes could only “talk” about’ (Leijonhufvud, 2006). More recently, Stiglitz and Gallegati (2011) have pointed out that use of the representative agent ‘rules out the possibility of the analysis of complex interactions’; and they ‘advocate a bottom-up approach, where high-level (macroeconomic) systems may possess new and different properties than the low-level (microeconomic) systems on which they are based’. ABM is therefore seen by many as offering a way forward.

The impact of the 2008 economic crisis

Once again, it has taken an economic crisis to prompt a re-evaluation of economic modelling. Indeed, the 2008 economic crisis caused a crisis for economics as a discipline. It is now widely recognised that a new direction is needed and that ABM may provide that. Farmer and Foley (2009) argued in Nature that ‘Agent-based models potentially present a way to model the financial economy as a complex system, as Keynes attempted to do, while taking human adaptation and learning into account, as Lucas advocated’. A year later, The Economist (2010) was asking if ABM can do better than ‘conventional’ models. Jean-Claude Trichet (2010), then president of the European Central Bank, spelt out what was needed:

First, we have to think about how to characterise the homo economicus at the heart of any model. The atomistic, optimising agents underlying existing models do not capture behaviour during a crisis period. We need to deal better with heterogeneity across agents and the interaction among those heterogeneous agents. We need to entertain alternative motivations for economic choices. Behavioural economics draws on psychology to explain decisions made in crisis circumstances. Agent-based modelling dispenses with the optimisation assumption and allows for more complex interactions between agents. Such approaches are worthy of our attention.

The Review of the Monetary Policy Committee’s Forecasting Capability for the Bank of England concluded that ‘The financial crisis exposed virtually all major macro models as being woefully ill-equipped to understand the implications of this type of event’ (Stockton, 2012, p.6). In early 2014, the United Kingdom’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) sponsored a conference on Diversity in Macroeconomics, subtitled New Perspectives from Agent-Based Computational, Complexity and Behavioural Economics, to bring together practitioners of the new approaches, mainstream academic economists and policymakers (Markose, 2014).

Furthermore, by 2013, the call for change had spread to the teaching of economics (Economist, 2013), and in 2014, Curriculum Open-Access Resources in Economics (CORE) was launched, providing an interactive online resource for a first course in economics, and it is planned to include agent-based simulations in this new way of teaching economics (CORE, 2014; Royal Economic Society, 2014).

So, what is ABM? We give an overview in the next section.

1.3 What is ABM?

The development of computational social...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.11.2015 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Mathematik / Informatik ► Mathematik ► Statistik |

| Mathematik / Informatik ► Mathematik ► Wahrscheinlichkeit / Kombinatorik | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Empirische Sozialforschung | |

| Technik | |

| Wirtschaft ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Wirtschaft ► Volkswirtschaftslehre | |

| Schlagworte | ABM • agent-based • Complexity • Dynamics • Economics • Economic Theory • Heterogeneity • Interactions • Markets • Micro-Foundations • Modelling • netlogo • Research Methodologies • Sociology • Soziologie • Soziologische Forschungsmethoden • Statistics • Statistics for Social Sciences • Statistik • Statistik in den Sozialwissenschaften • Volkswirtschaftslehre • Wirtschaftstheorie |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-94550-6 / 1118945506 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-94550-6 / 9781118945506 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich