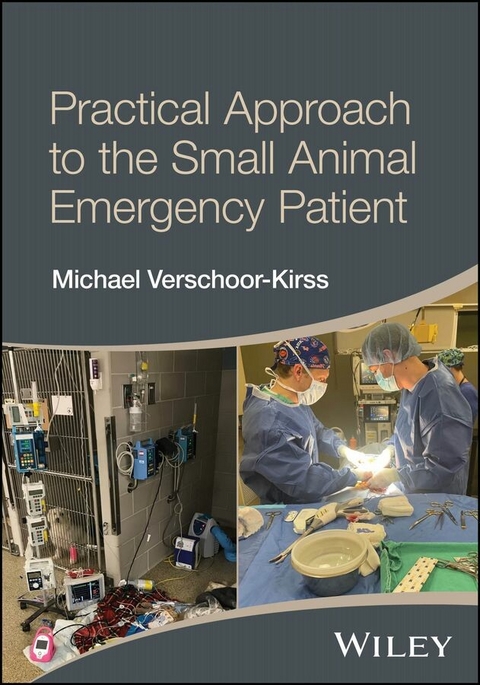

Practical Approach to the Small Animal Emergency Patient (eBook)

630 Seiten

Wiley (Verlag)

978-1-394-33453-7 (ISBN)

A concise, accessible guide to clinical decision making in veterinary emergency medicine focused on the thought process in selecting diagnostic and treatment options

Practical Approach to the Small Animal Emergency Patient helps veterinarians identify the critical questions to identify diagnostic and therapeutic priorities when faced with an emergency situation. The book reviews important decision points for common emergencies and emphasizes how to think, not just what to do.

The first section of the book covers general principles of emergency medicine topics such as triage, sedation and lab work selection, while the latter part of the book applies those principles to common emergency presentations. The intention of this book is not to provide the clinician with an exhaustive review of pathophysiology, but uses current research and decision making tools to provide the clinician with the questions and tools to decide whether a certain intervention is appropriate. Each chapter also includes a section on client communication to help guide new clinicians in speaking with family members about diagnostic testing, treatment approaches, and prognosis.

Written by a board-certified criticalist and practicing veterinarian in emergency medicine, Practical Approach to the Small Animal Emergency Patient includes information on:

- Fluid therapy, covering fluid requirements, fluid selection, patients with heart murmurs, and correcting electrolyte abnormalities

- Sedation and analgesia, covering appropriate use and risks of inadequate or inappropriate sedation

- Diabetic emergencies including diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperglycemic nonketotic syndrome, and hypoglycemia

- Treatment for car accidents, penetrating trauma, and dog bite wounds

- Gastrointestinal distress, covering surgical versus non-surgical causes, the need for imaging, and difference between inpatient and outpatient assessment

Practical Approach to the Small Animal Emergency Patient is an essential guide for clinicians, particularly new graduates and emergency doctors, seeking to gain confidence and improve their decision-making in emergency situations.

Michael Verschoor-Kirss, DVM, DACVECC, is Staff Criticalist at VCA South Shore Animal Hospital in South Weymouth, Massachusetts, USA.

A concise, accessible guide to clinical decision making in veterinary emergency medicine focused on the thought process in selecting diagnostic and treatment options Practical Approach to the Small Animal Emergency Patient helps veterinarians identify the critical questions to identify diagnostic and therapeutic priorities when faced with an emergency situation. The book reviews important decision points for common emergencies and emphasizes how to think, not just what to do. The first section of the book covers general principles of emergency medicine topics such as triage, sedation and lab work selection, while the latter part of the book applies those principles to common emergency presentations. The intention of this book is not to provide the clinician with an exhaustive review of pathophysiology, but uses current research and decision making tools to provide the clinician with the questions and tools to decide whether a certain intervention is appropriate. Each chapter also includes a section on client communication to help guide new clinicians in speaking with family members about diagnostic testing, treatment approaches, and prognosis. Written by a board-certified criticalist and practicing veterinarian in emergency medicine, Practical Approach to the Small Animal Emergency Patient includes information on: Fluid therapy, covering fluid requirements, fluid selection, patients with heart murmurs, and correcting electrolyte abnormalitiesSedation and analgesia, covering appropriate use and risks of inadequate or inappropriate sedationDiabetic emergencies including diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperglycemic nonketotic syndrome, and hypoglycemiaTreatment for car accidents, penetrating trauma, and dog bite woundsGastrointestinal distress, covering surgical versus non-surgical causes, the need for imaging, and difference between inpatient and outpatient assessment Practical Approach to the Small Animal Emergency Patient is an essential guide for clinicians, particularly new graduates and emergency doctors, seeking to gain confidence and improve their decision-making in emergency situations.

CHAPTER 1

The Triage Exam

Critical questions

- Could this pet have a life-threatening illness or injury based on its signalment and presenting complaint?

- Is this pet in shock?

- Are they having difficulty breathing?

INTRODUCTION

The triage exam starts when you, a technician, assistant, or receptionist, first interact with a pet and owner in the hospital. It is a combination of the presenting complaint, physical exam, and point of care lab work/imaging that you acquire prior to speaking with the owner. The goal of the triage exam is to detect and diagnose life-threatening issues that would lead to patient morbidity and mortality without immediate intervention. However, your triage exam is also helpful in guiding the first conversation with a pet owner because it can give you an idea as to how sick a pet is and what initial diagnostics and treatments may be necessary.

THE TRIAGE HISTORY

The triage history is never complete, and you’re frequently receiving it secondhand. While occasionally a pet owner can quickly give you a definitive diagnosis (i.e. “my pet was just hit by a car”), many times the presenting complaint is vaguer, such as “he/she’s just really lethargic.” Therefore, it is important for both you and your staff to effectively detect the presenting complaints that may require emergent intervention.

Important questions to consider for pets who may benefit from a triage physical exam and/or emergent diagnostic testing:

- Can the pet walk?

The inability to ambulate will include many cardiovascularly unstable, intoxicated, and neurologically impaired animals. Pets with this presenting complaint should be immediately assessed using the triage physical exam (see below) to evaluate for shock and stability. Pets who have a history of “collapse” should similarly be evaluated, EVEN if they are currently walking. We will talk more specifically about the approach to the “down” pet and gurney patient in a later chapter.

- Is the pet having difficulty breathing?

Difficulty breathing can indicate upper airway obstruction, pulmonary pathology, pleural space disease, and metabolic instability. All pets with difficulty breathing should be evaluated using the triage physical exam, as the inability to appropriately ventilate and oxygenate can rapidly spiral and progress to cardiac arrest.

- Can the pet urinate?

This is most important in male cats, whose presenting complaint can widely vary when experiencing a urethral obstruction. Since this condition can trigger life-threatening sequelae, including cardiac arrest, it should always be confirmed or denied via either triage imaging or physical exam.

- Does the pet have concerning comorbidities?

Most owners will share if their pet has previously diagnosed chronic diseases but differentiating those that could be life-threatening (i.e. congestive heart failure [CHF]) and those that are less concerning (i.e. Lyme disease) can be challenging. While many patients presenting complaints are typically related to their chronic disease or medication, as we’ll discuss later, you cannot always assume the two are related.

- Does the patient have a history of seizures? If so, how many?

Many first-time seizure patients (as long as they have only had one) do not require emergent intervention. However, if a patient has had cluster seizures (>2 seizures in 24 hours) or if the seizure is believed to be the result of a toxic ingestion, they should be evaluated emergently. Furthermore, patients having seizures in the waiting room or with the owner (even though non-life-threatening) tend to increase the overall anxiety level and may make discussing diagnostics and treatments more challenging. Further information about seizure management can be found in Chapter 16.

- Has the pet ingested anything foreign or toxic, and if so, when?

Quickly assessing these pets may allow you to induce emesis that can either allow for rapid discharge in the case of an ingested foreign body or reduce the absorbed dose of a toxin. See also Chapter 20 for further information on the management of the toxic ingestion.

- Is there any history of recent or acute abdominal distention? These cases should be immediately evaluated using the triage exam to rule out cavitary effusions or gastric dilatation/volvulus (GDV).

THE TRIAGE PHYSICAL EXAM

Your evaluation on triage is NOT a complete physical exam. The presence of abnormalities, such as flank alopecia and dental disease, is less critical than determining cardiovascular stability.

The goals of the triage physical exam are to:

- Identify signs of shock with the intent of guiding diagnostics to understand the underlying cause for shock.

- Identify a suspected cause for respiratory distress (if any) to help with early intervention.

- Identify other underlying disease processes (i.e. urinary obstruction) that would require further diagnostics and immediate intervention.

The first 30 seconds of the triage exam are geared at answering the following questions:

- Is my patient alive?

- Does my patient have a patent airway and functioning respiratory system?

- Is my patient in shock?

Question 1

Is my patient alive?

While many patients (especially cats) can present apparently moribund, there are several disease processes, such as urinary obstruction and decompensated shock, that can be rapidly reversed with appropriate treatment. Your initial assessment should involve visualization of any spontaneous respiratory efforts and either pulse palpation, cardiac auscultation, or palpation of the apex beat of the heart, which is especially helpful in cats. If there is any doubt as to these findings within 30 seconds, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be immediately initiated. Further information on CPR can be found in Chapter 24.

Question 2

Is the airway intact and are the lungs functional?

We’ll delve deeper into assessment of respiratory distress in a later chapter, but there are a couple of key points to make here. Broadly, respiratory distress can be divided into an upper and lower component. While upper respiratory/airway disease can be more rapidly fatal (i.e. brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome [BOAS] crisis), lower airway disease in the long term carries a poorer prognosis. Either way, correct identification and treatment for either localization is critical for effective stabilization. Therefore, consider the following questions:

- Do I hear audible (without a stethoscope) respiratory noise? This is more commonly associated with upper respiratory diseases such as laryngeal paralysis, BOAS, or a nasopharyngeal polyp (among others).

- Is the patient using accessory muscles to breathe, orthopneic, agonal, or have cyanotic mucous membranes? Regardless of etiology, these signs are representative of imminent respiratory arrest, and endotracheal intubation should be initiated.

- Is the signalment and history consistent with CHF, asthma, pleural effusion, pneumonia, laryngeal paralysis, tracheal collapse, or BOAS? These seven differential diagnoses represent the most common emergency presentations for true (nontraumatic) respiratory distress. There are usually both signalment and physical exam clues that can help rule in or rule out certain diseases on this list, though we’ll discuss these further in Chapter 15.

- Have I done point of care ultrasound (POCUS)? This is ALWAYS an indicated test for pets in respiratory distress, as it can begin differentiating between cardiac, pulmonary, and noncardiopulmonary causes for dyspnea.

Further details on the management of the dyspneic patient can be found in Chapter 15.

Question 3

Is my patient in shock?

Appropriate identification of shock and its underlying etiology is crucial for the rapid stabilization of any sick patient. Physical exam findings of shock can include pale mucous membranes, abnormal heart rate (high or low), dull mentation, reluctance to walk, and poor pulse quality. In cats, a low temperature is highly correlated with both sepsis and mortality (Pontiero et al. 2025). A high shock index (heart rate divided by blood pressure) is a more sensitive indicator of shock in both dogs and cats (Porter et al. 2013, Fadel et al. 2025) but requires measurement of a systolic blood pressure, which may not be immediately available. POCUS is useful for identifying cavitary effusions that are frequently a source of shock, and in skilled hands, it can also be helpful in evaluating for a cardiogenic source of shock. Furthermore, even in many seemingly stable older patients, it is not uncommon to find significant abnormalities on POCUS.

MISCELLANEOUS PRESENTING COMPLAINTS

- Is this a urethral obstruction? Every male cat presenting with vague or poorly differentiated signs should have its bladder palpated to rule out a urethral obstruction. See also Chapter 13.

- Is this pet mentally appropriate? While dull mentation can be a sign of shock/systemic illness, in cases of seizures or central nervous system disease, being prepared for additional seizures through placement of an IV catheter is helpful for treating any additional events. See also Chapter 16.

- Is there any history of acute abdominal distention? Evaluating these pets via POCUS is helpful in rapidly ruling in/out peritoneal effusion as well as stratifying the risk of GDV.

- Has the pet...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.10.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Veterinärmedizin |

| Schlagworte | down dog • veterinary assessment • veterinary diabetes • veterinary diagnostics • Veterinary Diseases • veterinary er • veterinary fluid therapy • Veterinary Monitoring • veterinary sedation • veterinary trauma |

| ISBN-10 | 1-394-33453-2 / 1394334532 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-394-33453-7 / 9781394334537 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich