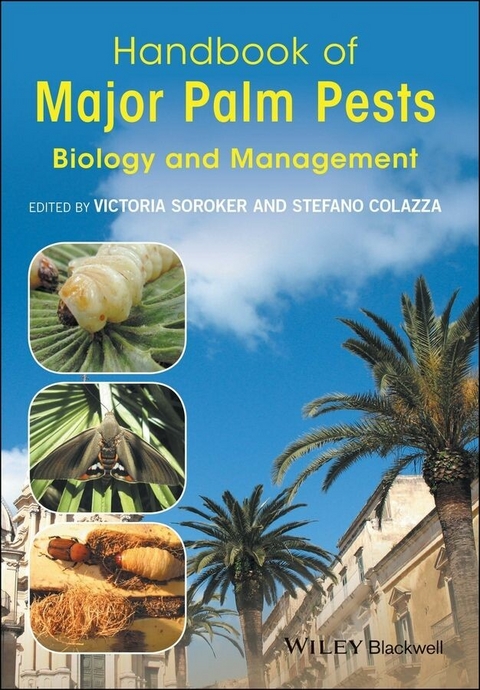

Handbook of Major Palm Pests (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-119-05748-2 (ISBN)

An essential compendium for anyone working with or studying palms, it is dedicated to the detection, eradication, and containment of these invasive species, which threaten the health and very existence of global palm crops.

Handbook of Major Palm Pests: Biology and Management contains the most comprehensive and up-to-date information on the red palm weevil and the palm borer moth, two newly emergent invasive palm pests which are adversely affecting palm trees around the world. It provides state-of-the-art scientific information on the ecology, biology, and management of palm pests from a global group of experts in the field.An essential compendium for anyone working with or studying palms, it is dedicated to the detection, eradication, and containment of these invasive species, which threaten the health and very existence of global palm crops.

Victoria Soroker is Senior Researcher in the Department of Entomology at Agricultural Research Organization, The Volcani Center, Israel and a lecturer at Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Her work over 30 years involves both basic aspects of insect physiology, chemical ecology and behavior of several insects and mites as well as applied research towards development of integrated pest management practices. For the last 16 years much of her research efforts have focused around finding solution for detection and control of the date palm pest and especially red palm weevil. Over the years she has mentored graduate students and published widely in peer-reviewed journals. Currently she serves as a president of the Entomological Society of Israel. Stefano Colazza is Professor at the Department of Agricultural and Forest Sciences at the University of Palermo, Italy. He is a specialist in infochemicals and behavioral ecology of plant, insect, herbivores and insect parasitoid interactions, with a special interest in the chemical ecology of plant volatile organic compounds in a tri-trophic context. He has been involved in these research areas for over 30 years and his work has been published widely in peer-reviewed journals. He is the co-editor of Chemical Ecology of Insect Parasitoids (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

Introduction

Neil Audsley1, Victoria Soroker2 and Stefano Colazza3

1Fera Science Ltd, Sand Hutton, York, United Kingdom

2Department of Entomology, Agricultural Research Organization, The Volcani Center, Israel

3Department of Agricultural and Forest Sciences, University of Palermo, Italy

Invasive Alien Species

The EU commission's definition of an invasive alien species is “an animal or plant that is introduced accidentally or deliberately into a natural environment where they are not normally found, with serious negative consequences for their new environment” (European Commission 2016). Alien species occur in all major taxonomic groups and are found in every type of habitat. The EU-funded project DAISIE (Delivering Alien Invasive Species Inventories for Europe) reported that over 12,000 alien species are present in Europe and 10–15% of them are considered invasive (DAISIE 2016). The globalization of travel and trade and the expansion of the human population have facilitated the movement of species, especially in Europe, where travel is unrestricted between most member states.

The ingress, establishment, and spread of alien pest species are of high importance because their impacts are wide ranging. As well as reducing yields from agriculture, horticulture, and forestry, they can cause the displacement or extinction of native species, cause habitat loss, affect biodiversity, disrupt ecosystem services, and pose a threat to animal and human health.

The risks posed to the EU region by non-native species are widely recognized and have led to legislation to combat their threat, the most recent of which (Regulation (EU) No. 1143/2014) came into force on January 1, 2015 (European Commission 2016). This regulation aims to minimize or mitigate the adverse effects of invasive alien species. It also supports preceding directives on invasive alien species (European Commission 2016). This directive highlights anticipated interventions to combat invasive alien species, including prevention, early warning, rapid response, and management. Despite this regulation, it can be assumed that the introduction of new invasive alien species into Europe will continue, and the spread of those species that have become established is likely to continue as well. Climate change may well make it easier for some species to become established in Europe, hence the risks posed by the invasive alien species are likely to increase.

Huge costs are associated with invasive species; in the USA, damage has been estimated at more than €100 billion a year, with insects contributing around 10% of this damage (Pimentel, Zuniga, and Morrison 2005). In Europe, damage exceeds €12 billion annually, but this is most likely an underestimate because, for many alien species in Europe, the potential economic and environmental impacts are still unknown (European Environment Agency 2012). It is clear that failure to deal with invasive species in a timely and efficient manner can be extremely costly. The DAISIE project has produced fact sheets of the worst 100 of these species (http://www.europe-aliens.org/speciesTheWorst.do), which include insects such as the Mediterranean fruit fly Ceratitis capitata and the Western corn rootworm Diabrotica virgifera, describing their economic, social, and environmental impacts.

Failure to detect and eradicate pest populations at some point prior to, during, or following transportation facilitates the introduction, spread, and establishment of invasive alien pests. This is exemplified by the establishment of the RPW and PBM in and around the Mediterranean basin.

R. ferrugineus and P. archon: Invasive Pests of Palm Trees

Palm trees in the Mediterranean basin and elsewhere are under serious threat from the RPW and PBM, two invasive species that were accidentally introduced through the import of infested palms. The larvae of both of these insects bore into palm trees and feed on the succulent plant material stem and/or leaves. The resulting damage remains invisible long after infestation, and by the time the first symptoms of the attack appear, they are so serious that, in the case of the RPW, they often result in the death of the tree (Ferry and Gómez 1998; Faleiro 2006; EPPO Reporting Service 2008a; Dembilio and Jaques 2015).

The PBM, native to South America, was first reported in Europe—in France and Spain—in 2001, but it is believed to have been introduced before 1995 on palms imported from Argentina. It has since spread to other EU member states (Italy, Greece, and Cyprus) with isolated reports in the UK, Bulgaria, Denmark, Slovenia, and Switzerland (Vassarmidaki, Thymakis, and Kontodimas 2006; EPPO Reporting Service 2008b, 2010; Larsen 2009; Vassiliou et al. 2009). Although P. archon has not been reported to be a significant pest in South America, with the exception of reports from Buenos Aires (Sarto i Monteys and Aguilar 2005), it has been the cause of serious damage and plant mortalities, mainly in ornamental palm nurseries, in France, Italy, and Spain (Riolo et al. 2004; Vassarmidaki Thymakis, and Kontodimas 2006). It may also increase the risk of RPW spread by creating primary damage to palms, which then attracts the weevil.

The RPW is native to southern Asia and Melanesia (Ferry and Gómez 1998; EPPO Reporting Service 2008a), but is now spreading worldwide. After becoming a major pest in the Middle Eastern region in the mid-1980s (Abraham, Koya, and Kurian 1989), it was introduced into Spain in the mid-1990s (Barranco, de la Peña, and Cabello, 1996) and rapidly spread around the Mediterranean basin to areas where susceptible palm trees are grown outdoors (EPPO Reporting Service 2008a and b). Its range now also includes much of Asia, regions of Oceania and North Africa, the Caribbean, and North America (EPPO Reporting Service 2008a–2009; Pest Alert 2010). Of the EU member states, Italy and Spain are the worst affected, accounting for around 90% of the total number of outbreaks reported, but the RPW is also prevalent in France (DRAAF-PACA 2010).

The high rate of spread of the RPW in Europe following its introduction is most likely due to a combination of factors that resulted in inadequate eradication and containment of this weevil. The lack of effective early-detection methods, the continued import of infested palms, and the transportation of palms and offshoots from contaminated to non-infested areas have had a major impact (Jacas 2010).

By 2007, the spread of the RPW had become uncontrollable, resulting in the adoption of emergency measures to prevent its further introduction and spread within the community (Commission decision 2007/365/EC 2007). These measures included restricted import and movement of susceptible palms and annual surveys for RPW. However, although the interceptions of infested material decreased, the procedures to prevent spread were not fully effective.

In 2010, new recommendations on methods for the control, containment, and eradication of RPW were made by a Commission Expert Working Group and at the International Conference on Red Palm Weevil Control Strategy for Europe, held in Valencia, Spain. They recognized that:

- in most areas, eradication of RPW was unlikely to be achieved so containment would be more appropriate;

- better enforcement of EU legislation for intra-community trade and imports from third countries was required to prevent the further spread of the RPW within EU member states;

- there was a need for research and development of programs focused on the early detection, control, and eradication of RPW.

A successful program for RPW eradication was undertaken in the Canary Islands to protect the native Phoenix canariensis after this insect was detected in the resorts of Fuerteventura and Gran Canaria in 2005. This included a ban on the importation of any palms from outside the Islands and a program of work that included monitoring for the pest, inspection of palms and nurseries, accreditations for transplantation and movement of palms, elimination of infected palms, plant health treatments, and mass trapping, and an awareness campaign that included a website, talks, seminars, courses, newsletters, and leaflets. In 2007, an outbreak was reported on Tenerife, but since 2008 no additional weevils have been detected (Giblin-Davis 2013; Gobcan 2009).

The key aspects of protective measures against the RPW and PBM (and other invasive pests) are:

- to rapidly and accurately detect these insects in imported palms, or palms being moved between different areas;

- to rapidly detect new infested areas;

- to take appropriate measures to eradicate the pests;

- where eradication is unlikely, i.e. in areas where these pests are already established, take appropriate action to contain and control the pests within that area to prevent further spread within the community.

However, the threats posed by the RPW and PBM are now greater than ever because:

- one or both of these pests is already present in almost all countries around the Mediterranean basin where susceptible palms are grown;

- previous measures have proven insufficient and often ineffective;

- eradication in “uncontrolled” areas, such as private gardens, is difficult;

- re-infestation of “clean” areas can occur due to a single untreated palm tree;

- infestations in some rural areas may go undetected;

- import of palms from third countries, which themselves have RPW and/or PBM infestations, continues;

- climate...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.1.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Botanik |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Zoologie | |

| Technik | |

| Veterinärmedizin | |

| Weitere Fachgebiete ► Land- / Forstwirtschaft / Fischerei | |

| Schlagworte | Agriculture • Ãkologie / Pflanzen • beaudoinollivier • Biowissenschaften • Conclusion • contributors • crown • defoliators • Ecological • Entomologie • Entomology • Europe • feeders • fronds • Landwirtschaft • leaves • Life Sciences • Morphology • Nomenclature • Ökologie / Pflanzen • Palm • Palmen • Palms • Pests • Pests, Diseases & Weeds • Pflanzenkrankheit • Physiology • plant ecology • References • representative • Rhynchophorus ferrugineus • SAP • Schädlinge, Krankheiten u. Unkräuter • Schädlinge, Krankheiten u. Unkräuter • Trees |

| ISBN-10 | 1-119-05748-5 / 1119057485 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-119-05748-2 / 9781119057482 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich