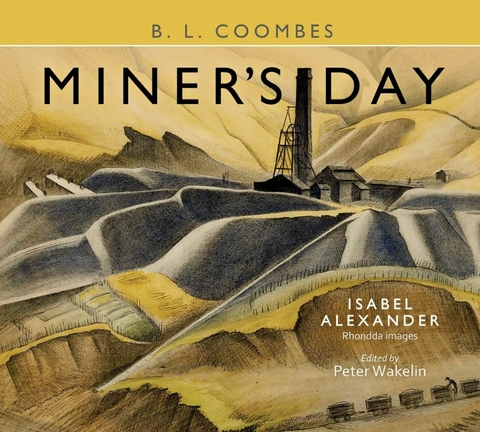

Miner's Day (eBook)

144 Seiten

Parthian Books (Verlag)

978-1-913640-86-6 (ISBN)

Bertie Louis Coombes, or B. L. Coombes (1893-1974), was a Welsh coalminer, notable for his autobiography These Poor Hands: The Autobiography of a Miner in South Wales (1939) which became an instant bestseller. He also produced short stories, dramas and other autobiographical works about the lives of coalminers and the communities in which they lived.

Miner's Day is a testament to coal mining communities in the mid-twentieth century. First published by Penguin Books as a slim paperback in 1945, it married a reflective text by Britain's outstanding miner-writer, B. L. Coombes, to illustrations by the artist Isabel Alexander. The original text is now republished in a generous new format with a substantial introduction and the full wealth of images that Isabel Alexander made in an extended project to document people and places in the South Wales coalfield a unique addition to the visual representation of mining communities. Bert Coombes in words and Isabel Alexander in images each aimed to reveal the layered reality of coal-mining communities to a distant public. They documented both work below ground and devastated environments above. They described the lives not just of working men but women, children and older people too. They saw poverty and despair but also love, hope and even humour. The South Wales they captured echoes similar communities across the world and evolving global challenges to health, work and environment. Miner's Day is as relevant now as it was in 1945.

CHAPTER ONE

A chilled darkness had followed the March evening. Two sounds disturbed the night when I crossed the slope towards my work, forcing the left side of each boot into the ground to prevent my slipping. High above, a heavy plane moved through the night sky with a stuttering drone, while so close that the ground seemed to be always quivering I heard the ceaseless pant, pant, pant of the huge compressor engines which were gulping in the sweet mountain air and forcing it through pipes into the colliery working, so that many engines there, as well as the conveyors and coal-cutters, would have power to do their work.

Men were flying through strange surroundings high above me, and I knew that down below my feet, in that underground world where I would soon be, other men were working in unnatural conditions so that life in our country could go on. In the valley the mining villages were invisible; conquered by the blackout. Buses snarled or whined as they brought miners from distant areas to their work. Sometimes a torch stabbed the darkness for a bright moment, then faded, but that instant of light pulled my sight round and made me lose my exact sense of direction. The staccato warning of a whistle preceded the rumbling of a workmen’s train, already easing its speed because it was nearing the station. The steam came up to shroud me whilst I walked, making me think of washing day at home with the boiler bubbling over the fire. Benjy and Steve and Dave would be on that train with a couple of hundred more mates of mine. Five minutes later, when I was quite near the colliery premises, another train roared in, bringing some hundreds of miners from another area. Hermit and George, with the others, would be sitting on those bare dusty seats. Probably they would be bringing something with them. A puppy, or cabbage plants, or a book, or perhaps a newspaper cutting; for there is a constant interchange of things which actually interest us.

My mates were coming from all directions, like an army of invaders who had surrounded their objective, towards that hole in the ground. In one more hour they would have met and greeted their mates from the afternoon shift, and those men would be homeward bound by train, or bus, or on foot if they lived close. Such is our regular cycle as day follows day and shift meets shift with its continual use of man’s energy and skill to rob these mountains of their treasure.

To us it was just another start after a weekend of resting. The return to a job which we have done so many times that we do not notice its strangeness … yet that is not quite correct. We always sense the change both in conditions and surroundings, even in our breathing and thinking. During the weekend our mole-like existence fades from close consciousness, but is revived when we start again in that pit life which is our second nature. When we have cleared our throats and washed the grime from our bodies we feel so different; as a good dinner drives away the hollowness of hunger. That is the queerest part of it all—how swiftly we forget the problems of the pit; possibly because they are so far hidden from daylight. I have to stir my memory: ‘What was the work we did at the end of last Friday’s shift?’ or, ‘Where did I last leave my tools?’ Then we get back amongst it, and we adapt ourselves to a continual bend and watchfulness. Were I twelve months away from mining I know that the dust of underground workings would be as remote to me as the bogey fears of childhood. I know it; that way it has been with so many.

E. L., the Overman, Blaencwm, 1944, lithograph, 39 × 32

The caption to this portrait in ‘Coal: The National Plague Spot’, 1946, said: ‘E. L. is an overman – a sort of foreman or manager’s deputy. He started work at 11 and has been at it for 53 years. His group gets the worst of both worlds – the men tend to think of it as on the owners’ side, yet the wages are little above a collier’s. E. L., however, is well-liked – the men find him firm but fair.’ Isabel noted that he worked at Blaencwm but she based the background on her drawings at Gilfach Goch.

Meanwhile I am in it every day. In some ways repelled by what I see and feel, yet in other aspects enjoying the battle with the inside of the mountain; but most especially happy to be a good comrade for most of these men who are moving alongside me now. We are black figures moving through a black night towards a black pit.

About halfway up that tram incline, where we stumble over iron rollers and hook our toes under steel ropes, or bang into a loaded coal tram, we meet the last of the afternoon men on his way down. He has found his pipe and smokes a pleasant-smelling tobacco. He greets each shadowy group with a ‘Good evening, boys.’ Always I return the greeting after the others, so that I shall again hear his reply. His voice is deep and clear, with a sound of culture in it. His greeting and the aroma of his smoking linger with us while we stumble along, like the last reminder of a comfortable world.

After we have sidled past the rows of trams, walked through the bank of steam which is the panting breath of the pit engines, hidden our smokes for the morning, and exchanged our number checks for a lamp, we go underground. The weather affects our speed in this direction. When it is wet or cold we hurry inside, glad of the earth’s shelter, but on those nights, when the moon shows high and clear in the sky, we linger to extend and savour those last moments, looking upwards and thinking what such a night must mean to the lives and romances of others. Then, slowly, we move inwards before the threat of an oil lamp carried by the overman.

Inside the entrance the refuge holes are crowded by youngsters, averaging about twenty years of age. They are always disputing, viciously it seems. Their language is brutally profane. Girls, film stars, miners’ agents, politicians, are all brought inside that bawling discussion and are cast out besmirched as they pass on to condemn others of whom their knowledge and conception must be very slight. Everything and everybody outside their group receives the same verdict of being, profanely and emphatically, ‘no blasted good.’ They are just a section of our mining youth, not the largest section by any count, but their insolence and indifference to all discipline make them a problem in our work and our future. They linger until the overman has almost reached them, then move inwards unwillingly, disputing and swearing as they go. The overman follows, knowing they will only go so far and so fast as he makes them. What mistake in environment and education has brought these young lads into this condition?

Above us steel arches support the roof like the ribs inside a giant whale. Our lamps reflect on the water which flows blackly outwards along the slimy gutters. The long underground roadway is clustered with the lights of walking men—who seem to be hundreds of shadows which talk to one another about what news the radio gave last or the papers misrepresented: for the disbelief of what they saw in the papers seems unanimous.

I overtake two men, both elderly and named David. One is slight and short, the other quite the reverse. Before each shift they meet, greeting one another with ‘Hallo. You’ve come?’ Then, on the walk to the colliery, and through that two-mile underground journey they go on together without exchanging one word. After the shift is ended they wait at an inside cabin, assure each other they have come again and resume that wordless journey homewards. In the canteen they take strict turn to fetch the two cups of tea and sit silently next to one another until their train is due in. Possibly both can see their life and their usefulness passing away and feel comfort from this company of another man who is similarly placed.

Far inside we pass under a large engine which is built above the mine roadway so that trams can run underneath. The man who drives this engine is deeply religious and therefore a butt for the thoughtless amongst the youngsters … and many of the adults. I respect him, without following his teachings, because he fights to keep his convictions under difficult conditions. My feeling is that the mining world is surely the stoniest soil on which the seed of religion has ever been sown. Many of our workers feel there is something inhuman about a man who does not blaspheme at his work, although in their outside lives they act as decent folk. Even in the dread surroundings of a bad accident I have never heard a prayer offered or suggested. But to return to that engine driver.

He is a lay preacher and likes to prepare his sermons. Last week I was coming in late after explaining some trouble to the overman; one of my jobs is as a miners’ committeeman. All under the earth was so still as I hurried along under that engine when suddenly a strong voice proclaimed from high above me in the darkness: ‘Unless ye repent of your sins ye shall surely perish.’ Not being at all prepared, nor knowing which sin was meant, I jumped upwards and forwards rapidly and my heart did a lot of fluttering until I realised it was the engine driver doing a bit of rehearsing when he thought no one was within hearing. Another time, walking a yard behind my mate at this spot, a fairly large stone dropped from the roof twenty feet above and fell between the two of us edgeways, slicing the back of my mate’s coat in its fall. ‘Missus’ll have a jib about mending that,’ he stated, when he examined the rip.

When I talk of stones do not imagine something that you can...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.7.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Technik ► Bergbau | |

| Schlagworte | British industry • history of mining • history of South Wales • mining in the twentieth century • mining in Wales • mining memoir • welsh miners |

| ISBN-10 | 1-913640-86-8 / 1913640868 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-913640-86-6 / 9781913640866 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich