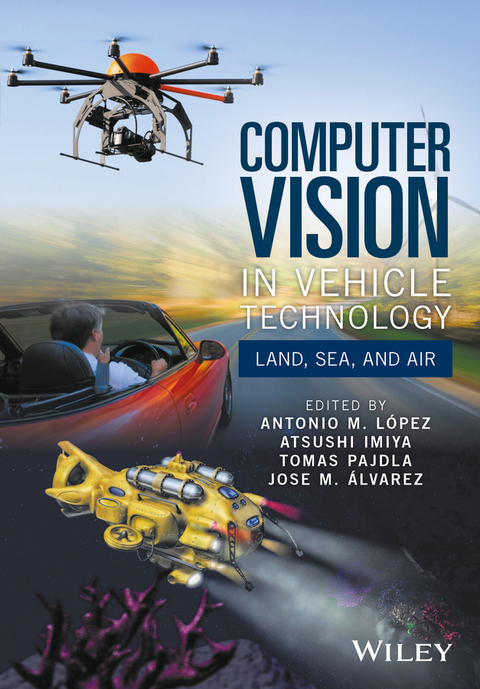

Computer Vision in Vehicle Technology (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-86805-8 (ISBN)

A unified view of the use of computer vision technology for different types of vehicles

Computer Vision in Vehicle Technology focuses on computer vision as on-board technology, bringing together fields of research where computer vision is progressively penetrating: the automotive sector, unmanned aerial and underwater vehicles. It also serves as a reference for researchers of current developments and challenges in areas of the application of computer vision, involving vehicles such as advanced driver assistance (pedestrian detection, lane departure warning, traffic sign recognition), autonomous driving and robot navigation (with visual simultaneous localization and mapping) or unmanned aerial vehicles (obstacle avoidance, landscape classification and mapping, fire risk assessment).

The overall role of computer vision for the navigation of different vehicles, as well as technology to address on-board applications, is analysed.

Key features:

- Presents the latest advances in the field of computer vision and vehicle technologies in a highly informative and understandable way, including the basic mathematics for each problem.

- Provides a comprehensive summary of the state of the art computer vision techniques in vehicles from the navigation and the addressable applications points of view.

- Offers a detailed description of the open challenges and business opportunities for the immediate future in the field of vision based vehicle technologies.

This is essential reading for computer vision researchers, as well as engineers working in vehicle technologies, and students of computer vision.

Dr. Antonio M. López is the head of the Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) Group of the Computer Vision Center (CVC), and Associate Professor of the Computer Science Department, both from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB). Antonio received a BSc degree in Computer Science from the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) and a PhD degree in Computer Vision from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB). In 1996, he participated in the foundation of the CVC at the UAB, where he has held different institutional responsibilities. Antonio is also the responsible of the Software Engineering specialty at the UAB. Moreover, he has been the principal investigator of numerous public and industrial research projects, and is a co-author of more than 100 journal and conference papers, all in the field of computer vision. Antonio's main research interests are vision-based driver assistance and autonomous driving.

Atsushi Imiya is Professor at IMIT, Chiba University. He has served as a PC member of DGCI, IWCIA, and SSVM conferences for many years. He is an editorial member of 'Pattern Recognition (Journal)' and a co-editor of 'Digital and Image Geometry' held at Schloss Dagstuhl in 2000, MLDM2007 (Machine Learning and Data Mining in Pattern Recognition), of which proceedings were published from Springer-Verlag. He is a general co-chair of S+SSPR (Statistical, and Synthetic and Structural Pattern Recognition) 2012. He is participating in a government-funded project titled: 'Computational anatomy for computer-aided diagnosis and therapy: Frontiers of medical image sciences' as an applied mathematician. He also serves as a review committee of the research projects internationally.

Dr. Tomas Pajdla is an Assistant Professor and Distinguished Senior Researcher at the Czech Technical University in Prague. He works in geometry and algebra of computer vision and robotics with the emphasis on geometry a calibration of camera systems, 3D reconstruction and industrial vision. Dr. Pajdla published more than 75 works in journals and proceedings and received awards for his work; OAGM 1998, 2012, BMVC 2002, ICCV 2005 and ACCV 2014. He has served as a program co-chair of ECCV 2004 and ECCV 2014, and regularly as area chair of ICCV, CVPR, ECCV, ACCV, ICRA and BMVC. He is a member of the ECCV Board, and served on the boards of IEEE PAMI, Computer Vision and Image Understanding and IPSJ Transactions on Computer Vision and Applications journals. Dr. Pajdla has connections to the planetary research community through EU projects with NASA, ESA and EADS Astrium and to automotive industry via Daimler AG.

Jose M. Alvarez is currently a researcher at NICTA and a research fellow at the Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. Previously, he was a postdoctoral researcher at the Computational and Biological Learning Group at New York University with Professor Yann LeCun. During his Ph.D. he was a visiting researcher at the University of Amsterdam and Volkswagen AG research. His main research interests include deep learning and data driven methods for dynamic scene understanding.

A unified view of the use of computer vision technology for different types of vehicles Computer Vision in Vehicle Technology focuses on computer vision as on-board technology, bringing together fields of research where computer vision is progressively penetrating: the automotive sector, unmanned aerial and underwater vehicles. It also serves as a reference for researchers of current developments and challenges in areas of the application of computer vision, involving vehicles such as advanced driver assistance (pedestrian detection, lane departure warning, traffic sign recognition), autonomous driving and robot navigation (with visual simultaneous localization and mapping) or unmanned aerial vehicles (obstacle avoidance, landscape classification and mapping, fire risk assessment). The overall role of computer vision for the navigation of different vehicles, as well as technology to address on-board applications, is analysed. Key features: Presents the latest advances in the field of computer vision and vehicle technologies in a highly informative and understandable way, including the basic mathematics for each problem. Provides a comprehensive summary of the state of the art computer vision techniques in vehicles from the navigation and the addressable applications points of view. Offers a detailed description of the open challenges and business opportunities for the immediate future in the field of vision based vehicle technologies. This is essential reading for computer vision researchers, as well as engineers working in vehicle technologies, and students of computer vision.

Dr. Antonio M. López is the head of the Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) Group of the Computer Vision Center (CVC), and Associate Professor of the Computer Science Department, both from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB). Antonio received a BSc degree in Computer Science from the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) and a PhD degree in Computer Vision from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB). In 1996, he participated in the foundation of the CVC at the UAB, where he has held different institutional responsibilities. Antonio is also the responsible of the Software Engineering specialty at the UAB. Moreover, he has been the principal investigator of numerous public and industrial research projects, and is a co-author of more than 100 journal and conference papers, all in the field of computer vision. Antonio's main research interests are vision-based driver assistance and autonomous driving. Atsushi Imiya is Professor at IMIT, Chiba University. He has served as a PC member of DGCI, IWCIA, and SSVM conferences for many years. He is an editorial member of "Pattern Recognition (Journal)" and a co-editor of "Digital and Image Geometry" held at Schloss Dagstuhl in 2000, MLDM2007 (Machine Learning and Data Mining in Pattern Recognition), of which proceedings were published from Springer-Verlag. He is a general co-chair of S+SSPR (Statistical, and Synthetic and Structural Pattern Recognition) 2012. He is participating in a government-funded project titled: "Computational anatomy for computer-aided diagnosis and therapy: Frontiers of medical image sciences" as an applied mathematician. He also serves as a review committee of the research projects internationally. Dr. Tomas Pajdla is an Assistant Professor and Distinguished Senior Researcher at the Czech Technical University in Prague. He works in geometry and algebra of computer vision and robotics with the emphasis on geometry a calibration of camera systems, 3D reconstruction and industrial vision. Dr. Pajdla published more than 75 works in journals and proceedings and received awards for his work; OAGM 1998, 2012, BMVC 2002, ICCV 2005 and ACCV 2014. He has served as a program co-chair of ECCV 2004 and ECCV 2014, and regularly as area chair of ICCV, CVPR, ECCV, ACCV, ICRA and BMVC. He is a member of the ECCV Board, and served on the boards of IEEE PAMI, Computer Vision and Image Understanding and IPSJ Transactions on Computer Vision and Applications journals. Dr. Pajdla has connections to the planetary research community through EU projects with NASA, ESA and EADS Astrium and to automotive industry via Daimler AG. Jose M. Alvarez is currently a researcher at NICTA and a research fellow at the Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. Previously, he was a postdoctoral researcher at the Computational and Biological Learning Group at New York University with Professor Yann LeCun. During his Ph.D. he was a visiting researcher at the University of Amsterdam and Volkswagen AG research. His main research interests include deep learning and data driven methods for dynamic scene understanding.

Chapter 1

Computer Vision in Vehicles

Reinhard Klette

School of Engineering, Computer and Mathematical Sciences, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

This chapter is a brief introduction to academic aspects of computer vision in vehicles. It briefly summarizes basic notation and definitions used in computer vision. The chapter discusses a few visual tasks as of relevance for vehicle control and environment understanding.

1.1 Adaptive Computer Vision for Vehicles

Computer vision designs solutions for understanding the real world by using cameras. See Rosenfeld (1969), Horn (1986), Hartley and Zisserman (2003), or Klette (2014) for examples of monographs or textbooks on computer vision.

Computer vision operates today in vehicles including cars, trucks, airplanes, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) such as multi-copters (see Figure 1.1 for a quadcopter), satellites, or even autonomous driving rovers on the Moon or Mars.

Figure 1.1 (a) Quadcopter. (b) Corners detected from a flying quadcopter using a modified FAST feature detector.

Courtesy of Konstantin Schauwecker

In our context, the ego-vehicle is that vehicle where the computer vision system operates in; ego-motion describes the ego-vehicle's motion in the real world.

1.1.1 Applications

Computer vision solutions are today in use in manned vehicles for improved safety or comfort, in autonomous vehicles (e.g., robots) for supporting motion or action control, and also for misusing UAVs for killing people remotely. The UAV technology has also good potentials for helping to save lives, to create three-dimensional (3D) models of the environment, and so forth. Underwater robots and unmanned sea-surface vehicles are further important applications of vision-augmented vehicles.

1.1.2 Traffic Safety and Comfort

Traffic safety is a dominant application area for computer vision in vehicles. Currently, about 1.24 million people die annually worldwide due to traffic accidents (WHO 2013), this is, on average, 2.4 people die per minute in traffic accidents. How does this compare to the numbers Western politicians are using for obtaining support for their “war on terrorism?” Computer vision can play a major role in solving the true real-world problems (see Figure 1.2). Traffic-accident fatalities can be reduced by controlling traffic flow (e.g., by triggering automated warning signals at pedestrian crossings or intersections with bicycle lanes) using stationary cameras, or by having cameras installed in vehicles (e.g., for detecting safe distances and adjusting speed accordingly, or by detecting obstacles and constraining trajectories).

Figure 1.2 The 10 leading causes of death in the world. Chart provided online by the World Health Organization (WHO). Road injury ranked number 9 in 2011

Computer vision is also introduced into modern cars for improving driving comfort. Surveillance of blind spots, automated distance control, or compensation of unevenness of the road are just three examples for a wide spectrum of opportunities provided by computer vision for enhancing driving comfort.

1.1.3 Strengths of (Computer) Vision

Computer vision is an important component of intelligent systems for vehicle control (e.g., in modern cars, or in robots). The Mars rovers “Curiosity” and “Opportunity” operate based on computer vision; “Opportunity” has already operated on Mars for more than ten years. The visual system of human beings provides a proof of existence that vision alone can deliver nearly all of the information required for steering a vehicle. Computer vision aims at creating comparable automated solutions for vehicles, enabling them to navigate safely in the real world. Additionally, computer vision can also work constantly “at the same level of attention,” applying the same rules or programs; a human is not able to do so due to becoming tired or distracted.

A human applies accumulated knowledge and experience (e.g., supporting intuition), and it is a challenging task to embed a computer vision solution into a system able to have, for example, intuition. Computer vision offers many more opportunities for future developments in a vehicle context.

1.1.4 Generic and Specific Tasks

There are generic visual tasks such as calculating distance or motion, measuring brightness, or detecting corners in an image (see Figure 1.1b). In contrast, there are specific visual tasks such as detecting a pedestrian, understanding ego-motion, or calculating the free space a vehicle may move in safely in the next few seconds. The borderline between generic and specific tasks is not well defined.

Solutions for generic tasks typically aim at creating one self-contained module for potential integration into a complex computer vision system. But there is no general-purpose corner detector and also no general-purpose stereo matcher. Adaptation to given circumstances appears to be the general way for an optimized use of given modules for generic tasks.

Solutions for specific tasks are typically structured into multiple modules that interact in a complex system.

Example 1.1.1 Specific Tasks in the Context of Visual Lane Analysis

Shin et al. (2014) review visual lane analysis for driver-assistance systems or autonomous driving. In this context, the authors discuss specific tasks such as “the combination of visual lane analysis with driver monitoring..., with ego-motion analysis..., with location analysis..., with vehicle detection..., or with navigation....” They illustrate the latter example by an application shown in Figure 1.3: lane detection and road sign reading, the analysis of GPS data and electronic maps (e-maps), and two-dimensional (2D) visualization are combined into a real-view navigation system (Choi et al. 2010).

Figure 1.3 Two screenshots for real-view navigation.

Courtesy of the authors of Choi et al. (2010)

1.1.5 Multi-module Solutions

Designing a multi-module solution for a given task does not need to be more difficult than designing a single-module solution. In fact, finding solutions for some single modules (e.g., for motion analysis) can be very challenging. Designing a multi-module solution requires:

- 1. that modular solutions are available and known,

- 2. tools for evaluating those solutions in dependency of a given situation (or scenario; see Klette et al. (2011) for a discussion of scenarios) for being able to select (or adapt) solutions,

- 3. conceptual thinking for designing and controlling an appropriate multi-module system,

- 4. a system optimization including a more extensive testing on various scenarios than for a single module (due to the increase in combinatorial complexity of multi-module interactions), and

- 5. multiple modules require control (e.g., when many designers separately insert processors for controlling various operations in a vehicle, no control engineer should be surprised if the vehicle becomes unstable).

1.1.6 Accuracy, Precision, and Robustness

Solutions can be characterized as being accurate, precise, or robust. Accuracy means a systematic closeness to the true values for a given scenario. Precision also considers the occurrence of random errors; a precise solution should lead to about the same results under comparable conditions. Robustness means approximate correctness for a set of scenarios that includes particularly challenging ones: in such cases, it would be appropriate to specify the defining scenarios accurately, for example, by using video descriptors (Briassouli and Kompatsiaris 2010) or data measures (Suaste et al. 2013). Ideally, robustness should address any possible scenario in the real world for a given task.

1.1.7 Comparative Performance Evaluation

An efficient way for a comparative performance analysis of solutions for one task is by having different authors testing their own programs on identical benchmark data. But we not only need to evaluate the programs, we also need to evaluate the benchmark data used (Haeusler and Klette 2010 2012) for identifying their challenges or relevance.

Benchmarks need to come with measures for quantifying performance such that we can compare accuracy on individual data or robustness across a diversity of different input data.

Figure 1.4 illustrates two possible ways for generating benchmarks, one by using computer graphics for rendering sequences with accurately known ground truth,1 and the other one by using high-end sensors (in the illustrated case, ground truth is provided by the use of a laser range-finder).2

Figure 1.4 Examples of benchmark data available for a comparative analysis of computer vision algorithms for motion and distance calculations. (a) Image from a synthetic sequence provided on EISATS with accurate ground truth. (b) Image of a real-world sequence provided on KITTI with approximate ground truth

But those evaluations need to be considered with care since everything is not comparable. Evaluations depend on the benchmark data used; having a few summarizing numbers may not be really of relevance for particular scenarios possibly occurring in the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.2.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Informatik ► Theorie / Studium ► Künstliche Intelligenz / Robotik |

| Technik ► Elektrotechnik / Energietechnik | |

| Technik ► Fahrzeugbau / Schiffbau | |

| Schlagworte | Autonomous Driving • autonomous navigation • Bild- u. Videoverarbeitung • computer vision • Electrical & Electronics Engineering • Elektrotechnik u. Elektronik • Fahrzeugtechnik • Image and Video Processing • Maschinelles Sehen • Micro Aerial Vehicle (MAV) • On-board vision systems • Robotics • Robotik • Rover • Seafloor Rovers • Underwater Imaging • unmanned aerial vehicle • Vision-based Driver Assistance Systems |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-86805-6 / 1118868056 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-86805-8 / 9781118868058 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich