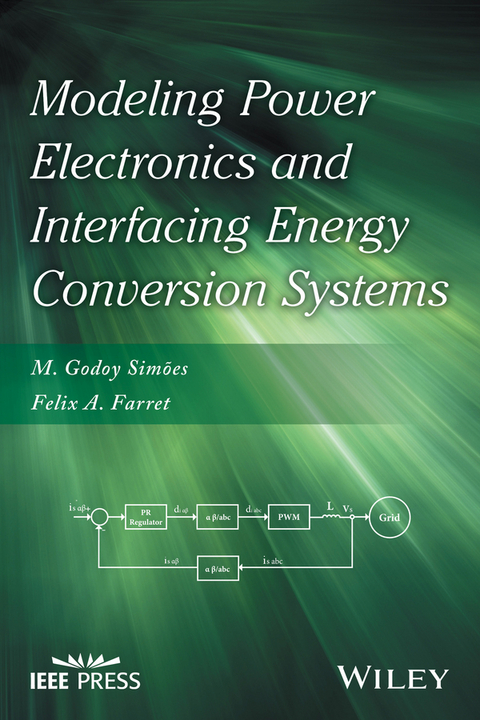

Modeling Power Electronics and Interfacing Energy Conversion Systems (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-119-05847-2 (ISBN)

Discusses the application of mathematical and engineering tools for modeling, simulation and control oriented for energy systems, power electronics and renewable energy

This book builds on the background knowledge of electrical circuits, control of dc/dc converters and inverters, energy conversion and power electronics. The book shows readers how to apply computational methods for multi-domain simulation of energy systems and power electronics engineering problems. Each chapter has a brief introduction on the theoretical background, a description of the problems to be solved, and objectives to be achieved. Block diagrams, electrical circuits, mathematical analysis or computer code are covered. Each chapter concludes with discussions on what should be learned, suggestions for further studies and even some experimental work.

- Discusses the mathematical formulation of system equations for energy systems and power electronics aiming state-space and circuit oriented simulations

- Studies the interactions between MATLAB® and Simulink® models and functions with real-world implementation using microprocessors and microcontrollers

- Presents numerical integration techniques, transfer-function modeling, harmonic analysis and power quality performance assessment

- Examines existing software such as, MATLAB®/Simulink®, Power Systems Toolbox and PSIM to simulate power electronic circuits including the use of renewable energy sources such as wind and solar sources

The simulation files are available for readers who register with the Google Group: power-electronics-interfacing-energy-conversion-systems@googlegroups.com. After your registration you will receive information in how to access the simulation files, the Google Group can also be used to communicate with other registered readers of this book.

M. Godoy Simões is the director of the Center for Advanced Control of Energy and Power Systems (ACEPS) at Colorado School of Mines. He was an US Fulbright Fellow for Aalborg University, Institute of Energy Technology (Denmark). He is IEEE Fellow, with the citation: 'for applications of artificial intelligence in control of power electronics systems.' Dr. Simões is a pioneer to apply neural networks and fuzzy logic in power electronics, motor drives and renewable energy systems. He is co-author of the book Integration of Alternative Sources of Energy (Wiley 2006), now in the second edition.

Felix A. Farret is co-author of the book Integration of Alternative Sources of Energy (Wiley 2006, now in the second edition). Currently he is a Professor in the Department of Processing Energy, Federal University of Santa Maria, Brazil. Since 1974, he has taught undergraduate and graduate courses and has been conducting research and development in industrial electronics and alternative energy sources.Marcelo Godoy Simões is the director of the Center for Advanced Control of Energy and Power Systems (ACEPS) at Colorado School of Mines. He was an US Fulbright Fellow for Aalborg University, Institute of Energy Technology (Denmark). He is IEEE Fellow, with the citation: "for applications of artificial intelligence in control of power electronics systems." Dr. Simões is a pioneer to apply neural networks and fuzzy logic in power electronics, motor drives and renewable energy systems. He is co-author of the book Integration of Alternative Sources of Energy (Wiley 2006), now in the second edition. Felix A. Farret is co-author of the book Integration of Alternative Sources of Energy (Wiley 2006, now in the second edition). Currently he is a Professor in the Department of Processing Energy, Federal University of Santa Maria, Brazil. Since 1974, he has taught undergraduate and graduate courses and has been conducting research and development in industrial electronics and alternative energy sources.

1

INTRODUCTION TO ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING SIMULATION

Theoretical modeling‐based analysis is a process where a model is set up based on laws of nature and logic, using mostly mathematics, physics, and engineering—initially with simplified assumptions about their processes and aiming at finding an input/output model. The following basic procedures and formulations are usually used in supporting a theoretical or an experimental model:

- Balance equations, for stored masses, energies, and impulses

- Physical–chemical constitutive equations

- Phenomenological equations of irreversible processes (thermal conductivity, diffusion, chemical reaction)

- Entropy balance equations, if several irreversible processes are interrelated

- Connection equations, describing the interconnection of process elements

Using such formulation principles, a system can be understood in terms of their ordinary differential equations, or their algebraic equations, and then a physical device or a computer simulation or an emulation can be devised in order to obey such equations. The physical system is initialized with their proper initial values, and their development over time mimics the differential equations.

Integrators and function generation can accomplish simulation of an ordinary differential equation (ODE). It has been discussed by Ragazzini in 1947 that the continuous functions of several variables could be approximated by a combination of scalar products, scalar functions, and their time derivatives. We have to find first suitable state variables, i.e. variables that account for energy storage. Typically those variables appear differentiated in the ordinary differential equations.

Several computer‐based simulations depend on the principles of analog computing, where a differential equation such as Equation 1.1 must be represented in terms of fundamental operations such as integration, addition, multiplication, and function generation. The old analog computer circuitry required scaling of variables, but in a modern computer, floating‐point numbers represents the variables and scaling is not required. Higher precision, flexibility for modifications, better stability, reporting facilities, and lower costs are the main advantages of the digital processing. The analog computing may have an advantage for high‐speed online data processing, for example, a voltage across a resistor has immediate response. A function such as the one represented by Equation 1.1 requires several interconnections to represent the required calculations.

Numerical solution techniques and algorithms to solve differential equation are essential and used in digital computers. There are many ways to find approximate numerical solutions to ordinary differential equations such as the one represented by Equation 1.1. The methods are based on replacing the differential equations by a difference equation. Euler’s method is based on the approximation of the derivative by a first‐order difference, but there are more efficient techniques such as Runge–Kutta and multistep methods. These methods were well known when digital simulators emerged in the 1960s, but several contributions made them better and more stable when solving difference approximations, for example, the automatic step length adjustment was a very important contribution. A more mathematical‐oriented model for dynamical systems can be based on differential–algebraic equations (DAEs), that is, a mixture of differential and algebraic equations, such as those represented by Equation 1.2:

It is not always possible to convert such an equation to an ODE because the Jacobian may not be invertible. Numerical methods for DAEs appeared during the 1970s. However, even until today, the algorithms for DAEs are still not so well developed as the ones for ordinary differential equations. Most of the reliable computer simulators and emulators are based on numerical solution of ODES. So, a DAE is mostly a mathematical exploration, and usually the engineering and physics problems are modeled using ODEs.

When a system is formulated based on DAEs, the derivatives are not usually expressed explicitly. In addition, some derivatives of some dependent variables may not appear in the equations. A system of DAEs can be converted to a system of ODEs by differentiating it with respect to the independent variable. The index of a DAE is effectively the number of times you need to differentiate the DAEs to get a system of ODEs. Even though the differentiation is possible, it is not generally used as a computational technique because properties of the original DAEs are often lost in numerical simulations of the differentiated equations.

Suppose a linear system is defined by an algebraic, such as Equation 1.3.

If A is a matrix, a numerical solution has the following possible scenarios:

- , it is a square system, and it can have a unique solution, as long as there are no rows or columns linearly dependent of the other ones. This is usually a numerical problem of matrix inversion. There are interesting input/output mapping of large systems, where A is not known, and experimental data will support the definition of A, for example, with gradient descent methods for system identification.

- , it is an overdetermined (or over identified) system and at least one solution can be defined. Overidentified systems are common in curve fitting to experimental data, and least square methods for minimizing the sum of the data deviation squares from the model are a suitable approach.

- , it is an underdetermined system, and a trivial solution with at most m nonzero components can be defined. Undetermined systems involve more unknowns than equations, so the solution is never unique. There is a particular solution computed by the so‐called QR factorization with a column pivoting method. This kind of problem may have additional constraints, and the methodology becomes the so‐called linear programming.

In this book, we emphasize the applications of ODEs, particularly in their state‐space format, for modeling energy systems and power electronics. We can then study their dynamics and transient solutions, or we can use linear algebraic systems to understand static or steady‐state solutions for such systems. The approach adopted in this book best fits a senior undergraduate or a first‐year graduate course. Differential equation‐based systems are developed and simulated from practical examples that focus typical electrical circuit applications, energy conversion, renewable energy sources, interconnection of distributed generation, power electronics, power systems, and power quality problems. The linearization of systems is discussed based on average modeling and the use of Taylor series expansion. Techniques of Fourier expansion are developed for power quality considerations, including the understanding of the discrete Fourier transform (DFT), fast Fourier transform (FFT), and wavelet techniques. MATLAB® will be used for programming, solving several numerical algorithms, and graph plotting. Simulink® is used for block diagram‐oriented modeling. Electrical circuit‐oriented modeling is analyzed using the Power Systems Toolbox of MATLAB as well as the PSIM circuit simulator.

The analog computing paradigm requires explicit state models and linkage from input towards output. That is a kind of limitation because blocks must have a unidirectional data flow from inputs to outputs, but such paradigm supports the majority of solutions for engineering systems. A consequence is that it is difficult to build physics‐based model libraries in the block diagram languages with bidirectional dataflow or bidirectional energy flow. There are other more advanced paradigms for simulation of multiphysics domain in object‐oriented programming using software for differential–algebraic systems aiming at noncausal modeling with mathematical equations. Such object‐oriented approach facilitates the reuse of modeling knowledge. However, this book is not focused on such advanced hybrid computer simulations. The intention of this book is to support a computer‐based laboratory for power electronics, power systems, distributed generation, and alternative energy, as well as to be a self‐study material for readers with background in electrical power who want to understand how to apply mathematical and engineering tools for modeling, simulation, and control design of energy systems and power electronics. The sequence of chapters follows a progressive complexity, but it is possible to change the order or skip material in order to customize a sequence that best fits a combination of the fundamental topics (power electronics, power systems, distributed generation, and renewable energy). Most of chapters are centered on a laboratory project as an example, but some chapters are more discursive with practical explanations of how to model a diversity of electrical engineering systems.

This book follows the approach of problem‐based learning strategies, with some project‐based learning methodologies. Each chapter has a brief introduction on the theoretical background, a description of the problems to be solved, and objectives to be achieved. Block diagrams, electrical circuits, mathematical analysis, or computer code are also discussed. A solution is presented for the problems or the approach of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.9.2016 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | IEEE Press |

| Wiley - IEEE | Wiley - IEEE |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Technik ► Elektrotechnik / Energietechnik |

| Schlagworte | digital signal processing • Electrical & Electronics Engineering • Electrical circuits • Electrical Engineering • electrical machine modeling • Elektrotechnik u. Elektronik • Energy systems • Instrumentation and Control Interfaces • Leistungselektronik • Materialien f. Energiesysteme • Materials for Energy Systems • Materials Science • Materialwissenschaften • Mesh and Nodal Analysis • Power Electronics • power quality analysis • PSIM Simulation • Systems Design |

| ISBN-10 | 1-119-05847-3 / 1119058473 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-119-05847-2 / 9781119058472 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich