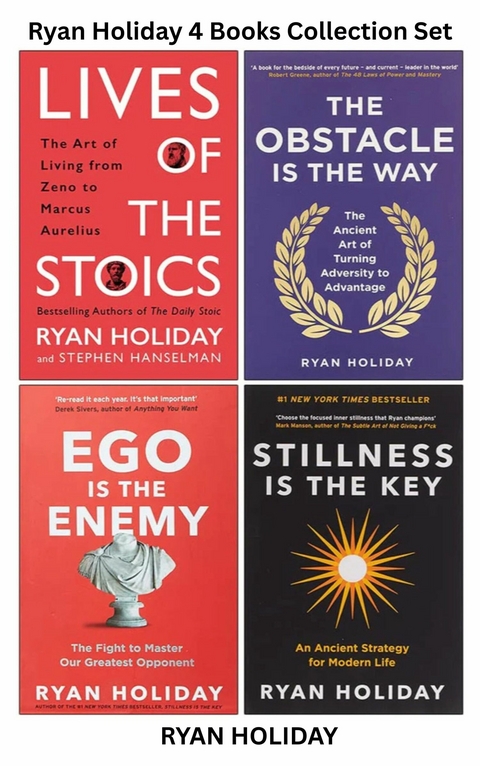

Ryan Holiday 4 Books Collection Set (eBook)

629 Seiten

Publishdrive (Verlag)

978-0-00-105779-1 (ISBN)

Lives of the Stoics :

In this book, Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman offer a fresh approach to understanding Stoicism through the lives of the people who practiced it - from Cicero to Zeno, Cato to Seneca, Diogenes to Marcus Aurelius. Through short biographies of all the famous, and lesser-known, Stoics, this book will show what it means to live stoically, and reveal the lessons to be learned from their struggles and successes.

The Obstacle is the Way:

We give up too easily. With a simple change of attitude, what seem like insurmountable obstacles become once-in-a-lifetime opportunities. Ryan Holiday, who dropped out of college at nineteen to serve as an apprentice to bestselling 'modern Machiavelli' Robert Greene and is now a media consultant for billion-dollar brands, draws on the philosophy of the Stoics.

Ego is the Enemy:

In Ego is the Enemy, Ryan Holiday shows us how and why ego is such a powerful internal opponent to be guarded against at all stages of our careers and lives, and that we can only create our best work when we identify, acknowledge and disarm its dangers.

Stillness is the Key:

Throughout history, there has been one quality that great leaders, makers, artists and fighters have shared. The Zen Buddhists described it as inner peace, the Stoics called it ataraxia and Ryan Holiday calls it stillness: the ability to be steady, focused and calm in a constantly busy world.

BRUTUS

O, name him not! Let us not break with him,

For he will never follow anything

That other men begin.

They feared their friend lacked courage and that his ego would hold them back. History would bear this out. Almost immediately after Caesar’s death, Cicero began to take credit for the other men’s deed, claiming that Brutus had shouted his name as he plunged the dagger in.

As Cicero would explain in a speech, “Now why me in particular? Because I knew? Quite possibly the reason [Brutus] called my name was just this: after an achievement similar to my own he called on me rather than another to witness that he was now my rival in glory.”

What’s past is prologue, Shakespeare would say, and so it was with his own life. His need for fame, his tendency to shift with the wind, would dog him to the end. In Caesar’s wake rose young Octavian and Mark Antony. Cicero would again choose the wrong side and, conspicuously, decline to serve in the civil war he helped bring about.

Cicero’s final work, surprisingly, would be on duty. He had never been a man whose career was about duty. Fame. Honor. Proving doubters wrong. That had been his drive. But with his twenty-one-year-old son, Marcus, just completing his first year of philosophical training in Athens, perhaps Cicero wished to instill in his boy a stronger sense of moral purpose than his own ambitious father had in himself. The work premises that Marcus, like Hercules at the crossroads, is being wooed by vice and at risk of forsaking the path of virtue. In response, Cicero took up the Stoic efforts of Diogenes, Antipater, Panaetius (above all), and Posidonius to not only lay down Stoic ethical theory, but give his wayward son the practical precepts he needed to keep him off the road to ruin.

In the work’s dedication, he wrote to Marcus:

Although philosophy offers many problems, both important and useful, that have been fully and carefully discussed by philosophers, those teachings which have been handed down on the subject of moral duties seem to have the widest practical application. For no phase of life, whether public or private, whether in business or in the home, whether one is working on what concerns oneself alone or dealing with another, can be without its moral duty; on the discharge of such duties depends all that is morally right, and on their neglect all that is morally wrong in life.

They are words well written, as was nearly everything Cicero produced. What was missing, it seems, is any personal absorption of them.

In the end, it would be Cicero’s love of rhetoric that would seal his personal fate. He had chided Rutilius Rufus for his brevity in the face of his accusers, saying that rhetoric might have saved him. But walking the plank in 44–43 BC, Cicero delivered fourteen orations against Mark Antony, one of the heirs to Caesar’s power.

It would be one thing if Cicero had, as Cato would have, simply condemned excess and brutality where he saw it. Instead, his Philippics, as the speeches are now known, were a political ploy to play Mark Antony off Octavian, Caesar’s nephew, both with equally authoritarian designs. Cicero was splitting the difference, not standing on principle. And considering his grandiose comparison of his own speeches to those made by Demosthenes more than two hundred years earlier, it’s clear that once again he was motivated more by the limelight than by truth.

The remarks were his undoing. Caesar, though a tyrant, had always shown leniency and good humor—and love for the art of rhetoric. Mark Antony possessed no such gentleness. The Second Triumvirate debated Cicero’s fate for several days, and then, deprived of a trial—as he had deprived his enemies so many years before—the sentence was in: death.

He tried to flee. Then wavered and returned. He contemplated a dramatic suicide like Cato and, shuddering at doing anything so final, struggled on.

Cicero had long talked a big game. He had written about duty; he had admired the great men of history. He had accomplished so much in his life. He had accumulated mansions and honors. He had been to all the right schools. He had held all the right jobs. He had made his name so famous that no one would ever care about his lowly origins again. He was not just a new man, he was, for a period, the man.

But he had compromised much to get there. He had ignored the sterner parts of Stoicism—the parts about self-discipline and moderation (as his chubby visage demonstrates), the duties and the obligations. He had ignored his conscience, in defiance of the oracle, to seek out the cheers of the crowd. If he had followed Posidonius and Zeno better, his life might not have turned out differently, but he would have been steadier. He would have been stronger.

Now, when it counted, there was nothing in him, nothing in his fair-weather personal philosophy that could have helped him stand up in this moment where cruel fate was bearing down on him. He could not rely on the inner citadel that countless Stoics had when they faced death, because he had not built it when he had the chance.

All Cicero could do was hope for mercy.

It did not come. Exhausted, like an animal that’s been chased, he gave up the fight and waited for the killing blow. The assassins caught up with him on a road between Naples and Rome.

He was beheaded, his head, hands, and tongue soon impaled on display at the Forum and Mark Antony’s house.

“Cicero is dead.”

That’s how Shakespeare rendered the sudden fall of this great man. It was abrupt, violent, and final.

One of Caesar’s soldiers, Gaius Asinius Pollio, would write one of the most insightful epitaphs for Cicero:

Would that he had been able to endure prosperity with more self-control, and adversity with more fortitude. … He invited enmity with greater spirit than he fought it.

Indeed.

* Just as Zeno’s incident with the lentils is loaded with class implications, so too is Cicero’s association with the “lowly” chickpea.

Every few generations—or perhaps, every few centuries—a man is born with an iron constitution that consists of harder stuff than even his hardiest peers. These are the figures who come to us as myths and legends.

My God, we think, how did they do it? Where did that strength come from? Will we ever see a person like that again?

Marcus Porcius Cato was one of these men. Even in his own time it was a common expression: “We can’t all be Catos.”

This superiority was almost in his blood. He was born in 95 BC to a family that, despite its early plebeian origins, was, by his birth, firmly entrenched in Rome’s aristocracy. His great-grandfather, Cato the Elder, began his career as a military tribune and rose through the ranks as quaestor, aedile, praetor, all the way to consul in 195 BC, all the while earning a fortune in agriculture and making his name fighting for the ancestral customs (mos maiorum) against the modernizing influences of an ascendant empire. Ironically, the one influence most important to Cato that his great-grandfather fought most stridently against with his conservative zeal was philosophy. It was he, after all, who had wanted to throw the Athenian philosophers from Diogenes’s diplomatic mission out of Rome in 155 BC.

How perfect it was that his great-grandson, known as Cato the Younger, would become a famous philosopher, though we should note that Cato the Younger was no Carneades or Chrysippus. There would be no clever dialectics for him. He was cut from a different cloth than even a genius like Posidonius. Nearly every Stoic before and after was in part famous for what they said and wrote. Alone among them, Cato would achieve towering fame not for his words, but for what he did and for who he was. It was only on the pages of his life that he laid down his beliefs as a monument for all time, earning fame greater than any of his ancestors or his philosophical influences.

Not that you would have expected it at first.

As with Cleanthes before him and Winston Churchill nearly two thousand years after him, Cato’s early school days were underwhelming. His tutor, Sarpedon, found him obedient and diligent, but thought he “was sluggish of comprehension and slow.” There were flashes of brilliance—what Cato did understand stuck in his mind like it had been carved into stone. He was disruptive—not behaviorally (one struggles to imagine this disciplined boy ever acting out), but with his imperious and intense demeanor. He demanded an explanation for every task that was assigned to him, and luckily, his tutor chose to encourage this commitment to logic rather than beat it out of his young charge.

Physical force would have never worked on Cato anyway. There is a story about a powerful soldier visiting Cato’s home to argue over some citizenship issue during his childhood. When the determined soldier asked Cato to take up his cause with his uncle, who was serving as his guardian as well as tribune of the plebs, Cato ignored him. The soldier, disliking Cato’s lack of deference, attempted to frighten him. Cato, only four years old, stared back, unmoved. Next thing he knew, the soldier was holding him by the feet over a balcony. Cato remained not only unafraid, but wordless and unblinking, and the soldier, realizing he had been beaten, set the boy down, saying that if Rome were filled with such men he’d never convince anyone. It was the first of a lifetime of battles of political will for Cato, and also a preview of the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 18.9.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Beruf / Finanzen / Recht / Wirtschaft |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-105779-0 / 0001057790 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-105779-1 / 9780001057791 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 13,3 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich