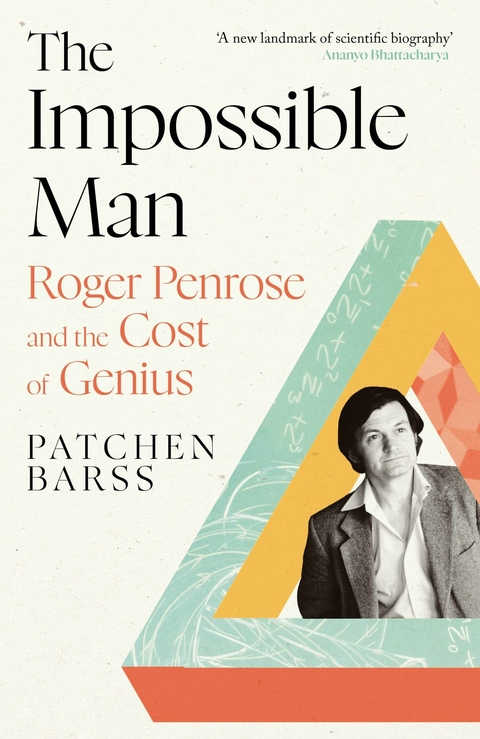

Impossible Man (eBook)

352 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-933-3 (ISBN)

Patchen Barss is a Toronto-based science journalist who has contributed to the BBC, Nautilus Magazine, Scientific American, and the Discovery Channel (Canada), as well as to many science and natural history museums. His previous books include The Erotic Engine: How Pornography has Powered Mass Communication, from Gutenberg to Google, and Flow Spin Grow: Looking for Patterns in Nature.

A Guardian Best Science Book of the YearThe first biography - 'a stunning achievement' (Kai Bird, American Prometheus) - of the dazzling and painful life of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Roger PenroseWhen he was six years old, Roger Penrose discovered a sundial in a clearing near his house. Through that machine made of light, shadow, and time, Roger glimpsed a "e;world behind the world"e; of transcendently beautiful geometry. It spurred him on a journey to become one of the world's most influential mathematicians, philosophers, and physicists. Penrose would prove the limitations of general relativity, set a new agenda for theoretical physics, and astound colleagues and admirers with the elegance and beauty of his discoveries. However, as Patchen Barss documents in The Impossible Man, success came at a price: He was attuned to the secrets of the universe, but struggled to connect with loved ones, especially the women who care for or worked with him. Both erudite and poetic, The Impossible Man draws on years of research and interviews, as well as previously unopened archives to present a moving portrait of Penrose the Nobel Prize-winning scientist and Roger the human being. It reveals not just the extraordinary life of Roger Penrose, but asks who gets to be a genius, and who makes the sacrifices that allow one man to be one.

Patchen Barss is a Toronto-based science journalist who has contributed to the BBC, Nautilus Magazine, Scientific American, and the Discovery Channel (Canada), as well as to many science and natural history museums. His previous books include The Erotic Engine: How Pornography has Powered Mass Communication, from Gutenberg to Google, and Flow Spin Grow: Looking for Patterns in Nature.

PROLOGUE

Courtesy of Owen Egan.

On Tuesday, December 8, 2020, Roger Penrose awoke alone in his Oxford flat. He walked barefoot and silent to the kitchen and pulled a pot of coffee from the refrigerator. He brewed coffee every Friday, stored it cold, and microwaved it cup by cup throughout the week.

As he splashed milk in his mug, he idly considered the death of the universe. The cold globules of lactose, protein, and fat spread through the hotter liquid, creating graceful clouds and tendrils. One stir of the spoon, and the shapes disappeared, leaving a mugful of monochromatic, pattern-less brown liquid.

This was the fundamental path of all things—islands of hot and cold flowing into one another, mixing and churning to create beautiful, ephemeral patterns before disappearing into a shapeless, uniform distribution of matter and energy. As time grinds up the future to make the past, the universe moves relentlessly toward greater entropy. It will one day reach a “heat death,” a state of inert equilibrium, with temperature and density the same and unchanging in every direction at every scale.

Roger had recently separated from Vanessa Thomas, his wife of more than thirty years. In his late eighties, living on his own for the first time in decades, he kept life as efficient and simple as possible. He ate plain meals of fish and vegetables or bread and cheese, with J. S. Bach or BBC Radio for company.

In the months since the United Kingdom went into pandemic lockdown, Vanessa had been delivering groceries, medication, and other necessities. She texted when she’d left bags outside his door, and he pulled them in.

Every two weeks, he chopped and mixed walnuts, almonds, crystallized ginger, and shredded wheat into a large batch of muesli. He used one of his flat’s two bathtubs for banana storage. He submerged them in a plastic container in the tub, keeping them underwater using a heavy orange-and-blue glass plaque he had received in 2013 from the University of Texas, San Antonio—a thank you for delivering a talk titled “Seeing Signals from Before the Big Bang” for the school’s Distinguished Visiting Lecture Series.

Roger had devoted his life to understanding the past, present, and future of the universe. He was acutely aware of how every cup of coffee will eventually cool to room temperature, every chunk of stone and ice flying through space will erode into its constituent parts, every star will eventually sputter out of existence, every galaxy will collapse, and even the last surviving black holes will ultimately boil away into an oblivion of scattered radiation.

Roger didn’t accept this depressing fate. The way he told the story, the universe had been around much longer than most people thought, and its distant future portended renewal and rebirth rather than a slow, gradual death. Few other physicists shared his view: Roger’s theories of cyclical cosmology had left him as isolated in the world of physics as he was in his own flat.

He checked the clock on his phone. Time was progressing at its usual steady rate of sixty minutes per hour, twenty-four hours per day. Roger, though, also knew the passage of time wasn’t the brutal, indifferent entropy factory it seemed. In fact, when he found doing so useful, he questioned whether time passed at all.

People typically perceive the flow of time like the stream of words in a book—a sequential, page-by-page journey from the beginning of the story to the end. But from another perspective, all those pages exist simultaneously: readers can hold the entire book in their hands at once, even if they can only experience one word at a time. Relativity—Albert Einstein’s astoundingly powerful theory that formed the basis for much of Roger’s life work—treats the universe as a static object in which the past, present, and future are like the pages of a cosmic book. Time seems to flow from one event to the next, but viewed in four dimensions rather than three, established history and the seemingly unwritten future coexist with equal reality.

Roger found this idea of a block universe fascinating and convenient. He could hold all of space-time in his mind at once: the distant past and future; the inaccessible regions beyond the visible universe; the interiors of black holes and the auras of distant dying galaxies. In a block universe, the passage of time was an illusion. Aging, death, and loss shed their significance. In a block universe, Roger could pretend that his own time and energy had no limit.

He resisted any thought of slowing down—he still published and lectured like a new scholar out to prove himself. He shrugged away his fame, his best-selling books, his long, distinguished academic career. His work remained unsettlingly unfinished.

He wilfully ignored medical issues—high blood pressure, macular degeneration, mobility problems, subtle but perceptible cognitive decline—that created challenges for his work and personal life.

He could concentrate when uninterrupted, but small disruptions could throw him off for hours as he struggled to recover his train of thought. He had increasing difficulty recalling names and words and often grew frustrated with his inconsistent memory.

He had become clumsy at hunting and pecking on his laptop, which made writing painstakingly slow. He kept a piece of card jammed under the caps lock key to stop himself from accidentally depressing it and wasting hours writing paragraphs in useless all caps. Editors willingly moved deadlines for him, but no amount of time ever seemed sufficient.

His eyes had also betrayed him, blurring shapes and obscuring words on the page. He’d had a customized magnifier embedded in the right lens of his thick glasses, and by closing one eye and holding a book or paper up to his nose, he could still read. For email and digital publications, he bought the largest computer screen he could find and blew the text up to marquee-sized letters. He rolled his office chair back from the display and held a monocular provided by the National Health Service up to his eye, swivelling back and forth to read each line.

Since he was fourteen, he had kept a journal in which he jotted down ideas and drawings. He had filled dozens of books over his lifetime and still kept one within arm’s reach as he researched. The once confident and graceful lines of his diagrams and sketches, though, had become shakier and less precise. His drawings looked more childlike now than they had when he was six years old.

When he lectured, he memorized the order of his slides, because he could not see them during the presentation. If a slide happened to be missing or upside down, he sometimes wouldn’t know until someone told him. He had unwillingly begun using PowerPoint for some talks but still preferred the hundreds of colourful, hand-drawn acetate transparencies he kept carefully ordered in shelved stacks in his home office.

Roger ignored time as much as he could, carrying on as though he were still the same productive, creative, and inspired mathematician he had been for more than sixty years.

On a typical day, he left his dirty dishes in the sink, turned off the radio, and settled into his office to read recent scientific papers and pore over maps of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation. He usually made just one outing a day: an hour-long walk along nearby canals or to the bakery in the city centre that made his favourite chocolate biscuits and multigrain bread. As a COVID-19 precaution, he held his breath each time he passed another human being.

This December day, though, was not typical. Instead of his usual rumpled shirt, oversized sweater, and well-worn, wide-wale corduroys, he chose a crisp shirt, tie, and fitted suit. He tamed his wispy grey hair and left his cosmology equations.

Dishes in sink, stick in hand, he descended two flights of stairs and exited to the drive where a car idled, waiting to take him into London. Reaching the Swedish ambassador’s residence took a little over an hour. There, in a sparse outdoor ceremony attended by Vanessa and their twenty-year-old son Max, he accepted the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Later that afternoon he returned home and put the Nobel medal away in the same cupboard where he kept his Order of Merit, his Eddington, Dirac, and Knight Bachelor medals, and several dozen other honorary degrees, plaques, certificates, and honours.

With that out of the way, he changed into comfortable clothes and went back to work.

He won the Nobel for a 1965 paper proving that large dying stars would inevitably collapse to a point of infinite density known as a singularity. His singularity theorem had disrupted the world of theoretical physics, demonstrating the incompleteness of Einstein’s relativity. The quest to discover new physics to describe what happens inside a black hole continues at elite research institutes around the world to this day.

Nearly fifty-six years passed between Roger’s publishing his singularity theorem and the day the Swedish ambassador presented him with a 175-gram disk of eighteen-carat gold bearing the embossed image of Alfred Nobel.

His journey to the most prestigious prize in physics, though, began even earlier.

Roughly 13.7 billion years before Roger won the Nobel Prize, a hot, dense universe wrenched into existence. The new universe was tiny: all of the reality we now know as the visible universe resided in a point possibly a billionth the size of a proton. This point contained the raw material that would become light and electricity, gravity and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | Integrated photos |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Physik / Astronomie ► Quantenphysik | |

| Schlagworte | Black Holes • Brian Cox • Cosmology • Infinite Monkey Cage • Maths • Nobel prize • oppenheimer • Quantum Physics • Science • science biography • science writing • Scientist • Stephen Hawking |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-933-5 / 1838959335 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-933-3 / 9781838959333 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich