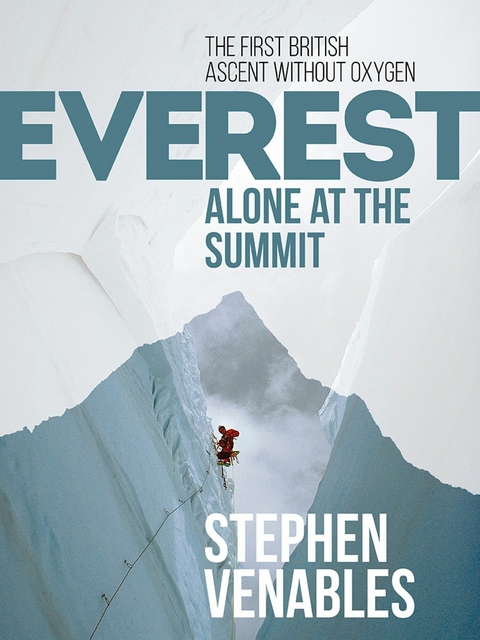

Everest: Alone at the Summit (eBook)

Vertebrate Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-912560-04-2 (ISBN)

Stephen Venables is a mountaineer, writer, broadcaster and public speaker, and was the first Briton to climb Everest without supplementary oxygen. Everest was a thrilling highlight in a career that has taken Stephen right through the Himalaya, from Afghanistan to Tibet, making first ascents of many previously unknown mountains. His adventures have also taken him to the Rockies, the Andes, the Antarctic island South Georgia, East Africa, South Africa and of course the European Alps, where he has climbed and skied for over forty years. The stories of these travels have enthralled Stephen's lecture audiences all over the world. He has appeared in television documentaries for the BBC, ITV and National Geographic, presented for Radio 4 and appeared in the IMAX movie Shackleton's Antarctic Adventure. Stephen has also authored several best-selling books on climbing in the high mountains.

In 1988, Stephen Venables became the first Briton to summit Everest without oxygen. Everest: Alone at the Summit is the story of his thrilling journey. Near-impossible challenges are conquered with determination and strength, and the experience of an expedition on the world's highest mountain is recounted in a refreshingly honest light. The Kangshung Face remains the least frequented of Everest's flanks due to its narrow gullies, hanging glaciers and steep rock buttresses. This, however, did not deter Venables and his team of three international climbers, Ed Webster, Robert Anderson and Paul Teare, who not only attempted this dangerous route, but did so without the use of supplementary oxygen testing boundaries, exploring the unknown and pushing the limits of human endurance. ' I forced my mind to concentrate on directing all energy to those two withered legs. The effort succeeded and I managed six faltering steps down the slope, sat back for a rest, then took six steps more, then again six steps. It was going to be a long tedious struggle, but I knew now that I was going to make it.'Venables' account of survival and success is fully immersive. He details the highs the unique bonds made on the mountain, the stunning scenery, and the triumph of reaching the summit as well as the lows: the threat of deadly high-altitude illness, turbulent weather and the exhaustion-induced hallucinations. Throughout it all, Venables' drive to keep going amidst hardship and his willingness to succeed is powerful readers will find themselves invested in this extraordinary narrative from the start. As Lord Hunt, the leader of Everest's 1953 expedition, observes in the foreword: 'People who, in this age of ease and plenty, pause to reflect upon the reason why some prefer to do things the hard way, could hardly do better than read this book.'

The expedition was over and we were on our way home, climbing up to the first of the high passes we had to cross on the long drive to Lhasa. Once again, the wheels spun, flinging mud up against the banks of the road. On each side the snow was piled up high, but from the raised seats of our Landcruiser we could look out over the white land. It was 4 November 1987. Two and a half weeks had now passed since Tibet had been swept by the worst storm in living memory, but the wide spaces of the plateau, normally brown and dry, still lay deep under snow.

At the top of the pass we waited for the other vehicle to catch up. Everyone got out to look back for the last time to Shisha Pangma, the mountain which had dominated our lives for the last two months.

There it all was: the great jumble of the icefall and, above it, the ramp, curving round to Camp 2 and the headwall, which we had laboured so hard to fix before the big storm swept through the length of the Greater Himalaya, reaching Tibet on 17 October. The devastation had been appalling, but afterwards we had just managed to salvage enough food and gear from the wrecked tents to make another attempt on the mountain, breaking trail through deep drifts and laboriously re-excavating the ropes up to Camp 2. From there, Luke Hughes and I had continued for another two days up the long South Ridge. Now from a distance we could really gauge the true scale of that immense ridge, the great sweep up to the 7,486-metre summit of Pungpa Ri, the descent on the far side and then more ridge, rising in great steps to the 8,046-metre summit of Shisha Pangma itself. We could see the exact point where Luke and I had stopped to dig an emergency snow cave at 7,700 metres and huddle through the night, sheltering from the vicious jet-stream wind. The temperature had been -35°C and, with the wind unabated, in the morning we had been forced to turn back, less than 400 metres from the top.

Now winter had arrived, our time was up and we were leaving empty handed. The surly Chinese drivers told us to hurry up with our photographs and we left, driving away down the far side of the pass.

The end of an expedition is nearly always a time for ambivalent feelings. I was excited to be going home after four months in Asia, but also clinging nostalgically to many happy memories of those months. First there had been the long trek across the Karakoram in Pakistan – days spent with Duncan and Phil on Snow Lake, the wild descent down an unknown glacier to Shimshal, the journey up the Hispar with Razzetti, camping in flower-filled meadows, the return to Snow Lake and my solo first ascent of a beautiful granite tower. Then there had been the long journey south to Rawalpindi and on by train through the Punjab and the Sind desert, right down to Karachi where I joined the Shisha Pangma expedition transferring for the flight to Kathmandu. We had trekked through the monsoon-soaked forests of Nepal to Tibet. Then, under brilliant blue skies, we had worked at the new route on Shisha Pangma. It had been a huge expedition with too many people for my taste; but it had been fun, and even during the three days of the storm, digging constantly to save tents and lives from the crushing snowdrifts, the radio calls between camps had been alive with humour and friendship. There was now just this nagging regret about not reaching the summit. So many people had put so much effort into the long improbable route, and despite the storm we had come so close to success that I found it more difficult than usual to be philosophical about being forced to turn back so near the top.

Dusk was falling as we entered the wide valley of the Phung Chu. It was a magical evening with a full moon riding the darkening sky. Ruined towers and battlements, relics of Tibet’s destroyed past, were silhouetted against the luminous hills, with dark figures of Tibetan people, on foot and on horseback, making their way homeward across the plain. We rounded a corner of the low hills and suddenly we were heading back south towards the great Himalayan chain and there, unmistakable on the horizon, was Everest.

The driver insisted we drive on to the official photo spot before stopping and it was almost dark when we pulled up beside a frozen stream. We were just in time. For a few precious moments the swirling clouds were pink and orange, the green ice at our feet was suffused with warm pastel tints and in front of us the rocky pyramid of Everest glowed deep blood red. It was now several weeks since the day on Shisha Pangma when I had enjoyed the sudden thrill of recognition, seeing Everest for the very first time. For weeks it had dominated our view east from the high camps but now we were seeing it from much closer. Some of my Shisha Pangma companions would be returning in less than four months with the British Services Expedition to attempt this northern side of the mountain; and as I stared up at the North-East Ridge, the Great Couloir, Changtse, the Yellow Band, the West Ridge – all those features so redolent of mountaineering history and legend – I could not help feeling a twinge of envy.

The colour faded quickly and we drove on into the darkness. The only sound in our vehicle was the drone of the engine and everyone seemed lost in his own thoughts. The poignant magic of that beautiful evening, and now the silver moonlight on the hills, seemed to intensify my own bittersweet nostalgia. Unlike my friends who were to attempt Everest, I still had no definite plans for the following year; but the last four months in the Himalaya had brought such a wealth of experience and fulfilment, happiness and regrets, success and disappointment, new mountains, new friends and new possibilities, that I would have to return, as I had been returning for the last ten years.

A week later I was back in London. I still felt tired and wasted from our exertions on Shisha Pangma and the long days of travelling across Tibet and China. For the time being mountains could wait and any future expeditions were far from my mind that Thursday evening, when I phoned my parents. My mother knew that I needed cheering up after the disappointment on Shisha Pangma and was obviously very excited when she passed on the message to telephone someone called Anderson: ‘I should ring him soon. It’s an invitation – a very nice invitation.’

I knew immediately that it must be Everest.

My mother had few details. Robert Anderson was an American who apparently wanted me to join his Everest expedition the following year. He had not said how many people were going, what route they were trying or why he wanted me; but if I was interested I should telephone him in New Zealand. I failed to get through to him that weekend and my first Everest invitation was still a mystery the following Monday when I travelled up to Manchester for a meeting of the British Mountaineering Council international committee. Unlike some committees, this one has concrete business to do – the distribution of Sports Council grants to British expeditions. We had disposed of a few hundred pounds when the chairman asked: ‘What about this one – American-New Zealand Everest?’

‘No, we don’t give them anything,’ explained Andy, the secretary, ‘but they are eligible for an MEF grant.’

‘Oh, yes. A New Zealander …’

‘Yes, Peter Hillary’s on the list.’

I didn’t have a copy of the form and tried to conceal my excitement as I asked my neighbour to pass over his. The others had moved on to the next application as I examined the Everest details: Spring 1988. Leader’s name Robert Anderson, American, thirty, reached 28,200 feet on the West Ridge in 1985 … then five more names. I only recognised the American Ed Webster – recollections of fine photographs – and of course Peter Hillary, a well-known Himalayan climber, lumbered with the additional fame of being Sir Edmund’s son. Because he was a New Zealander he enabled the expedition to qualify for a grant, or at least official recognition, from the British Mount Everest Foundation. This Anderson, whoever he was, had only filled in the barest details, but under ‘objective’ he had put enough to give me a little stab of fear: ‘Everest, East Face.’

As the meeting progressed and we discussed the relative merits of Ecuadoran volcanoes, unknown lumps in Pakistan and famous 8,000-metre giants, I kept on glancing back surreptitiously at the Everest form. My name was not on the list, but this was clearly the expedition on which I was supposed to have been invited.

My mind was racing on the late train back to London and when I eventually got to bed at about 4 a.m. I could not sleep. Soon the dawn birds were starting their racket in the street outside as I turned restlessly in bed, frightened and excited about the great East Face – the Kangshung Face of Everest.

I soon gave up the idea of sleeping, had some breakfast and started the day’s work of wading through four months’ mail. That evening I finally got through to Robert Anderson. For some reason I expected the American 12,000 miles away to be all gushing, welcoming bonhomie, so I was a little put out by his cool response.

‘Well it’s not definite. I’m just asking around to see who’s interested.’

‘And you’re really trying the East Face?’

‘Yes, it’s the only side I could get a permit for this soon. I want to try a new route, or maybe a lightweight...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.12.2018 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | John Hunt |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Schlagworte | 8000 metres • Adventure • adventure biography • Adventure Story • alpine climbing • Chris Bonington • Climbing • climbing without oxygen • Ed Webster • Everest • Everest 88 • Expedition • explorers • famous climbers • first ascents • free solo • high-altitude climbs • ice climbing • John Hunt • Kangshung Face • Kathmandu • Mountaineering • mountaineering book • Mountains • Mount Everest • mount everest books • Nepal travel • Paul Teare • Robert Anderson • rock climbing • sherpa story • sports biography • Stephen Venables • summit • Survival Story • The Himalayas • Tibet travel • travel in asia • trekking books |

| ISBN-10 | 1-912560-04-6 / 1912560046 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-912560-04-2 / 9781912560042 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich