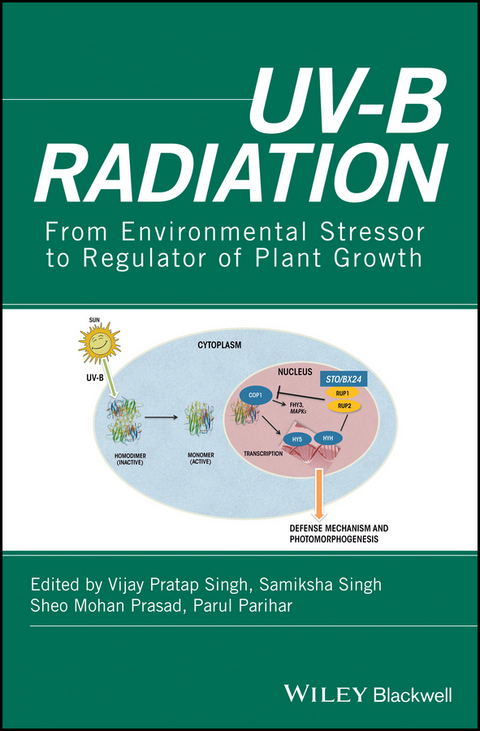

UV-B Radiation (eBook)

Ultraviolet B (UV-B) is electromagnetic radiation coming from the sun, with a medium wave which is mostly absorbed by the ozone layer. The biological effects of UV-B are greater than simple heating effects, and many practical applications of UV-B radiation derive from its interactions with organic molecules.Considered particularly harmful to the environment and living things, what have scientific studies actually shown?

UV-B Radiation: From Environmental Stressor to Regulator of Plant Growth presents a comprehensive overview of the origins, current state, and future horizons of scientific research on Ultraviolet B radiation and its perception in plants. Chapters explore all facets of UV-B research, including the basics of how UV-B's shorter wavelength radiation from the sun reaches the Earth's surface, along with its impact on the environment's biotic components and on human biological systems. Chapters also address the dramatic shift in UV-B research in recent years reflecting emerging technologies; showing how historic research which focused exclusively on the harmful environmental effects of UV-B radiation has now given way to studies on potential benefits to humans. Topics include:

• UV-B and its climatology

• UV-B and terrestrial ecosystems

• Plant responses to UV-B stress

• UB- B avoidance mechanisms

• UV-B and production of secondary metabolites

• Discovery of UVR8

Timely and important, UV-B Radiation: From Environmental Stressor to Regulator of Plant Growth is an invaluable resource for environmentalists, researchers and students, into the state-of-the-art research being done on exposure to UV-B radiation.

About the Editors

Vijay Pratap Singh is Assistant Professor, Govt. Ramanuj Pratap Singhdev Post Graduate College, Chhattisgarh, India.

Samiksha Singh is Research Scholar, Ranjan Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Laboratory, Department of Botany, University of Allahabad, India.

Sheo Mohan Prasad is Professor, Ranjan Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Laboratory, Department of Botany, University of Allahabad, India.

Parul Parihar is Research Scholar, Ranjan Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Laboratory, Department of Botany, University of Allahabad, India.

Ultraviolet-B (UV-B) is electromagnetic radiation coming from the sun, with a medium wavelength which is mostly absorbed by the ozone layer. The biological effects of UV-B are greater than simple heating effects, and many practical applications of UV-B radiation derive from its interactions with organic molecules. It is considered particularly harmful to the environment and living things, but what have scientific studies actually shown? UV-B Radiation: From Environmental Stressor to Regulator of Plant Growth presents a comprehensive overview of the origins, current state, and future horizons of scientific research on ultraviolet-B radiation and its perception in plants. Chapters explore all facets of UV-B research, including the basics of how UV-B's shorter wavelength radiation from the sun reaches the Earth's surface, along with its impact on the environment's biotic components and on human biological systems. Chapters also address the dramatic shift in UV-B research in recent years, reflecting emerging technologies, showing how historic research which focused exclusively on the harmful environmental effects of UV-B radiation has now given way to studies on potential benefits to humans. Topics include: UV-B and its climatology UV-B and terrestrial ecosystems Plant responses to UV-B stress UB- B avoidance mechanisms UV-B and production of secondary metabolites Discovery of UVR8 Timely and important, UV-B Radiation: From Environmental Stressor to Regulator of Plant Growth is an invaluable resource for environmentalists, researchers and students who are into the state-of-the-art research being done on exposure to UV-B radiation.

ABOUT THE EDITORS VIJAY PRATAP SINGH is Assistant Professor, Govt. Ramanuj Pratap Singhdev Post Graduate College, Chhattisgarh, India. SAMIKSHA SINGH is Research Scholar, Ranjan Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Laboratory, Department of Botany, University of Allahabad, India. SHEO MOHAN PRASAD is Professor, Ranjan Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Laboratory, Department of Botany, University of Allahabad, India. PARUL PARIHAR is Research Scholar, Ranjan Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Laboratory, Department of Botany, University of Allahabad, India.

1

An Introduction to UV‐B Research in Plant Science

Rachana Singh1, Parul Parihar1, Samiksha Singh1, MPVVB Singh1, Vijay Pratap Singh2 and Sheo Mohan Prasad1

1 Ranjan Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Laboratory, Department of Botany, University of Allahabad, Allahabad, India

2 Government Ramanuj Pratap Singhdev Post Graduate College, Baikunthpur, Koriya, Chhattisgarh, India

1.1 The Historical Background

About 3.8 × 109 years ago, during the early evolutionary phase, the young earth was receiving a very high amount of UV radiation and it is estimated that, at that time, the sun was behaving like young T‐Tauristars and was emitting 10,000 times greater UV than today (Canuto et al., 1982). Then, the radiance of the sun became lower than it is in the present day, thereby resulting in temperatures below freezing. On the other hand, due to high atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) level, which was 100–1000 times greater than that of present values, liquid water did occur and absorbed infrared (IR) radiation, and this shaped an obvious greenhouse effect (Canuto et al., 1982). Due to the photosynthesis of photosynthetic bacteria, cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae, oxygen (O2) was released for the first time into the environment, which led to an increase of atmospheric O2 and a simultaneous decrease of atmospheric CO2.

About 2.7 × 109 years ago, due to the absence of oxygenic photosynthesis, oxygen was absent from the atmosphere. About 2.7 × 109 years ago, with the deposition of iron oxide (Fe2O3) in Red Beds, aerobic terrestrial weathering occurred and, at that time, O2 was approximately about 0.001% of the present level (Rozema et al., 1997). In proportion with gradual atmospheric O2 increase, the accumulation of stratospheric ozone might have been slow. Alternatively, about 3.5 × 108 years ago, due to a sheer rise in atmospheric oxygen, it might have reached close to the present levels of 21% (Kubitzki, 1987; Stafford, 1991). Nevertheless, terrestrial plant life was made possible by the development of the stratospheric ozone (O3) layer, which absorbs solar UV‐C completely and a part of UV‐B radiation, thereby reducing the damaging solar UV flux on the earth’s surface (Caldwell, 1997).

Before focusing on the various aspects of UV‐B radiation, we should firstly understand the electromagnetic spectrum. The electromagnetic spectrum consists of ultraviolet (UV) and visible (VIS) radiations (i.e. also PAR). The wavelength ranges of UV and visible radiation are listed in Table 1.1. Solar radiations, with a longer wavelength, are called infrared (IR) radiations. The spectral range between 200 and 400 nm, which borders on the visible range, is called UV radiation, and is divided into three categories: UV‐C (100–280 nm), UV‐B (280–315 nm) and UV‐A (315–400 nm). The shorter wavelengths of UV get filtered out by stratospheric O3, and less than 7% of the sun’s radiation range between 280 and 400 nm (UV‐A and UV‐B) reaches the Earth’s surface.

Table 1.1 Regions of the electromagnetic spectrum together with colours, modified from Iqbal (1983) and Eichler et al. (1993).

| Wavelength (nm) | Frequency (THz) | Colour |

| 50 000–106 | 6–0.3 | far IR |

| 3000–50 000 | 100–6 | mid IR |

| 770–3000 | 390–100 | near IR |

| 622–770 | 482–390 | red |

| 597–622 | 502–482 | Orange |

| 577–597 | 520–502 | yellow |

| 492–577 | 610–520 | Green |

| 455–492 | 660–610 | blue |

| 390–455 | 770–660 | violet |

| 315–400 | 950–750 | UV‐A |

| 280–315 | 1070–950 | UV‐B |

| 100–280 | 3000–1070 | UV‐C |

The level of UV‐B radiation over temperate regions is lower than it is in tropical latitudes, due to higher atmospheric UV‐B absorption, primarily caused by changes in solar angle and the thickness of the ozone layer. Therefore, the intensity of UV‐B radiation is relatively low in the polar regions and high in the tropical areas. Over 35 years ago, it was warned that man‐made compounds (e.g. CFCs, HCFCs, halons, carbon tetrachloride, etc.) cause the breakdown of large amounts of O3 in the stratosphere (Velders et al., 2007) thereby increasing the level of UV‐B reaching the Earth’s surface. Increase in the UV‐B radiation has been estimated since the 1980s (UNEP, 2002), and projections like the Kyoto protocol estimate that, even after the implementation of these protocols, returning to pre‐1980 levels will be possible by 2050–2075 (UNEP, 2002).

1.2 Biologically Effective Irradiance

The term ‘biologically effective irradiance’ means the effectiveness of different wavelengths in obtaining a number of photobiological outcomes when biological species are irradiated with ultraviolet radiations (UVR). The UV‐B, UV‐A and photosynthetically active radiations (PAR; 400–700 nm) have a significant biological impact on organisms (Vincent and Roy, 1993; Ivanov et al., 2000). Ultraviolet irradiation results into a number of biological effects that are initiated by photochemical absorption by biologically significant molecules. Among these molecules, the most important are nucleic acids, which absorb the majority of ultraviolet photons, and also proteins, which do so to a much lesser extent (Harm, 1980).

Nucleic acids (a necessary part of DNA) are nucleotide bases that have absorbing centres (i.e. chromophores). In DNA, the absorption spectra of purine (adenine and guanine) and pyrimidine derivatives (thymine and cytosine), are slightly different, but an absorption maximum between 260–265 nm, with a fast reduction in the absorption at longer wavelengths, is common (Figure 1.1). In contrast with nucleic acids solutions of equal concentration, the absorbance of proteins is lower. Proteins with absorption maxima of about 280 nm most strongly absorb in the UV‐B and UV‐C regions (Figure 1.1). The other biologically significant molecules that absorb UVR are caratenoids, porphyrins, quinones and steroids.

Figure 1.1 Absorption spectra of protein and DNA at equal concentrations

(adapted from Harm, 1980).

1.3 UV‐B‐induced Effects in Plants

In the past few decades, a lot of studies have been made on the role of UV‐B radiation. Due to the fact that sunlight necessity for their survival, plants are inevitably exposed to solar UV‐B radiation reaching the earth’s surface. From the point of view of ozone depletion, this UV‐B radiation should be considered as an environmental stressor for photosynthetic organisms (Caldwell et al., 2007). However, according to the evolutionary point of view, this assumption is questionable.

Although UV‐B radiation comprises only a small part of the electromagnetic spectrum, the UV‐B reaching on earth’s surface is capable of producing several responses at molecular, cellular and whole‐organism level in plants (Jenkins, 2009). UV‐B radiation is readily absorbed by nucleic acids, lipids and proteins, thereby leading to their photo‐oxidation and resulting in promotional changes on multiple biological processes, either by regulating or damaging (Tian and Yu, 2009). In spite of the multiplicity of UV‐B targets in plants, it appears that the main action target of UV‐B is photosynthetic apparatus, leading to the impairment of the photosynthetic function (Lidon et al., 2012). If we talk about the negative impact of UV‐B, it inhibits chlorophyll biosynthesis, inactivates light harvesting complex II (LHCII), photosystem II (PSII) reaction centres functioning, as well as electron flux (Lidon et al., 2012).

The photosynthetic pathway responding to UV‐B may depend on various factors, including UV‐B dosage, growth stage and conditions, and flow rate, and also the interaction with other environmental stresses (e.g., cold, high light, drought, temperature, heavy metals, etc.) (Jenkins, 2009). The thylakoid membrane and oxygen evolving complex (OEC) are highly sensitive to UV‐B (Lidon et al., 2012). Since the Mn cluster of OEC is the most labile element of the electron transport chain, UV‐B absorption by the redox components or protein matrix may lead to conformational changes, as well as inactivation of the Mn cluster. The D1 and D2 are the main proteins of PSII reaction centres and the degradation and synthesis of D1 protein is in equilibrium under normal condition in light, however, its degradation rate becomes faster under UV‐B exposure thereby, equilibrium...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.2.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Botanik |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Ökologie / Naturschutz | |

| Technik ► Umwelttechnik / Biotechnologie | |

| Schlagworte | Applications • Biochemie • biochemistry • Biological effects • Biowissenschaften • Botanik • considered • Electromagnetic • Environment • Environmental Science • Environmental Studies • greater • Interactions • Layer • Life Sciences • many • medium wavelength • Molecules • Mostly • organic • Ozone • plant science • Practical • Radiation • radiation derive • Simple • Sun • ultravioletb • Umweltforschung • Umweltwissenschaften • UVB |

| ISBN-13 | 9781119143628 / 9781119143628 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich