Diagnosing Dental and Orofacial Pain (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-92498-3 (ISBN)

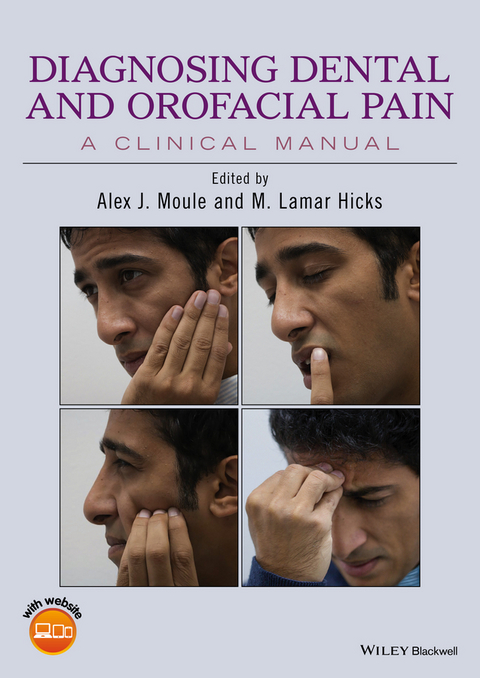

Diagnosing Dental and Orofacial Pain: A Clinical Manual approaches a complex topic in a uniquely practical way. This text offers valuable advice on ways to observe and communicate effectively with patients in pain, how to analyze a patients' pain descriptions, and how to provide a proper diagnosis of orofacial pain problems that can arise from a myriad of sources-anywhere from teeth, joint and muscle pain, and paranasal sinuses to cluster headaches, neuralgias, neuropathic pain and viral infections.

- Helps the student and practitioner understand the diagnostic process by addressing the exact questions that need to be asked and then analyzing verbal and non-verbal responses to these

- Edited by experts with decades of clinical and teaching experience, and with contributions from international specialists

- Companion website provides additional learning materials including videos, case studies and further practical tips for examination and diagnosis

- Includes numerous color photographs and illustrations throughout to enhance text clarity

Diagnosing Dental and Orofacial Pain: A Clinical Manual approaches a complex topic in a uniquely practical way. This text offers valuable advice on ways to observe and communicate effectively with patients in pain, how to analyze a patients pain descriptions, and how to provide a proper diagnosis of orofacial pain problems that can arise from a myriad of sources anywhere from teeth, joint and muscle pain, and paranasal sinuses to cluster headaches, neuralgias, neuropathic pain and viral infections. Helps the student and practitioner understand the diagnostic process by addressing the exact questions that need to be asked and then analyzing verbal and non-verbal responses to these Edited by experts with decades of clinical and teaching experience, and with contributions from international specialists Companion website provides additional learning materials including videos, case studies and further practical tips for examination and diagnosis Includes numerous color photographs and illustrations throughout to enhance text clarity

Alex J. Moule is an Associate Professor and Discipline Lead in Endodontics at the School of Dentistry, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. M. Lamar Hicks is Clinical Professor, Deans Faculty, Endodontics Division at the University of Maryland Dental School Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Contributors vi

Acknowledgments vii

About the Companion Website viii

1 Introduction 1

Alex J. Moule and M. Lamar Hicks

2 The Art of Listening - Communicating Effectively with a Patient in Pain 3

Andrew D. Wolvin

3 Causes of Pain in the Orofacial Region 6

Vishal R. Aggarwal, Alex J. Moule and M. Lamar Hicks

4 Gathering Information for an Accurate Pain Diagnosis 16

Alex J. Moule and M. Lamar Hicks

5 Analyzing Patients in Pain - Describing Pain and the Importance of Descriptors 19

Alex J. Moule and M. Lamar Hicks

6 Analyzing Patients in Pain - Observing Patients in Pain 23

Alex J. Moule and Tareq Al Ali

7 Analyzing Patients in Pain - Associations with Cold and Heat 36

Alex J. Moule and M. Lamar Hicks

8 Analyzing Pain Descriptions - Pain on Biting or Eating and Other Considerations 41

Alex J. Moule and M. Lamar Hicks

9 Analyzing Pain Descriptions - Time Analysis and the Diagnosis of Orofacial Pain 46

Alex J. Moule and M. Lamar Hicks

10 Analyzing Pain Descriptions - Factors Influencing the Pain 50

Alex J. Moule and M. Lamar Hicks

11 Tests and Testing 53

Alex J. Moule and Unni Krishnan

12 Diagnosing Dental Pain 61

Alex J. Moule and Unni Krishnan

13 Diagnosing Cracked (Crown Fractured) Teeth 68

Alex J. Moule

14 Diagnosing Joint and Muscle Pains 79

Chris Moule and Iven Klineberg

15 Diagnosing Pain Referral from Neck and Shoulders 89

Scott Cook and Alex J. Moule

16 Diagnosing Pain from the Sinuses 96

Unni Krishnan and Alex J. Moule

17 Diagnosing Tension Headaches and Migraine 103

David Mock

18 Diagnosing Cluster Headaches 106

Kerryn Green

19 Diagnosing Trigeminal Neuralgia 109

Kerryn Green

20 Viruses as a Cause of Orofacial Pain 113

Michael Apicella

21 Vascular Causes of Headaches 117

Mark Paine

22 Diagnosing Neuropathic Orofacial Pain 123

E. Russell Vickers and Alex J. Moule

23 Referral Strategies for Orofacial Pain Cases 130

F. Russell Vickers and Alex J. Moule

References 133

Index 140

Chapter 2

The Art of Listening – Communicating Effectively with a Patient in Pain

Andrew D. Wolvin

Introduction

Good health care is a partnership between the patient and the clinician – and with the rest of a clinical team. The center of this partnership is effective communication. Research reinforces that “communication between clinicians and patients has been recognized as an integral part of providing optimum patient care.”1 This clinician–patient partnership should be built on a relationship of trust. It requires that the clinician be comforting, caring and encouraging, asking and answering questions, offering clear explanations, and listening and checking understanding.2 Most patients who have orofacial pain seek advice first from a dentist. It is especially important with these patients to establish trust and develop good dentist–patient communication, which has been described as one that is purposeful: creating a good interpersonal relationship, exchanging information and deciding on the best course of treatment.3 Not surprisingly, most of the focus in studies of dentist–patient communication has centered on dentists, with little attention to the communication needs of patients themselves. A national survey, for example, which asked dentists about their communication strategies4 determined that good strategies that can be used include interpersonal communication, the teach-back method, patient-friendly materials and aids, the offering of assistance, and a patient-friendly practice. These communication techniques are what the dentist should say and/or do in interactions with patients.

However, since communication is a keystone of good patient care, it can be helpful to look more broadly at dentist–patient communication, not as dentist-centered, but as listening-centered. As the research stresses, communicating clinicians not only should utilize effective speaking skills, but also must engage in careful listening. Good clinical practice requires that you listen with your ears and your eyes to assess what you and the patient need to know, and what the patient already knows and wants to know.5 It is important to start any interaction with good listening.6 It is important to your diagnosis to know what the patient is experiencing and, to explore this, consider beginning your interaction with small talk that can help to establish a basic level of communication comfort. This often overlooked step is important for your patient to feel as much at ease as is possible in their interaction with you. This is challenging, of course, because if the patient has a significant orofacial pain problem, they will undoubtedly be apprehensive about what is wrong and what you will need to do to resolve the problem.

Beginning your interaction with small talk is time well spent, however, because you can learn a great deal about a patient’s issue by listening perceptively to them in the beginning. Consider not starting out with the traditional “How are you?” greeting as a patient, understandably, cannot return the standard “Fine, thanks” response – thinking rather, “I’m here for you to determine how I am!” Instead, starting out with answerable questions such as: “What is the temperature outside today?” or “How is the traffic out there?” or “You must be a Nationals fan?” can help you establish rapport and in the process reduce your patient’s anxiety.

Once you have provided a comforting opener, a question such as: “What can I do for you today?” establishes a good foundation to start your diagnosis. Listen closely then to what your patient tells you about his/her issue. Ask the necessary follow-up questions to get the details you need. Most of your patients are not schooled in dental health, so you will need to probe further as to what is the problem. To effectively listen to your patients, you have to ask all the relevant questions to prompt the details you require to make an accurate diagnosis. These prompts are important. You do not want to run the risk of the doorknob syndrome where the patient remembers to tell the health care provider the real issue only as the consultation is coming to an end. Furthermore, you will want to check your understanding to be sure that what you heard is what the patient intended to communicate, echoing the patient’s concerns by asking questions such as:

As I understand it, you’ve had this pain in the upper right side of your face for three days and it’s getting worse…

When considering questioning, it may be helpful to remember the journalist’s agenda: what, when, where, why and how, or more classically in pain diagnosis, the onset, duration, frequency, location, character, radiation, severity, the precipitating factors and the relieving factors all need to be addressed. How to phrase these questions and the relevance of the answers are the subjects of this manual.

At the same time, do not ignore the visual channel. Often, you can get a sense of a patient’s level of pain from their nonverbal demeanor – facial grimaces, rigid posture, clutching the chair. Also note whether the nonverbal reaction is or is not consistent with the verbal responses you are hearing. A patient might tell you that their pain level is a 2 on a 10-point linear analogue scale, but their facial tension might well register an 8, or vice versa. Also, research on nonverbal communication suggests that as much as 55% of the emotional component of a message is communicated through the face alone, because individuals are not skilled at controlling their facial expression (and eye behavior), especially when in pain.7 Additionally, pay particular attention to the manner in which a patient describes the location of their pain, as gestures and facial expression are often diagnostic for a given pain cause.

As your patient tells you about their orofacial pain problem, it is important to be there as a listener. You will want to attend to their narrative and to concentrate fully on what they have to say. In addition to your clinical observation procedures, do not be afraid to be emotionally empathetic and understanding to your patient as well. It is, of course, tempting in many situations to go straight to a diagnosis just as a patient launches into a description of an issue (after all, you will have heard this hundreds of times before). One study revealed that medical professionals tend to start directing the diagnostic discussion as early as 23 seconds into the intake interview,8 before a patient has had time to explain their problem. Such premature diagnosis can lead you astray. You want to be sure you have heard the full story from your patient’s perspective before coming to a conclusion, and to be aware that a diagnosis must fit the facts. It is risky to try to make the facts fit a diagnosis.

Listening to your patient’s perspective is the key to being a responsive communicator. Once you have obtained all the details you need, your communication goal is then to explain fully what their problem is, and what course of treatment will resolve the problem. This can be a challenge, because most patients tend to be highly anxious, so they may not fully comprehend what you are recommending. Adding to the communication difficulty may be the level of dental literacy your patient has and that many patients often have turned to the Internet to pre-diagnose (often misdiagnose) their problems before even making an appointment.

Consequently, a clear, comprehensible explanation of what is the problem and what is the solution to the problem is crucial. If it is necessary to use technical terms, be sure to explain/define those terms for the patient. And provide visual aids to enhance and reinforce your explanation. The visual channel is central to the way we listen. Listening research suggests that we visualize as we listen, so a good communicator takes us there visually. The use of video images, for example, of the patient’s mouth or teeth can be compelling and comprehensible for your patient.

Your nonverbal (vocal and visual) message is just as important as what you say verbally. Some research even suggests that the nonverbal is more important; as much as 93% of the impact of a message on a listener may be communicated through the vocal and visual channels.9,10 So try to position yourself so you have eye contact with your patient as you conduct your consultation. This visual connection reassures your patient that you are a caring clinician, and eye contact enables you to process how your patient is responding to your diagnosis. Likewise, be sensitive to your care-giving demeanor. Communicate in a warm, expressive vocal tone and with pleasant facial expression. It may seem self-evident to communicate that you care, yet be aware that it is tempting to look at the radiographs or at your computer screen while conducting this interview. I can think of some of my own health care providers who never look at me during a diagnosis, being focused on their computer, even to the point of having their back to me!

The clinician–patient interaction does not stop with the initial interview. The patient is often present for treatment purposes. It also is important to maintain a clear, compassionate communication approach throughout any treatment process. This can be difficult, of course, because you are concentrating on the technical...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.9.2016 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Medizin / Pharmazie ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete | |

| Studium ► 2. Studienabschnitt (Klinik) ► Anamnese / Körperliche Untersuchung | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Zahnmedizin | |

| Schlagworte | Dental Pain • dentistry • Dentistry Special Topics • Endodontics • Endodontie • Endodontik • jaw pain • joint pain • Medical Science • Medizin • Mundheilkunde • muscle pain • Non-Odontogenic Pain • odontogenic pain • Orofacial • Orofacial Pain • Orofaziale Schmerzen • Pain (including Headache) • Schmerzen, Kopfschmerzen • Spezialthemen Zahnmedizin • Tooth Fracture • tooth pain • Zahnmedizin • Zahnschmerz |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-92498-3 / 1118924983 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-92498-3 / 9781118924983 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich