Three More Archbishops of Milwaukee (eBook)

152 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-8244-2 (ISBN)

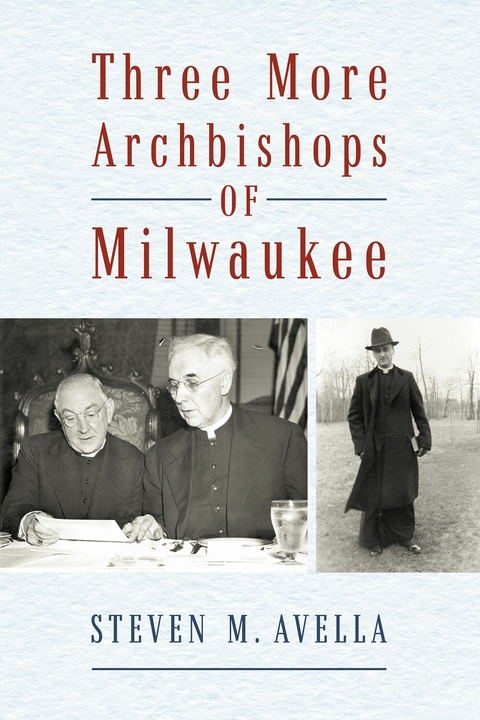

Steven M. Avella is a professor emeritus of Marquette University and priest of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee. He has authored several books on the history of Catholicism in Wisconsin, including In the Richness of the Earth: A History of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee 1843-1958, and Confidence and Crisis: A History of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, 1959-1977, and edited Milwaukee Catholicism: Essays on Church and Community (1991). He has also authored books on the history of Catholic life in Chicago, Sacramento, Reno, Colorado Springs, and Phoenix. Avella has conducted research in the Archives of the Archdioceses of Milwaukee and Chicago, and the Apostolic Vatican Archives. A graduate of the University of Notre Dame (Ph.D., 1985), he studied under the late Professor Philip Gleason. He served as President of the American Catholic Historical Association (2009-2010).

"e;Three More Archbishops of Milwaukee"e; offers an in-depth look at three Catholic archbishops who guided Milwaukee's archdiocese from 1930 to 1958: Samuel A. Stritch, Moses E. Kiley, and Albert G. Meyer. Although each archbishop brought a distinct temperament and leadership style to their role, they shared a foundational education from Roman seminaries, which played a crucial part in shaping their vision and governance. Samuel A. Stritch, the first U.S.-born archbishop of Milwaukee, arrived as the Great Depression gripped Wisconsin. His leadership focused on stabilizing faltering archdiocesan finances and energizing lay Catholic Action. Stritch's pastoral touch and accessibility endeared him to Milwaukeeans, and his eventual departure for Chicago was widely lamented. His successor, Moses E. Kiley, a native of Nova Scotia, was a stern and taciturn figure. He focused on planning and rebuilding as Milwaukee prospered after World War II. Kiley's strict rule, particularly with clergy, was accompanied by efforts to rebuild a cathedral and enhance archdiocesan institutions, including the seminary and orphanage. Albert G. Meyer, who followed Kiley, had extensive ties to Wisconsin, having served as rector of St. Francis Seminary and bishop of Superior. His tenure was marked by rapid expansion of parishes and schools, and he oversaw the largest period of growth in the archdiocese's history. Meyer also confronted challenges brought by the freeway system, suburbanization, and the shifting racial demographics in Milwaukee. Throughout their terms, all three archbishops brought a Roman-trained, uniform theological vision, providing a sense of continuity to Milwaukee Catholicism during a time of great transformation. Ethnic identities, though still important, began to fade in prominence as suburban life reshaped the community. Despite these shifts, the steady leadership of Stritch, Kiley, and Meyer offered stability and cohesion to Milwaukee Catholics in a period of immense social and institutional change.

Introduction

In 1955, Father Benjamin Blied, a professional historian and a former seminary teacher, self-published Three Archbishops of Milwaukee while he was the pastor of a rural parish in Johnsburg, Wisconsin. This and his other writings on Wisconsin Catholicism were an important contribution to local history.1 Written in Blied’s distinctive style, the book provided a lot of useful information about three relatively unknown prelates of Milwaukee: Michael Heiss (1881–1891), Frederick X. Katzer (1891–1903), and Sebastian Gebhard Messmer (1903–1930.) Blied was well qualified to write this work, as he had the ability to read German—the native language of these three bishops. In Three Archbishops, he combined what little documentary evidence then available with his own particular way of writing church history.2

Blied was sui generis.3 A native of Madison, he had a troubled childhood, but studied at Harvard University and the University of Wisconsin and earned his doctoral degree from Marquette University. Ordained to the priesthood in 1934, he spent a limited time in parishes until appointed to the faculty of Pio Nono College [high school] in St. Francis. According to his biography, he abandoned teaching history at Pio Nono in some dispute with fellow faculty members and resumed the life of a parish priest.4 He and the other legendary historian of the archdiocese, Monsignor Peter Leo Johnson (1888–1973) held each other in mutual contempt. The Roman-trained Johnson had, however, the favor of the archdiocese and a secure seat on the major seminary faculty. He not only had access to many historical records but also scores of students who could translate German texts for him.5 In 1960, Blied accepted a post on the faculty of Marian College in Fond du Lac. Here, too, he elicited a mixed reaction from the students and quarreled with the sisters over his living accommodations and their embrace of James Hanlon’s innovative ideas about self-actualization.6

His unique personality—especially his penchant for blunt talk—blended with his expertise in professional historical methodology. His distinct way of writing included definitive (and sometimes cryptic) statements, often without reference to his sources. The author met him and attempted to interview him about his work on Katzer, but Blied kept interrupting the taped interview by insisting at certain points that I turn off the recorder while he confided something utterly harmless.

He inherited a large sum of money from relatives and traveled extensively. In Fond du Lac, he bought his own home and made the city the object of his personal generosity. One of his charities included $145,000 for the beautification of the city’s Lakeside Park. He also contributed substantially ($10,000) to the building of a circular chapel on the campus of Marian College named for the biblical figure Dorcas. One of his last works were sketches of the archbishops of Milwaukee that were supposed to be included in a 1976 History of the Catholic Church in Wisconsin authored by Norbertine Father Leo Rummel. For whatever reasons they were excluded as “not being sufficiently respectful.”7 This text makes use of portions of that rejected manuscript as a tribute to Blied’s unique contributions to the history of the church in Wisconsin.

This book adds three more Milwaukee archbishops to the historical record: Samuel A. Stritch (1930–1940), Moses E. Kiley (1940–1953), and Albert G. Meyer (1953–1958). These three bishops were of different temperament and personality, but all had in common training in Rome during the early part of the twentieth century. This era was the high-water mark of what historians call a unitary Catholic culture brought about by four transformative experiences: the centralization of papal power, especially after the definition of papal infallibility at Vatican I (1871); the enthronement of Neo-Scholasticism as the official philosophy and theology of the church (1878); the papal condemnation of Modernism (1907); and the promulgation of the Code of Canon Law (1918). These developments effected a major change in world-wide Catholicism and had a profound impact on the development of the church in the United States.8 Historian Joseph M. White has noted that this was also a highly influential period for the formation of the clergy.9 Understanding this wider historical milieu is of supreme importance in contextualizing the tenures of these three very influential Milwaukee archbishops. They saw the church and the world through a common intellectual lens. Yet despite their common training, these were three unique men and the historical context for each of their administrations was quite different.

Samuel A. Stritch, the first U.S.-born archbishop of Milwaukee (and the first of Irish descent) was born in Nashville, Tennessee in August 1887 and studied in Rome from 1904 to 1911. He was a pastor and diocesan official in Nashville, and bishop of Toledo, Ohio. He arrived in Milwaukee just as the Great Depression was blanketing the state of Wisconsin. He spent considerable effort shoring up faltering archdiocesan finances and energizing lay Catholic Action. His departure for Chicago in 1940 was widely lamented by Milwaukeeans who remembered his kind ways and appreciated his willingness to move among them with ease. He lived the advice he gave one of his successors in Milwaukee: “Don’t run your diocese from behind a desk.”10

His successor, Moses Elias Kiley, was quite different from Stritch. Born in 1876, he was a native of Nova Scotia, and did not enter the seminary until his late twenties. He studied in Rome and was ordained for the Archdiocese of Chicago, where he worked in a parish and then in archdiocesan charities. After a time, he returned to Rome where he became the spiritual director of the North American College. He was appointed to the See of Trenton, New Jersey, in 1934 and six years later was transferred to Milwaukee. Kiley was taciturn and foreboding, but his thirteen years in Milwaukee were a period of relative prosperity, in equal parts due to his good planning and the revival of the local economy during and after World War II. Kiley ruled with an iron hand and was particularly hard on clergy. The last months of his life were spent in St. Mary’s Hospital in Milwaukee where he died on April 15, 1953.

His successor was the bishop of Superior, Wisconsin, and a former St. Francis Seminary rector, Albert G. Meyer. Meyer was the only native Milwaukeean to date to ever sit on the bishop’s throne in the cathedral of St. John the Evangelist. Born March 3, 1903, he was the son of a grocer who had a failing store on Warren Street on the near-east side of the city. He studied in Rome, was ordained in 1927, and remained in Rome until 1930 to finish a degree in sacred scripture. In 1931, he joined the faculty of St. Francis Seminary and in 1937 became the rector. In 1946, he was appointed the bishop of Superior, a diocese comprising the upper sixteen counties of Wisconsin. He remained there until September 1953 when he was selected to replace Kiley in Milwaukee. He spent five action-packed years in southeastern Wisconsin overseeing rapid parish growth, and the expansion of the school and seminary system. This was the greatest single epoch of expansion in archdiocesan history and required a pace that made him physically ill.

Each one of these men faced serious challenges presented by their times. Stritch had grave financial problems caused by the Great Depression. Kiley had to rebuild a burned-out cathedral, improve the growing archdiocesan seminary, and plan for a new orphanage. Meyer not only faced five years of rapid expansion but also the radical resculpting of the city of Milwaukee by the freeway system, the shift of the Catholic population to the suburbs, and the beginnings of rapid racial succession.

Their Roman training and uniform theological views provided a continuity to their era and a sense of stability to the experience of being Catholic. During their time of leadership, Milwaukee Catholicism was changing dramatically. Ethnic identity and its manifestations (churches, priests, etc.) did not disappear, but it waned as a defining feature of archdiocesan Catholic life. Replacing it was a cohesive Catholic culture that was underpinned by a fixed theological and ecclesiological vision.11 These three prelates did not suffer questions about their roles and authority as bishops. However, the way each one exercised the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 19.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-8244-2 / 9798350982442 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,7 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich