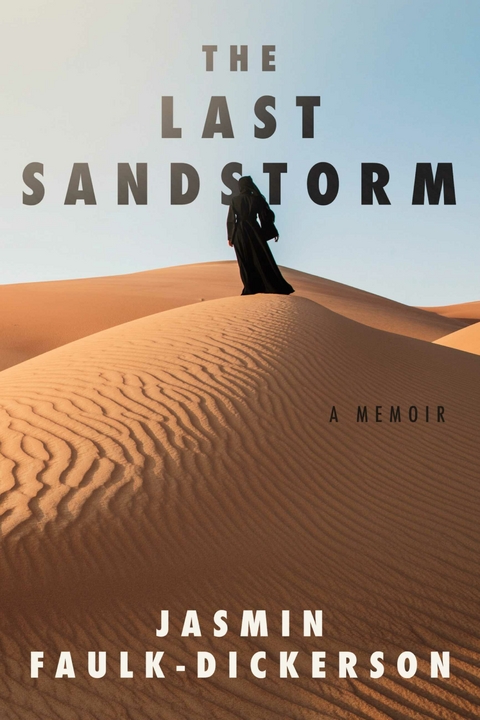

Last Sandstorm (eBook)

226 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-2928-9 (ISBN)

In her memoir, "e;The Last Sandstorm"e;, Jasmin Faulk-Dickerson tells the story of her first 25 years in Saudi Arabia, before her daring escape to the West. The author was born in the 1970's and grew up in the shadow of Riyadh, a city that was burgeoning into economic modernity, a sharp contrast with its archaic treatment of women. This memoir is both a coming of age story and an immigrant's saga, two overlapping narratives that are told with generosity, humor, and a pervasive sense of longing and loss. The narrative documents what it means to grow up with unanswered questions, strive to conform and belong, and finally, dare to leave behind a family, a country, and a way of life-the known world. In turn, Faulk-Dickerson invites us to take measure of our own potential and to participate fully in our own lives. While Jasmin experienced the privileges and privations of being female in a conservative Muslim regime, she survived and thrived by daring to imagine an entirely different kind of life. Jasmin shares the particulars of her daily life-school, Muslim customs, popular culture, family life, friends-that create a palpable sense of what it was like to be loved but also thwarted by circumstances. Out of sight of the censors, Jasmin became an aficionado of popular culture, drawing on music, dance, film, and TV icons from Europe and the United States. In the privacy of her bedroom/studio, she became an artist, performer, and feminist freedom fighter-a magnificent leap of faith that eventually translates into the courage to leave.

Logic Does Not Exist

October 10th, 2018.

I began the fall quarter of graduate school and sat in class consumed by the thoughts of my ill father far away. After seven weeks in the hospital, the news I dreaded to hear arrived. My brother called to tell me that our father had passed away. The last year or so of his life, his body endured the many challenging consequences of a lifetime of little self-care and poor habits. In childhood, I learned how to measure his level of stress through his moods and degree of consumption, whether it was smoking a pack a day or drinking beverages I was not allowed to taste. My father was an artist, troubled by the creative force within him, and by the confines of his culture, which amputated the limbs of his passion and intellect. The last time I saw my father was in 1999. When he died, the last thread of attachment to a country that gave me little to hold on to, was cut. But with his passing, I began to re-evaluate everything about his identity and mine. I became preoccupied with developing an understanding of who my father was, beyond who I thought he was.

Born in the very young, and recently founded Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, my father grew up in the northern part of the country, the city of Hail, in a mud house built by his father and older brothers. Later on, he recalled being old enough to participate in the expansion of the house and used his hands to build walls and rooms of mud. His childhood home was a striking slice of Arabian history and of tribal progress. When I visited New Mexico for the first time I was stunned by the uncanny similarities between the adobe homes in this Southwestern state and my father’s hometown in a desert thousands of miles away. When my father died, the only other place that seemed fitting to celebrate his life was, in fact, Albuquerque, even though he had never set foot in the United States.

My siblings and I reunited privately and quietly in remembrance of our father. We rented an adobe home within walking distance of the old town Albuquerque, and when we were not going through photographs of our father, or recalling childhood memories, we were walking through the streets and alleys of this town that made us feel closer to our father than we, perhaps, ever did during his life on his land.

My father was educated by intellectuals and teachers in meetings that were nothing like schools today. He spent a few hours daily learning from these masters how to read and write, and soon he was nominated for an upgraded program for gifted students, where he would study to become a teacher of the upcoming batch of eager Saudi boys. His teachers realized he had the X factor, and, after observing him in the classroom for a few years, the Saudi government chose him as one of a handful of students to be sent abroad on a full scholarship where he would be trained and educated, eventually becoming part of the first generation of Saudi professionals. He was the youngest, but also the first and only in his immediate family—conservative and humble—to obtain a full education. My father was somewhat of a wallflower, and I knew very little of his childhood and life. I learned about him in bits and pieces, either through accidental comments he dropped that revealed some of these details or through what my brother would report he learned from the elders.

My father’s mother, Nura, birthed him in the late 1930’s; she survived the birth, when many women didn’t, but her health was frail, and she was unable to breastfeed him. His older brother, presumed to be about twenty-five years his senior (birth certificates did not exist in those days, and we do not have exact documentation of births and deaths from back then), was married. His wife, Alya, had just delivered her second child, and without hesitation took on the role of nursing my father, her brother-in-law, as well. This was a story my father told in a short sentence, “I owe everything to ummi Alya,” (ummi my mother, in Arabic). His own mother, my grandmother—whom I never met—passed away when my father was in his mid-twenties. I sensed a deep sadness when he occasionally mentioned her, but his loss was soothed by the presence of the other mother in his life, who, after all, was the woman who fed him when he was an infant and gave him hope for survival during a time when many infants died of malnutrition and disease, including some of his own siblings. “Don’t forget to kiss her head,” he would remind me of the way elders are greeted, a gesture that he never failed to display with Alya. I wanted to view her as the paternal grandmother I never had, but an unexplainable resistance on her part made it clear I was to address her as my uncle’s wife.

I asked my father questions about his childhood: His response came in the form of a partial shy smile, eyes lost in thought, and I was left to create a biography of the man I idolized but knew so little about. How did a traditional Saudi boy go from living in a small premodern town, to becoming the man I knew growing up: educated, multi-lingual, stylish, and worldly. My father was a puzzle of many small pieces that sat mixed in a box. At every pivotal moment in my life, I attempted to piece together some of those odd shapes in order to understand him and feel closer to him. No matter how hard I tried to assemble the whole picture, I had to settle with fragments of the mystery that was my father.

He was a kind-hearted man; dare I say innocent and naive in many ways. His heart was pure, and his intentions were always good. He was mild tempered and soft spoken. In fact, these observations stem from the fact that I don’t recall ever seeing my father angry when I was a young child. He was instinctively affectionate. Hugs and kisses came to him naturally, and he displayed similar genuine affections towards animals. It would seem as though he was the perfect man and perfect father, and while in many ways he was, there were certain crucial elements that were missing. The culture he grew up in and the family he was part of taught him to be reserved and highly concerned with the opinion and approval of others. This was a huge struggle for me later on in adolescence, when I began to have ideas and ambitions, only to be dismissed by my father’s strong sense of societal responsibility and cultural obligations. When I was a preteen, I asked him if I could take horseback riding lessons, and without making eye contact, he said, simply, “Those activities are for people that want to show off, and that is not who we are.”

Who were we? Identity seemed to be a character that never changed its costume, no matter how many different scenes or plays it appeared in. Everything revolved around one’s identity, and yet, there was no room for developing it. There was a default standard by which one could measure and present their identity, achieved by conforming to social practices, dress-code, and self-imposed boundaries. This was my life in Saudi Arabia.

My father was the only member of our family with a native identity. As a child, I created in my mind, based on reality and imagination, many identities of my father: Papà, king, architect, teacher, businessman, brother, husband, boss, employer, son-in-law, Saudi, Italian…and priest. When he traveled outside of Saudi Arabia because work sent him around Europe or when vacation called for him to visit the Italian in-laws, my father wore western clothes, usually a suit, but on occasion casual slacks and a buttoned-up shirt. In Saudi Arabia, at home, he wore a “thobe,” the traditional long dress men wear. Outside the home, he wore a thobe, and a “ghutra,” the white headdress many Arab men, in the Arabian Peninsula, wear. Now and then, while on vacation in Italy, he would wear a thobe indoors, for comfort. One summer, while staying on the beach of Jesolo, not far from Venice, in Italy, my father stepped out on the balcony of our nineth floor condo in his thobe; within minutes, a crowd below gathered and stared at this mysteriously mystic priest-like figure. My father, not at all a social clown, surprised me with his response to the comical attention he was receiving. He raised his arms in the air as if offering benediction to all who watched. I was a very amused nine-year-old.

In fourth grade, when I started writing with ink, I was proud to use a pen which had my father’s business name printed on it. It was a maroon pen with blue ink. My father was the founder and general manager of his architecture and furniture store. His relationship with Italy began when he was a student and continued when he became a businessman. He traveled several times a year with his rich Saudi clients, some of whom were members of the royal family, to select the latest furniture designs from the exhibits in Milan, as well as other European cities like Zurich, Geneva, Paris, and Frankfurt. Some of his clients had children who were friends of mine at school, and I beamed with pride when I saw them writing with pens advertising my dad’s business. My father was a rock star! I felt especially important when I would—almost daily—call him at work to ask him random questions. It was an excuse to say, “Can I speak to Abdulaziz?” when the operator answered the phone. My father was very patient, and with his sweet murmurous voice he would say, “Wait till I get home,” after I would insist, “Can I take some gum from your room?” I didn’t care about the gum as much as I cared to have his attention. I wanted the person answering the phone to know I was his daughter. I felt excited when they would ask, “Who’s calling?” because it meant that I got to brag about being Abdulaziz’s daughter, but also because I was conducting business like an adult.

In the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 19.4.2022 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-2928-9 / 1667829289 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-2928-9 / 9781667829289 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 772 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich