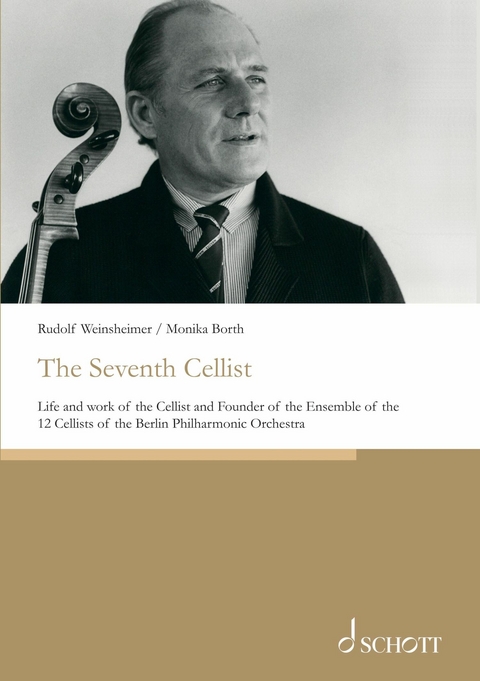

The Seventh Cellist (eBook)

161 Seiten

SCHOTT MUSIC GmbH & Co. KG / Schott Campus (Verlag)

978-3-95983-634-0 (ISBN)

A Wartime Childhood

To tell a life takes a lifetime – if you have tried hard enough to be truthful and fair to your memory. I have therefore tried to layout some sort of line, along which to proceed to include the essential points and markers, which were to determine my path and direction in life. In my early years these were both the element of music, as well as the strong relationship with my father, who had seen my talent and fostered it.

I was born on a July morning in 1931 in Wiesbaden. My mother singing and my father playing the viola, left an imprint even before my birth. And, looking at the horoscope, the stars must also have been “favourable” at my birth, leaving me with qualities typical of “Cancer“, including emotional awareness and artistic talents. However, I would not then know the importance music would assume during my adolescent years, nor the level of protection and comfort, which it would provide me later on.

I was born the second of five children. Marie-Theres was the eldest, and after me there were three more siblings: Klaus, Irmgard and Peter. My father was the viola soloist at the National Theatre of Wiesbaden and directed several men’s choirs in the Rheingau region. My mother was a kindergarten teacher who had given up work after her marriage, as was common in those days. She loved singing and had a wonderful voice! While doing her housework, she was often carried away by her singing, which added a new dimension to the room. For example, she sang the Ave-Maria with a passion that touched me deeply. With Händel’s solemn Largo however, her work at our kitchen stove was no longer important! Sometimes we children stood right behind her, copying her singing practices, open-mouthed and mimicking her gestures. It seems to me today that our mother’s singing was her way of distancing herself from us children, which, of course, we must have found confusing. This is how I see it today.

My father often accompanied my mother on the piano. Overall, music was very important for my parents’ marriage. All of their children, except for Irmgard, played an instrument. Marie-Theres, the eldest, learned to play the piano. But now it is my turn.

Margarete Weinsheimer, 1930

One day, when I was eight years old, I was playing “Klicker“ with my friends in front of the house. This is a game where you roll marbles on the ground, and when a special one touches a glass ball, the marble belongs to you. Suddenly I saw my father coming along the street, carrying an object covered in a case under his arm. I became curious a bit suspicious, and indeed, shortly afterwards he called me from the first floor window, “Rudolf! Come upstairs immediately!“ When I entered the room my father pointed to the string instrument before him, explaining, “This is a half-sized cello. Try it out!“ Even though it was smaller than a normal cello, made especially for children, the sheer size of the instrument somewhat intimidated me. Also, I had no idea how to start playing it. I was puzzled!

“Sit down“, my father said, putting the cello in front of me right between my knees and across my shoulder. I took the bow and stroked it across the strings a few times, which seems to have convinced him, “You make a beautiful tone, and you will be a cellist!“

From then on he spent one hour a day teaching me the instrument. He showed me how to hold the bow, how to find one’s focal point by keeping your arm in the right position and how to move the bow with your whole arm across the strings, while at the same time putting the fingers of your other hand on the strings. He watched me patiently and gave me advice when I got too tense.

Gradually, I discovered how to elicit melodious, well-sounding tones from the instrument. In my father’s eyes, I had now advanced into the community of musicians. There is a saying that to be recognized for one’s talents is bliss, and in looking back, I am grateful to my father for having seen my talent early on and for supporting me accordingly. Alas, during those days of early childhood, I quite often missed going outside and playing Klicker with my friends.

Soon afterwards, my father looked for an experienced cello teacher who could seriously teach and coach me. It was Miss Härtel, an elderly lady living in Rheinstrasse, about 15 minutes from our house, whose cello playing finally convinced him. This is when I started to learn about scales, finger exercises and practice, and intonation.

Her apartment was huge, but when I sat there and played, there was only the cello and I, and the strict eyes of my teacher. Some time later we began practicing Goltermann’s Cello Concerto in G-major, a well-known and popular concerto for students.

One day, as I was heading to my lesson, my cello on my back, some soldiers – it was the year 1939 - were standing on the pavement, smiling and asking me, “Where on earth are you coming from with this giant guitar?“ Never short for an answer, I replied self-confidently, “I am coming from a concert tour!“ This was supposed to be funny, but, in hindsight, I tend to think that perhaps even then I had an intuition about where my path would eventually lead me.

At that time, war had already started. Often, my father took my sister and me to visit hospitals, in order to play for wounded soldiers; I remember playing Beethoven’s Gassenhauer Trio and also the Goltermann Concerto. This was the first time I experienced a sense of stage fright, even though our audience were far from being critical. I told my sister, “In case I get lost somewhere, please continue with your part, I’ll find my way back in!“ When this did happen once, though, I did not find my way back in so quickly. Theres played on and on, until my father pushed her aside and took over the accompaniment on the piano. I felt very sorry for her, because she cried bitterly. However, she never blamed or reprimanded me for it!

Like all other boys, I had to join the “Hitlerjugend“, Hitler’s Young Boys’ Group. The cello, however, provided an excuse from the usual drills like exercising and parading. I was joined by two young violinists and a viola player, all of similar age, and we performed as a string quartet before high-ranking party members visiting town. We played Mozart’s Eine kleine Nachtmusik and smaller pieces by Schubert. Afterwards we were ‘promoted’ and received a lace, and later on a star to be put on our boys’ uniforms, which made me proud at the time. Today, of course, it reminds me of a very cynical and deadly context: For us boys, the star meant a badge of honour, for others it was to be a symbol of death.

On the annual “Day of House Music”, in which a selection of children attending Music Schools were allowed to perform, I was playing the Goltermann Concerto, together with my sister on the piano, and we were awarded First Prize. That was in 1941, when I was ten years old.

In the same year, I attended Gutenbergschule, a secondary school in Wiesbaden, where I played cello in the school orchestra and – on special occasions – performed as a soloist in our Assembly Hall.

At that time the bombing of big cities had already started. Almost every night, the sirens were wailing, and my mother took us five children, and we ran to the nearest cellar. My father stayed in bed, he did not seem to be afraid. One night, upon our return from the cellar, we saw a house split in two – the front wall was no longer there, opening up a view into all the apartments: we could still see furniture in living- and bedrooms. With each new siren, we were frightened and afraid that our house had also been hit.

But we were children at that time and were looking for adventure in the chaos. After these bombing nights, we did not have to go to school the next morning, an opportunity for my friends and me to roam the streets and collect splinters from grenades, which we would exchange with other schoolmates. The bigger a find was, the more precious it was.

While writing down these notes, I realize how I tend to look at these events from a naive child’s perspective, rather than focusing on the brutality of these happenings. Of, course, I feared for my father who had remained in the apartment. Was it really fearlessness or did he want to lead by example and help us calm down? I believe, after such an experience, a residue of fear will stay on in children. When, from one moment to the next, your familiar, trusted world can be entirely destroyed, what else is there to do than to enjoy playing with splinters of grenades!

The Weinsheimers in Wiesbaden, 1942

During the war, we were lucky to be in Wiesbaden, because unlike Mainz, on the other side of the river Rhine, Wiesbaden suffered only minor hits. While almost the entire inner city of Mainz had been bombarded, two thirds of Wiesbaden remained undestroyed. Today it is assumed that Wiesbaden was spared from bigger bombardment, because the U.S. Military had wanted to set up their quarters in the city. Whether this is true or not is not clear. However, it is a fact that, by the end of the war, the city had become the Headquarters of the Senior Command of the U.S. Air Force.

I was 12 years old when my mother told me one day, “Rudolf, I have read in a magazine that there is a special school for very gifted pupils in Frankfurt, and I have immediately registered you there.“

Frankfurt? Hardly where I wanted to go!...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.12.2021 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Ahrensburg |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Schlagworte | 12 Cellists • Autobiography • Berlin Philharmonics • Cellist • Cello • music • musician • Rudolf Weinsheimer |

| ISBN-10 | 3-95983-634-1 / 3959836341 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-95983-634-0 / 9783959836340 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich