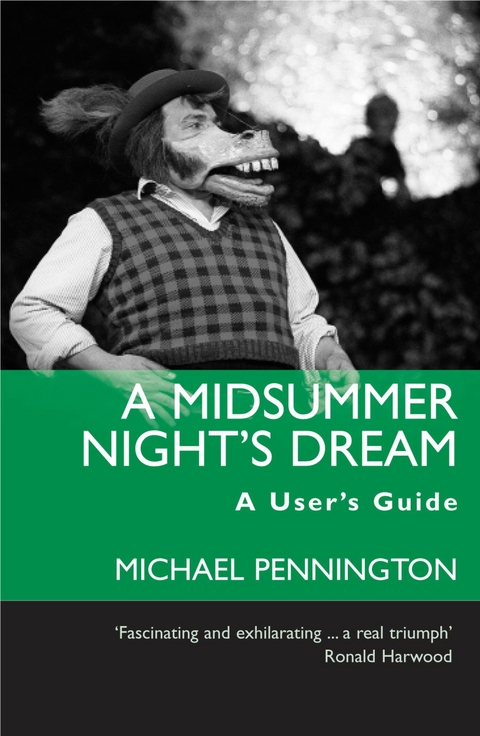

Midsummer Night's Dream: A User's Guide (eBook)

283 Seiten

Nick Hern Books (Verlag)

978-1-78001-763-1 (ISBN)

Michael Pennington is a British actor, director and writer. He has played a variety of leading roles in the West End, for the Royal Shakespeare Company, for the National Theatre and for the English Shakespeare Company, of which he was co-founder and joint Artistic Director from 1986-1992. He has also directed several of Shakespeare's plays, and is the author of books on Hamlet, Twelfth Night and A Midsummer Night's Dream, amongst others. He has toured his solo shows, Sweet William and Anton Chekhov, throughout the world.

An intensely practical account of how A Midsummer Night's Dream actually works on stage. A scene-by-scene guide to Shakespeare's best loved comedy, from the well-know actor Michael Pennington, drawing on his own experience of directing A Midsummer Night's Dream at the famous Open Air Theatre in Regent's Park, London, in 2003 - described by London critics as 'a captivating Shakespearian experience' (Guardian) and 'riotously funny and genuinely touching' (Telegraph). Praise for Michael Pennington's User's Guides:'An insider's guide par excellence' Simon Callow'He is sharply intelligent, scrupulously careful, hugely knowledgeable and, above all, wonderfully readable' Peter Holland, The Shakespeare Institute'It is his range of knowledge - along with a gift for writing clearly and memorably - that makes him such a fine guide'TLS

Michael Pennington has played a variety of leading roles in the West End, for the Royal Shakespeare Company, for the National Theatre and for the English Shakespeare Company, of which he was co-founder and joint Artistic Director from 1986-1992. He has also directed several productions of Shakespeare's plays, including Twelfth Night and A Midsummer Night's Dream.

ONE

Act 1 Scene 1

Until they speak, they could be dots on a barely glimpsed horizon; Theseus, who negotiated the labyrinth, and Hippolyta, the capture of whose famous magic girdle was one of the twelve labours of Hercules. But as they approach they shrink rapidly to human size, collaborating pleasantly like well-matched musicians. Their call and response seem to belong less to the world of gods and heroes than to the rituals of courtship, one voice fervent and the other appeasing: perhaps their grand names are disguising familiar transactions. First, the impatient bridegroom:

THESEUS: Now, fair Hippolyta, our nuptial hour

Draws on apace; four happy days bring in

Another moon. But O, methinks, how slow

This old moon wanes! She lingers my desires . . .

– then feminine reassurance:

HIPPOLYTA: Four days will quickly steep themselves in night;

Four nights will quickly dream away the time . . .

Hippolyta seems to be in tune with the natural rhythm of the seasons: she knows that even Theseus, for all his heroic interventions, cannot stop the world turning at its own speed. He can neither delay nor hurry the moment when

. . . the moon, like to a silver bow

New bent in heaven, shall behold the night

Of our solemnities.

Interpreting Shakespeare is a disreputable business: you must always be looking for trouble, especially when the surface seems smooth. So, like prospectors, we start turning these ten elegant lines over and over, inspecting them for negatives. For instance, did Hippolyta’s final ‘solemnities’ perhaps fall a little heavily on the ear?1 Would Theseus have preferred to hear something like ‘ecstasies’?

The sober word also halted a line of verse, leaving it short of a couple of beats. These days actors have been trained to spot this sort of detail and identify it as something other than convenience. The best advice is: if a speaker stops short in this way and the next character’s half-line supplies the missing beats, the cue should be sharply picked up; but if the next line is of full length, it should be preceded by a silence roughly equivalent to what was missing. This will create a moment quite heavy with meaning, as if the engine had suddenly stalled: it is not often in the prodigal flow of Shakespearian verse that a character falls silent for lack of anything to say.

In this case, Theseus adroitly picks up his cue and moves on, so he has covered up any awkwardness; but his tone has changed a little. He turns to a trusted officer with a slightly ridiculous order; compulsory pleasure for all. Philostrate must singlehandedly generate a holiday spirit, particularly among the young people; he is to

Stir up the Athenian youth to merriments

and

Awake the pert and nimble spirit of mirth.

Just as ‘solemnities’ sounded, well, solemn, ‘merriments’ and ‘mirth’ seem a little forced. To boost the cheerfulness, alliteration is called in:

Turn melancholy forth to funerals;

The pale companion is not for our pomp.

We are still wondering about Hippolyta: if it is true that she lowered the temperature, there must have been a reason. Theseus’s passionate impatience had just been expressed in a striking phrase: as the moon moved gently towards their wedding day, it reminded him of

. . . a stepdame or a dowager

Long withering out a young man’s revenue.

That is to say, when a second wife or widow gets hold of a father’s wealth, the son can’t get his hands on it. So to Theseus, counting down the days to being united with his bride feels like waiting for a rich relative to die. Was this quite the note to strike? A coarse little cluster of images surrounded his idea: stepdames and dowagers can’t help sounding like crones, and ‘withering’ underlined the ageism. Hippolyta, who has a less effortful way with language, elegantly improved on the charmless simile: to her, the moon irritating Theseus was as beautiful as a silver bow in the sky. Her stylishness, concluded by ‘solemnities’, might have added up to a mild reproach, and Philostrate’s mission may be a fast recovery from it.

Philostrate receives his instructions wordlessly, excluded from the self-conscious duet, but the actor needs to have a discreet attitude to them all the same; incredulity perhaps, banked well down behind professionalism. Theseus meanwhile, turning back to Hippolyta, moves smoothly through another gear-change into plain speaking, a certain toughness pressing behind the music:

Hippolyta, I wooed thee with my sword,

And won thy love doing thee injuries.

What kind of romance is this? Hippolyta is, it seems, not an equal partner but a prisoner of war. In the manner of certain men, Theseus believes that her affection was provoked by aggression: after all, as an Amazon, she is a soldier herself. But he also knows he owes her something, in ‘another key’. To marry her now

With pomp, with triumph and with revelling

will be considerate, and surely make up for his earlier lack of finesse. He is using the pompous word ‘pomp’ for the second time in five lines; Hippolyta wouldn’t use it once. And she never confirms whether an enormous wedding party – rather than good behaviour in the future – will be to her taste, because there is a sudden interruption.

One man’s theory is another’s nonsense: none of this interpretation may be ‘true’ in the sense of piously divining Shakespeare’s ‘intentions’. Words change their overtones over time; the temperaments of interpreters differ. We try to catch what Shakespeare might have meant, but there is sometimes much to be gained from going our own way, taking him forward with us rather than peering back across the centuries. And the fact is, this exchange started with the silvery moon and ended with a naked sword.

The man who bursts in unannounced, ‘good Egeus’, starts by routinely wishing his ‘renowned Duke’ happiness – so the man who killed the Minotaur and then turned into an anxious fiancé now has a Renaissance honorific as well. We are safe and sound in a familiar theatrical world. If Theseus is having trouble organising a marriage, it is nothing compared to Egeus, for whom the question has led to something far worse, a horribly insubordinate daughter. This is Hermia – a shock for the scholars in the original audience, by the way, since Hermia was a famous whore in antiquity much loved by Aristotle. Here she could only be that in her father’s mind: for us she is about to become a heroine.

Egeus’s unceremonious arrival forces a director to consider the practical context. Is this a normal thing to do in Theseus’s world? Are there guards? Is this a big public gathering, or something smaller, like an open hour or levée when the ruler receives plaintiffs? Or perhaps Egeus is presuming on his position as one of the great and good to break in on a tête-à-tête. Theseus’s reply:

Thanks, good Egeus. What’s the news with thee?

is inconclusive; ‘thee’, friendlier than ‘you’, but no more of a welcome than ‘thanks’. We are free to choose.

Regardless, Egeus takes the floor. Perhaps he has some legal training, that badge of the establishment: we suddenly seem to be in a courtroom. He has brought with him both client and accused, who have presumably agreed to the arbitration, and are now identified for Theseus and for us:2

Stand forth, Demetrius! . . .

Stand forth, Lysander!

Seemingly unstoppable, Egeus will combine lucidity with passion, as if he knows he has one chance only to make his points.

His interpretation of events is that while Demetrius has proceeded with old-fashioned correctness in securing his consent to marry Hermia, Lysander has gone a devious way to achieve the same thing. Lysander has been candid only with Hermia herself, sending her a comically impressive variety of trinkets, poetic billetsdoux and love-tokens –

EGEUS: . . . bracelets of thy hair, rings, gauds, conceits,

Knacks, trifles, nosegays, sweetmeats . . .

– and he has also, cutting a somewhat medieval figure, sung songs beneath her window. All these young man’s tactics can suggest to their seniors insincerity rather than its opposite – particularly if they have forgotten their own courtships. As far as her father can see, Hermia’s head has been turned as surely as if she had been given drugs (nowadays it would be that as well). He has been quite unnerved by all the sexual directness; it is affecting his language, so that it is Hermia’s ‘bosom’ Lysander has ‘bewitched’, and he obsessively refers to her as ‘my child’ – three times, and twice within three lines – as if Lysander were up to something illegal as well as undesirable. Presumably, had the more socially adept Demetrius done the same thing, Egeus would have found a different word for his daughter, such as ‘young woman of good judgment’.

Egeus’s speech, the least equivocal in the play so far, has a powerful swing to match the paranoid force of its feeling. It is hyperbole with blood racing through it, full of the furtive suspicion that a man’s womenfolk should be locked up as tightly...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.6.2016 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton |

| Literatur ► Lyrik / Dramatik ► Dramatik / Theater | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Theater / Ballett | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturgeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Account • Analysis • directing • Drama • Exercises • how-to guide • Performance • performing • Practice • Shakespeare • techniques • textual analysis • Theatre • Theatre Studies • Writing |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78001-763-4 / 1780017634 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78001-763-1 / 9781780017631 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich