Why The Liberation Struggle?

Where history is not recorded in print or on stone, or otherwise memorialized for the ages, it disappears. The oral tradition only works as long as the witnesses to the events under consideration are still among the living. I had the good fortune to have been a witness to, and participant in the post-World-War-II liberation struggle by Caribbean people toward statehood, and toward a more profound sense of African and indigenous pride and heritage denied us by slavery and colonialism. We sought to better the lot of our people who had resided as mere cogs in the wheels of Western development and industrialization, producing natural resources such as oil, bauxite, sugar or bananas as the times and needs of our rulers demanded. Our own ability to produce technology and realize innovation in management and societal structure, were cramped by our lack of authority over our affairs.

Despite being holders of British passports, as well as loyal British subjects, we had no elected representatives in the British parliament, and our local parliament had only limited dominion over our internal affairs – with none over our foreign affairs. It was for those reasons I became part of that national liberation struggle.

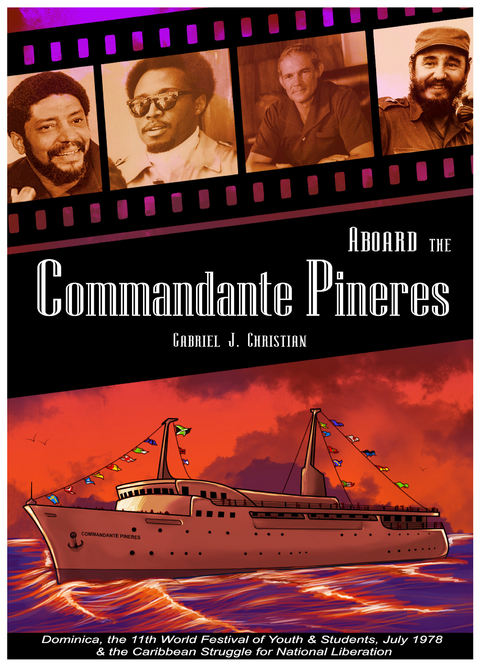

This work is a personal memoir from the inception of my political awakening. I date that awakening from 1970 and the mutiny of the Trinidad & Tobago Regiment during the Black Power surge in that sister nation, which caused much debate in our home. I recall the days of the Black Power movement; the Dread War; the return of Rosie Douglas and the independence movement; the trip to Cuba aboard the Commandante Pineres and meeting Fidel Castro; the rise and fall of the Grenada Revolution; the rise of Eugenia Charles to power and the Operation Red Dog invasion plot to unseat her; my departure for the United States, and what followed afterwards, to include the untimely deaths of Prime Minister Rosie Douglas and Pierre Charles. Finally, I will discuss the efforts we have made in the mobilization of Dominica’s overseas communities to aid the development process on the island.

* * *

The natural orientation of human beings tends towards freedom. In that respect, Caribbean people had a great history of rebellions against slavery and agitation in the cause of self-government. Jamaica had gotten Universal adult suffrage in 1944; Dominicans got the right vote in 1951. A semblance of democracy – at least the right to vote - was something that had come to the ordinary Dominicans only ten years before I was born in January 1961. The Caribbean of my generation was one in which change was hurtling along.

By 1959, the Cuban Revolution had taken place. That event was one of the most dynamic political changes ever to take place in human history. Under its gifted leader Fidel Castro, Cuba was to arise from the role of mere casino and tourist playground to a perch of respected leadership among the newly emerging nations.

With the advent of the Cuban Revolution, illiteracy was abolished, the savage fissures of race and class in a former slave state were lessened, and workers and peasants were given a place at the table of nationhood. The role of the Cuban Revolution in awakening Latin American and Caribbean people of my generation to their disabilities and to the possibility of another path forward to social justice and development was unparalleled. Even the United States was compelled to alter its foreign policies as a result. No longer was the Latin American/Caribbean region an untended and forgotten “backyard.” Rather, the people of that region gained a new voice in their affairs, demanded greater democratization amongst the political classes, demanded better health and education models, and demanded access to economic power. By 1962, U.S. President John F. Kennedy had initiated the Alliance for Progress to ensure that those needs of the majority of the Latin American and Caribbean people were met.

By the 1970s, the uprisings against the brutal Portuguese oppression of Africans in lands such as Angola, Guinea Bissau, and Mozambique gained our attention. We held marches and raised funds for the liberation movements in those countries. Additionally, we demanded the release of Nelson Mandela and for an end to apartheid before it became popular around the world. In the Caribbean, we were the first to protest against apartheid at an international forum, when British West Indian Federation Minister of Social Welfare, Dominica born, Phyllis Shand Allfrey, led a walk-out of the West Indian delegation to the International Labour Conference in Switzerland in 1960. Allfrey, born of an aristocratic local white family, had become a Fabian socialist during her time in London and had been associated with Aneurin Bevan and the left wing of the British Labour Party. Together with local Emmanuel Christopher Loblack, she founded the Dominica Labour Party in 1955.

The socialist advocacy of Allfrey, alongside that of trade unionist Emmanuel Christopher Loblack, was part of the foundation that radicalized my generation. Dominicans had long fought for freedom; the Carib natives had fiercely resisted colonization and enslaved Africans had fled the plantations on the island for the mountains in great number. Dominicans, therefore, had a long history of political activism, to include strident calls for Universal adult suffrage and self-government by the free colored leaders in the 19th and early 20th centuries. By the end of World-War-II, those calls for self-determination were surging across the Caribbean.

Dominica’s Phyllis Shand Allfrey, politician and author (1908-1986); a Fabian socialist and writer in London and active in British Labour Party circles before and during World-War-II, she returned home to found the Dominica Labour Party alongside trade unionist Emmanuel Christopher Loblack. She was the Minister of Social Welfare, and only female cabinet member, in the short lived government of the British West Indian Federation (1957-1961).

The first local to serve as Chief Minister of Dominica was Frank Baron. From Portsmouth, Baron was a successful businessman and fruit exporter. His time in office will be remembered for bringing Dominica into the British West Indian Federation, and starting the building of the Princess Margaret Hospital and Dominica Grammar School. Baron’s Dominica United Peoples Party, associated with the commercial and planter elite, was defeated in the 1961 general elections.

When the socialism inclined Dominica Labour Party took office in 1961 under agriculturist and poet Edward Oliver LeBlanc, opportunities for high school and college education expanded. The ordinary Dominicans now had a greater pride in their heritage, and a sense of nationalism soared.

Frank Andrew Merrifield Baron (1923-2016) was Dominica’s first Chief Minister (1959-1961).

Edward Oliver LeBlanc (1923-2004), Dominica’s first Premier and the architect of self-government and associated statehood.

Emmanuel Christopher Loblack MBE, (1898-1995) mason, trade unionist, and politician was the father of the Dominica trade union movement and co-founder of the Dominica Labour Party.

I was born on January 1, 1961 to Wendell M. Christian (1921-2011), fireman, and Alberta Christian, then a housewife and Red Cross volunteer. Our parents were hard working, of firm Christian faith, and ran the home with a firm no-nonsense approach. I had three brothers - Wellsworth, Lawson, and Samuel - and three sisters - Christalin, Esther, and Hildreth. Over time Christalin, the first of my siblings, showed evidence of developmental disability, and was taken out of school, where she had faced abuse. She became our mother’s constant companion at work, church, and play; she showered us with love and care when we were younger. All my other siblings went on to excel in professional accomplishments - Wellsworth became the first Dominican-born Chief Veterinary Officer; Lawson became a Civil Engineer; and Samuel became a General Surgeon. Among the girls, Esther became a Certified Public Accountant and Hildreth become an Environmental Scientist. Our parents drilled the importance of education into our heads with a relentless passion.

The Christian family at Delices, Dominica in 1947, the year Wendell Mckenzie Christian returned from his World-War-II Service in the British Army (Courtesy Henckell L. Christian, Gatecrashing into the Unknown (SPAT Press, 1993).

We did not grow up in a vacuum. A radical intelligentsia had erupted from the urban educated classes to which my family belonged. Our father, Wendell Christian, was born in 1921. His upbringing was nourished on the warm embers of Victorian era conservatism and the principles of thrift, education, and a strong Christian faith. The Christian family had its roots in Antigua. Both my father’s parents, William Matthew Christian and Beryl Christian (nee Jones) came from Antigua to Dominica in 1918. William Matthew was an officer in the Leeward Islands Police Force and was responsible for Dominica’s eastern district for many years. He was a kind policeman, and a skilled guitarist, whose good deeds benefited his eldest son Henckell Christian later in life. Due to the noble reputation earned by his father, who with integrity and respect for the locals, policed the eastern district of LaPlaine, Rosalie, Petite Savanne, and Victoria – as well as his own good work as an elementary school principal - Henckell Christian never lost an election in the east.

Our family in 1972. Front...