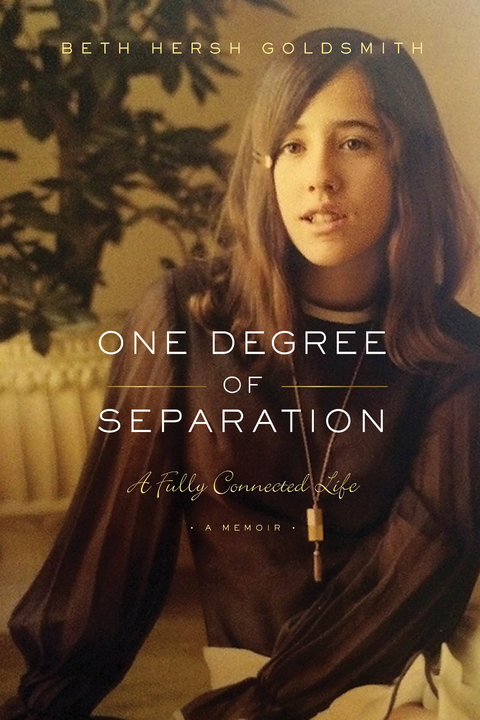

One Degree of Separation (eBook)

200 Seiten

Small Batch Books (Verlag)

9781937650735 (ISBN)

Born after all of her grandparents had passed away, Beth Hersh Goldsmith always felt she had missed out on hearing the rich tales of her family's previous generations. Grateful for her full and fulfilling life, she felt determined to share her own stories. In One Degree of Separation she recounts her eventful childhood in Charlotte, North Carolina, suburban Chicago, San Diego, and Beverly Hills. She tells of remarkable and surprising encounters with friends, relatives, and strangers in places as far-flung as Jerusalem, Soviet-era Leningrad, London, and Bulgaria. She shares the lessons of a rewarding career running nonprofits while raising a beautiful family. Most of all, she shows us the value of forging deep, human bonds with everyone from corporate CEOs to car mechanics, from nurses to neighbors to nannies. As Beth puts it, "e;Making these connections makes life meaningful."e;

THE NEW GIRL(WITH THE BROKEN ARM)

WHEN THEY DECIDED TO leave San Diego, my parents had two priorities: education and community. They wanted good schools for Andy and me, and they wanted our family to be in a Jewish community. That led them to Beverly Hills, where they rented an apartment on South Elm Drive. Beverly Hills was unlike anywhere I had lived: the affluence and the hyperawareness of financial status took getting used to. New acquaintances would immediately ask my address. I’d wonder, Why do you need to know where I live? Are you coming to visit? Of course, they were trying to size me up. As soon as they discovered that I lived on the south side of town, in the “flatlands,” in an apartment, no less, they knew there was nothing exciting to come and see at my house—no screening room, no fountains, not even a pool.

When I arrived at Beverly Hills High School for my junior year in the fall of 1973, I knew exactly two people: a boy I’d met and dated at USC’s debate camp that summer, and his sister, who was in my class. But I have never been accused of being shy. I didn’t hesitate to approach classmates and introduce myself, so I connected almost immediately with a group of friends, most of them residents of the south side of town. Those classmates became my friends for life. Decades later, we still talk and get together.

Though I found it easy to make friends, what shocked me was how competitive the school was academically, especially compared to my San Diego high school, Patrick Henry, where I had been the third-ranked student out of more than 1,200 pupils. At Beverly people paid more attention to the rankings and I just made it into the top ten percent of my class.

The San Diego schools hadn’t even required final exams, so I was nervous for my first round of finals, in the winter of my junior year. My first final was in the PE class I had taken, Self-Defense. For the exam, we were to spar with a partner, and we had to defend ourselves using the methods that we had learned in class. When the time came for the test, I noticed that the room had hardwood floors with no covering.

“Where are the floor pads?” I asked the teacher.

“Pads?” she asked. “You think if you get attacked in the street, you’re going to have a pad?”

I understood her point, but still, I suggested, for safety’s sake there should be pads.

“Excuse me, Miss,” she replied, “I’ve been teaching this class for years and I don’t need your help.”

The attacker she had enlisted for the exam, we learned, was her boyfriend, a hefty, towering brute of a man. When he came at me—all five feet of me—he pushed me with such force that I fell hard onto my right arm. I didn’t even have a chance to demonstrate my newfound self-defense skills. I knew immediately I had broken my arm. I didn’t cry. I simply said, “Something’s wrong with my arm.”

The teacher showed little sympathy. “Enough with the drama,” she said.

But I knew. Five years earlier at Camp Minokemeg I had fallen off a horse and broken my left arm. That time, too, an adult tried to minimize the fall: the camp director didn’t want to take me to the hospital, but I told her the pain was excruciating. “I need to go to the hospital,” I told my teacher now. “I can’t move my arm.” We had been in Beverly Hills so briefly that I didn’t have a doctor yet. I convinced the teacher to take me to the closest emergency room, at nearby Century City Hospital. There, I learned that I was correct. My arm was broken.

The school had to notify my mother, and I’m sure the administrators assumed that my family would sue. After all, I had warned the teacher about the hard floor. But my parents were not litigious people. We had no lawyers in our extended family. The district asked my parents to sign a release, but I told them to sign only if the school district agreed to pay for everything. The school agreed.

My incident was the kind of story that tends to circulate quickly in high school. Even without the benefit of Facebook or Snapchat, I gained an overnight reputation as the girl who broke her arm in self-defense class. The recognition wasn’t without benefits. When I ran for senior class vice president, I won the election easily.

In high school I also joined the speech and debate team. Our team prepared and researched topics in depth and traveled nearly every weekend to tournaments across California. Beverly had a very competitive team. I also competed on the speech team in both extemporaneous and oratory competitions. The experience proved to be excellent preparation for the public speaking I would do in practically every job I had.

Speech class was also where I met Sarah Catz, who was my age but a grade ahead of me. We immediately became best friends, and remain so today.

I put my developing speaking skills to good purpose. Because I was a student leader, Beverly selected me to attend a leadership-development program in Washington, D.C. At the time, my parents were struggling financially and couldn’t afford to send me, so I went before the Beverly Hills City Council with a request that the city sponsor my trip to D.C. In exchange, I offered do some public speaking upon my return. I succeeded, and that visit to the nation’s capital helped plant the idea to return to Washington later in life to work.

In all, high school at Beverly was a very positive experience. I was there for only two years, but in June 1975, at the end of senior year, I was voted the student who had done the most for the school.

I always felt it was important to work. From a young age I wanted a sense of independence, and I knew that partly came from knowing how to earn money and taking responsibility. During high school at Beverly, I worked for a while at the Fine Arts movie theater in Beverly Hills. Over the holidays, I worked in the gift shop at Hillcrest Country Club. I also worked at Earl Scheib’s Auto Paint Shops’ corporate headquarters in Beverly Hills, answering frustrated customers’ complaint letters.

My most glamorous encounter came in my junior year, when we were still new to Beverly Hills and I worked at Tot Toggery, a store in Century City that carried children’s clothing and toys. The store had a stellar reputation, attracting a broad array of customers. One slow Tuesday night, my manager went on a dinner break, leaving me alone in the store. While she was gone, a customer arrived, a modestly dressed African-American woman who was wearing no makeup. She was with a young girl. The woman asked for assistance selecting outfits for her daughter and for another child. When she found an item she liked, she told me, “I really like this. I’ll take one in every color you have.”

Every color? I couldn’t understand why, and my instinct was to discourage her. “Are you sure?” I asked. “Do you really need that many?”

“You’re so sweet,” the woman said. “Would you mind playing with my daughter in the toy section while I shop?”

So I entertained her cute young daughter until I saw the woman was ready to pay. She approached the cash register with a giant pile of outfits.

“Are you sure you want all of this?” I asked, trying again to dissuade her.

“Yes,” she said, “I have another child at home.”

It took several minutes for me to ring up all the items on the register. “How would you like to pay?” I asked when I finished.

“I’ll write you a check,” she said.

“I need to see a couple forms of ID,” I told her.

She handed me the check, and that was when I saw her name: Diana Ross.

“May I see some ID, please?” I asked again.

She took out her wallet, and as she held up her license, an accordion of credit cards unfolded practically all the way to the floor. Looking at her driver’s license photo, I saw her in full makeup, and suddenly realized that I was standing in front of the Diana Ross, of Diana Ross and the Supremes.

“Oh, Ms. Ross,” I said. “It’s really an honor to meet you.” I started to apologize, but she stopped me.

“No, no, it’s okay,” she said. “You were very helpful, and my daughter thinks you’re so much fun.”

I still had to write down all of her information. I knew the address was correct, because a classmate at Beverly High lived close to her on Maple Drive. And then Ms. Ross went on her way.

After a while, the manager returned. “Was it quiet?” she asked.

“Mostly,” I said. “But I made one pretty good sale.”

I showed her the check, and the receipt. I didn’t bother to tell her that I had spent half of the encounter trying to talk Ms. Ross out of spending too much money. For that evening, I was happy to let her think I was a great saleswoman.

Lincolnwood, Illinois, mid-1960s.

The Hersh family before my bat mitzvah, Lincolnwood, March 1969.

My confirmation photo, Lincolnwood, 1972.

Marilyn (Mom), Andy, and me in Haifa, Israel, June 1969.

Sarah Catz, Andy, and me at Jo and Bernie Arenson’s...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 13.4.2016 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-13 | 9781937650735 / 9781937650735 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,6 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich