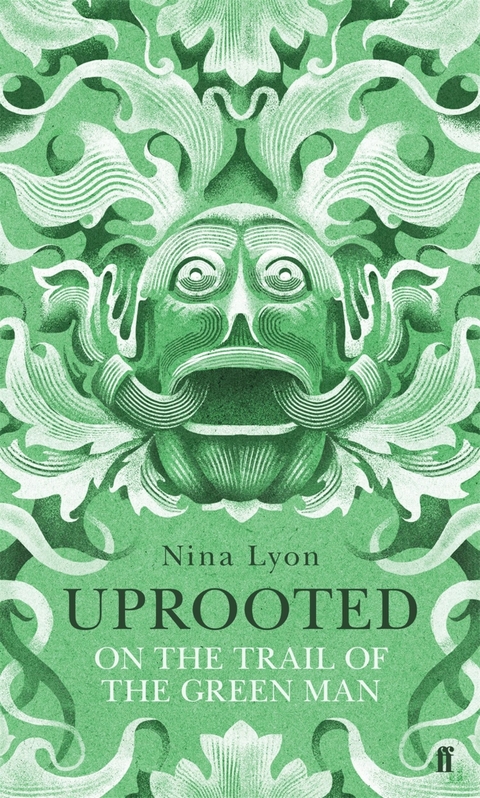

Uprooted (eBook)

320 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-31803-2 (ISBN)

Nina Lyon has worked in a Buddhist therapeutic community in Scotland, written contraband essays for cash in Berlin, and helps run the HowTheLightGetsIn philosophy festival near her home in Hay-on-Wye. Her essay 'Mushroom Season', inspired by youthful psychedelic misadventures and the mountains behind her home, was published by Random House in 2014 after being chosen as runner-up in the Financial Times/Bodley Head Essay Prize. She is currently completing a PhD about nonsense and metaphysics at Cardiff University.

Who, or what, is the Green Man, and why is this medieval image so present in our precarious modern times?An encounter with the Green Man at an ancient Herefordshire church in the wake of catastrophic weather leads Nina Lyon into an exploration of how the foliate heads of Norman stonemasons have evolved into today's cult symbols. The Green Man's association with the pantheistic beliefs of Celtic Christianity and with contemporary neo-paganism, with the shamanic traditions of the Anglo-Saxons and as a figurehead for ecological movements, sees various paths crossing into a picture that reveals the hidden meanings of twenty-first-century Britain. Against a shifting backdrop of mountains, forests, rivers and stone circles, a cult of the Green Man emerges, manifesting itself in unexpected ways. Priests and philosophers, artists and shamans, morris dancers, folklorists and musicians offer stories about what the Green Man might mean and how he came into being. Meanwhile, in the woods, strange things are happening, from an overgrown Welsh railway line to leafy London suburbia. Uprooted is a timely, beautifully written and joyfully provocative account of this most enduring and recognisable of Britain's folk images.

Nina Lyon has worked in a Buddhist therapeutic community in Scotland, written contraband essays for cash in Berlin, and helps run the HowTheLightGetsIn philosophy festival near her home in Hay-on-Wye. Her essay 'Mushroom Season', inspired by youthful psychedelic misadventures and the mountains behind her home, was published by Random House in 2014 after being chosen as runner-up in the Financial Times/Bodley Head Essay Prize. She is currently completing a PhD about nonsense and metaphysics at Cardiff University.

This quirky but engaging book describes Lyon's quest to track down as many examples of the [Green Man] as she can, on a journey that takes her from a Herefordshire church and Avebury in Wiltshire to the Black Forest, and from Gawain and the Green Knight to various festivals, meeting hippies and morris dancers along the way . . . Lyon is a witty and insightful writer and her account is infused with a self-deprecating charm.

What is most remarkable about Nina Lyon's stylish and eloquent book is the way she has mapped extraordinary things - ley lines, mythological figures, alchemy, magic - onto ordinary modern experience in a way that enhances in both directions . . . [it] is a major triumph which enables you to see the unfamiliar with new eyes.

Not only is it wonderful - sharp and beguiling and stuffed with the beginnings of tangents - but reading it together with my partner has been the strangest thing; an almost continuous sense of weird brought on by finding a book containing the same thoughts she and I have been discussing for a while.

What seems to be the white noise of the wind is, on closer listen, both polyrhythmic and multi-tonal. There is a single background hum and, weaving around it, the rise and fall of other winds: sidewinds and crosswinds and eddies. The house is on a hill, or, to be more precise, on the head of a ridge running off a hill into the Wye Valley. You can therefore, on a clear day, see down the valley in both directions, and across the valley to the Hergest Ridge and, behind it, the Radnor Hills, which are sometimes dusted with snow. Behind the house’s promontory is Little Mountain, which is not really a mountain, but a big hill.

You can see everywhere, and the wind can get everywhere. Perhaps because it comes from everywhere at once, channelled down the broad valley but refracted through many other places, it creates a cacophony, always altering, never resting. While the patter of windless rain is calming in its soft consistency, there is something rousing about the wind, which is not relaxing. It is like a restless chant.

It was after another white night of wind that I drove, sleep-deprived and in a condition not suited to adverse road conditions, along the length of the Golden Valley as it follows the path of the Dore down from the hills that loom above the Wye. The road was, in its better parts, a conduit for water flowing from one field to the next and, when it sloped, a waterfall. This was a good thing, for the movement of the water meant that it did not pool deeper. Red mud coursed along past abandoned cars left in last night’s floods, which had, for the moment, subsided. The static bodies of water were the scary bits, because you did not know where they would end. There were fewer of these, but the road had been carved away at its edges, which fell aside like glacial moraine, and the road, like the washed-out cars, looked fragile. An unremarkable journey alters when its success cannot be taken for granted. The water was winning.

We live in an age controlled by humans and human technology. One current assumption, the pessimist’s, is that human technology is so efficient and invulnerable that it will, eventually, kill off the planet. The optimists take a different line, which is that human ingenuity will evolve to solve all problems regarding human survival. Both rest on the assumptions that human ingenuity is unique, for good or for bad, and that human technology is more robust and powerful than nature. It took a month of angry storms to make me consider this more critically than before.

There was something about the surfeit and force of elements that made me want to go back to Kilpeck, which is where I was headed. I felt as though the aggressions of the weather might make more sense there, or perhaps that Kilpeck would make more sense in the light of the storms.

Kilpeck is a village in Herefordshire, about twenty miles away from my home near Hay-on-Wye. The village itself might have come straight out of The Archers, a westerly Albion of rolling hills and well-kept pretty cottages and a smart-looking pub with good food. At its edge are two noteworthy things: a motte-and-bailey castle and a church, which is not really, to my mind, a church in any conventionally understood Christian sense at all.

In the eleventh century, the parishioners of Kilpeck would have been trying to understand their landscape and the weather that altered it as an expression of a greater will. As human endeavour moulded the land, with clearings and mounds and buildings, so it was moulded by the land, existing in conflict, and in symbiosis, with nature.

Our rational belief in a mechanistic world of things enables us to find effective ways of operating in it, and our ways of operating in it further build that belief. We seem to be very adept at shaping the world to our will, and think little of the idea that the will and the ways of humankind might fall prey to any entity other than our own self-destruction.

But this sustained attack from untamed nature together with a big cultural wave of environmental doom-tales had made me question our narrative of human progress, our sense that comfort can be gained from our capacity to build and improve our world. It all seemed a bit anthropocentric. People looked small on stormy days. Once upon a time, the storms would have been attributed to a pagan deity of some kind, or an angry Old Testament God.

When I was seven, I was politely excused from Sunday school on the basis that being a vociferous atheist was fine but poorly suited to its aims – a gentle dismissal that leaves me with a residual fondness for the Church of England. I am not inclined towards religion, or superstition, or anything much that can’t reveal itself empirically.

I was not in a mood for finding God or redemption, or, for that matter, its pagan equivalent. I was interested more in how to simply understand a relationship with nature and the land in which both were considered to be alive, and not just alive but conscious. I wanted to get into what I had come to think of as the Kilpeck headspace. There is a sense of godliness revealed in nature that characterises the architectural decoration and, I would venture, would once have characterised the creed of the Kilpeck church. I was starting to wonder if taking a worldview which encompassed the idea of a will that is everywhere, whether of God or object or ether, might actually be a more practical way of understanding the things that modern-day scientism sometimes doesn’t.

The rain had stopped and the wet road, lit up in the first sunshine for weeks, glared its path to the village. The church stood, calm and flesh-pink in the new light, as though the storms had never happened. Behind it, through a yew-lined uphill avenue, the ditch around the castle motte had flooded into a moat, cutting it off apart from a foot of raised track. Rather than concealing the structure of the space, the water clarified its depths and heights and the even circle of the motte. Now that the rain had stopped and the sky was blue, its bright reflection shone in the flash moat.

Behind the castle tump, above the spiky tips of a pine forest, loomed the massif of the Black Mountains. Today the mountains were not black, but white with snow. As I drove back down the Golden Valley later, the snowline looked as though it were painted on in one vast stripe along the Cat’s Back. Birds sang from above the village. Beneath us, I thought I could hear a distant hum, or roar, and braced myself for revelation, but it was the A465.

The most famous thing about the Church of St Mary and St David at Kilpeck is probably the Sheela-na-gig carved among the corbels that encircle it. A woman baring her dilated vagina in an aggressive fashion is not the stuff we are led to believe that the Church, however early, is made of. But to see the Sheela-na-gig in isolation is to fall prey to our own post-Victorian prurience at such things – she sits in a line of extraordinary carvings of animals and men, song and dance and food and love that look like a pagan celebration of the stuff of life.

The Kilpeck Sheela-na-gig is seen as a warning against the sins of the flesh. It is true that, with her bald head and staring eyes, she looks bellicose rather than buxom, as though she’d glass you after a few drinks. But in the context of the other corbels it is very hard to see her as an aberrant warning against sin, because none of the others have that function.

As a point of comparison, the Abbaye d’Arthous is in the French Basque country, close to the Pyrenees, much in the same way that Kilpeck lies in the last flattish part of the Welsh Marches before they ascend into the Black Mountains. It was built at the same time, in the late twelfth century, and its corbels are similar in their Romanesque style and carving technique to those at Kilpeck. It is thought that the Herefordshire School of stonemasonry that graces Kilpeck and, somewhat less after desecrations and rebuilds, the nearby churches at Eardisley and Shobdon, consisted of a number of local craftsmen overseen by someone who had trained in France. There are, however, substantial differences in the subject matter.

The corbels at the Abbaye d’Arthous are clearly about the Christian conception of sin. There is a man either drinking from a barrel, or vomiting over it, as though the ambiguity links cause and effect. Adam’s modesty is covered with a fig leaf; a wolf seizes a lamb – it is sound biblical stuff. The corbels at Kilpeck include a Green Man presiding from his pillar across the main south entrance, two people either dancing close or getting amorous, someone playing a rebec as though warming up for a party, a number of animals – rams, pigs, fish, something like an armadillo – and, of course, the Sheela-na-gig. The Church that oversaw these could not have been the same in character as the Church that decorated the Abbaye D’Arthous.

And this is why the Kilpeck church had always intrigued me as a place, for how it showed how little we understand of the mindset of what must have been a fragmentary Church in the early Middle Ages, and how little we know of the old religions that pre-dated it. It takes the form of a church, and it is known and recorded as being one, but its character and location make it feel far more like a pagan site judiciously taken in by the Church.

It is easy, in an age of scandals deriving as much from its obsession with maintaining institutional face as from the endless abuses of power by sexually wayward priests and sadistic nuns, and conscious embrace of the AIDS pandemic for fear that women might gain bodily autonomy, to think of the Catholic Church as driven by a unified doctrine at all...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.3.2016 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Lebenshilfe / Lebensführung | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Weitere Religionen | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Ethnologie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | Folklore • H is for Hawk • Magic • Occult • Paganism • Robert Macfarlane • The Shepherd's Life |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-31803-7 / 0571318037 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-31803-2 / 9780571318032 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich