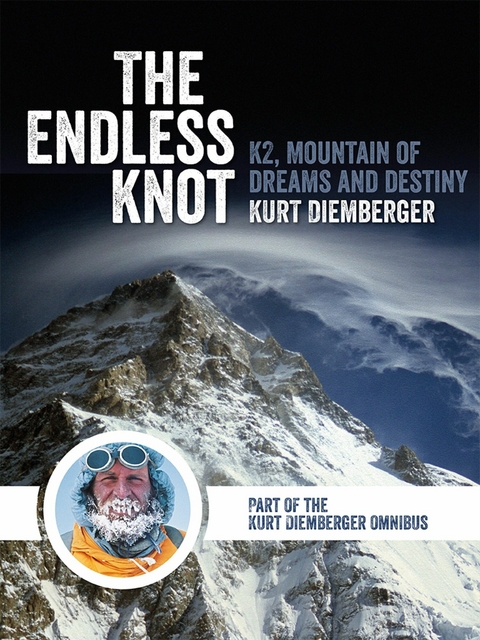

Endless Knot (eBook)

Vertebrate Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-910240-03-8 (ISBN)

'A monumental book ... I defy anyone to read it and remain unmoved.' Stephen Venables, Alpine Journal Acclaimed as one of the most powerful accounts of mountain adventure and tragedy ever written, The Endless Knot is a harrowing account of the 1986 K2 disaster. A rare first-hand account from a survivor at the very epicentre of the drama, The Endless Knot describes the disaster in frank detail. Kurt Diemberger's account of the final days of success, accident, storm and escape during which five climbers died, including his partner Julie Tullis and the great British mountaineer Al Rouse, is lacerating in its sense of tragedy, loss and dogged survival. Only Diemberger and Willi Bauer escaped the mountain. K2 had claimed the lives of 13 climbers that summer. Kurt Diemberger is one of only two climbers to have made first ascents of two 8000-metre peaks, Broad Peak and Dhaulagiri. A superb mountaineer, the K2 trauma left him physically and emotionally ravaged, but it also marked him out as an instinctive and tenacious survivor. After a long period of recovery Diemberger published The Endless Knot and resumed life as a mountaineer, filmmaker and international lecturer.

The Lonely Mountain

Thirty Years Earlier – On the Baltoro

with Hermann Buhl

Shshsht! Shshsht! Shshsht! Shshsht! Our snowshoes glide over glistening, sunlit powder, across ribs of ice and the gently rolling curves of the glacier.

Ahead of me, still pushing strongly despite fatigue and moving with short, precise steps, is the small, almost delicate figure of Hermann Buhl, his energy clearly visible as he covers the irregular ground of the Godwin-Austen Glacier. I can see his grey, wide-brimmed felt hat above his rucksack, his fine-boned hands resting on the ski-sticks for balance each time he raises one of the oval, wooden snowshoes to take another, sliding step, but the expression in Hermann’s ever-alert eyes as he scans the way ahead, I can only guess at. Thus, we make our way forward, past long rows of jagged ice-shapes, as if in an enchanted forest where everything has been frozen into immobility. Corridors between the towers lead us along the spine of the moraine, through freshly fallen snow.

We are alone – alone in the heart of the Karakoram, surrounded by mighty glaciers, in a savage world of contrasts, of ice and rock, of pointed mountains, granite towers, fantasy shapes rising a thousand metres or more into the sky, some very much more.

This spring (May 1957), besides Hermann and me and our three companions back in Base Camp, there are no other human beings on the whole of the Baltoro Glacier.

Marcus Schmuck and Fritz Wintersteller from Salzburg and Captain Quader Saeed, our liaison officer (who, having no one to liaise with, has been homesick for the more colourful life of Lahore for several weeks now), are fellow members of the only expedition this season within a radius of several hundred kilometres. We are alone on this giant river of ice, fifty-eight kilometres long, which with its fabulous mountains constitutes one of the remotest and most beautiful places on earth. Uncounted lateral glaciers fan out to peaks of breathtaking size and steepness – forming compositions of such harmony that they seem to emanate magic – to places where no one questions ‘Why?’ because the answer stands so plain to see. My great ambition, to go once in my life to the Himalayas and climb the highest peaks in the world, has been realised – at the age of twenty-five. Hermann Buhl invited me to join his team on the strength of my direttissima climb of the ‘Giant meringue’ on the Gran Zebru (Königsspitze), a sort of natural whipped-cream roll widely considered to be the boldest ice route in the Alps to date. I’m ecstatic. Everything I have, I will put into this one big chance.

Now, as we make tracks in the snow at almost 5,000 metres along one of the lateral glaciers (having set off from close to Concordia, the Baltoro’s kilometre-wide glacier junction), my thoughts turn to the early explorers. The glacier we are on is named after the cartographer Godwin-Austen, one of the first to set eyes on the Baltoro in the middle of the last century; but Adolf Schlagintweit was probably the first non-local to get close to the Baltoro area and to reach one – the western – of the Mustagh Passes (Panmah Pass). He has not been commemorated by any name on the map. On the other hand, the beautiful, striated glacier across Concordia from us is dedicated to the traveller G.T. Vigne, who never set foot on it. Martin Conway, leader of an expedition in 1892, was the first to come to the Karakoram to mountaineer; he was later knighted and a snow-saddle he discovered was named after him.

We are not explorers in the same sense as those men, yet on a personal level that is exactly what we are. Going into an empty landscape like this, among giant mountains, your heart quickens and the prospect around the next corner is no less seductive to you than it was to the first people who were here. The same silence dominates the peaks, the same high tension arcs from mountain to mountain; days can still seem like a true gift from heaven. So it is with us on this morning.

Above us soars Broad Peak. No man has ever climbed its triple-headed summit, which rises into the sky like the scaled back of a gigantic dragon. For me, the very rocks breathe mystery: nobody has touched them. I am happy that this mountain, one of the eight-thousanders, is the target of our expedition. But today, Hermann and I are heading off towards K2.

The tallest pyramid on earth seems to grow steadily before our eyes in its unbelievable symmetry. Many years ago, British cartographers[1] computed the height as 8,611 metres: 237 metres lower than Everest. The second highest mountain in the world is, however, considerably the more difficult of the two to climb and is without doubt one of the most beautiful mountains in the world.

The international expedition of Oscar Eckenstein, which included the Austrians Hans Pfannl and Dr Victor Wessely, made the first attempt in 1902 and managed to reach 6,525 metres on the North-East Ridge. But in 1909, a large-scale expedition led by the Duke of the Abruzzi opened up the South-East Spur (the Abruzzi Ridge or Rib), revealing that as the most favourable line of ascent. They only got to 6,250 metres, but on nearby Chogolisa (Bride Peak), the Duke and his mountain guides clambered to 7,500 metres, which stood as a world altitude record for many years. They were only 156 metres from the summit.

Hermann Buhl has stopped to look across towards Chogolisa, that shimmering trapeze of snow and ice, maybe thirty kilometres away. ‘A lovely mountain,’ he says.

To me, it looks like an enormous roof in the sky, but Hermann’s attention is already back with K2. ‘Such a pity that’s been climbed already! But wouldn’t a traverse be great; up the ridge on the left, then down to the right, by the Abruzzi?’ And he tells me all he knows of the Abruzzi route, how the mountain was first climbed this way by a huge Italian expedition three years ago. They put in no fewer than nine high-altitude camps. And, it’s said, fixed 5,000 metres of rope on the ridge itself. Ardito Desio, a professor of geology, was leader and the two summiteers among the eleven-man team were Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni. It was a national triumph, which threw the whole of Italy into a whirl of rejoicing. It is true that they used bottled oxygen, but it ran out towards the end. And they didn’t give up! Hermann is laughing, ‘So you see, it does work! You can do it without!’ Then he tells of George Mallory and Sandy Irvine, who never came back from a summit attempt on Everest in 1924, despite taking oxygen. Nine years after their disappearance an ice-axe was found at 8,500 metres which can only have belonged to one of them, yet today we are no nearer knowing whether they made it to the top of the world or not. And he tells of Colonel Norton, who went very high on Everest without oxygen, and of Fritz Wiessner, who got within almost 200 metres of the top of K2 in 1939, also without using it.

I can see from his animation, from his eyes and gestures, that Hermann can hardly wait to have a go at K2, without oxygen or high-altitude porters. ‘In West Alpine style’ is the phrase he coined for it. ‘Mmm!

K2 is a beautiful mountain and no mistake,’ he concludes, adding pensively, ‘and the way to do it is definitely up that left ridge, down the right.’

But the mountain looks so high, like nothing else in the world. We are only tiny dots before this huge mass, which shines like crystal from the snow and ice on its faces. It arouses no desire in me. I am happy with our choice: Broad Peak is still virgin, and almost 600 metres lower than K2. Better for our ‘West Alpine’ enterprise – already considered crazy by a lot of people – better than the second highest mountain on earth!

With that, my thoughts turn to ‘our’ eight-thousander: the only time it was ever attempted was in 1954 by a German expedition under Dr Karl Herrligkoffer. They found it pretty hairy. Following a line under constant threat from avalanches, the climbers discovered that huge blocks of ice had stopped only inches short of their tent. One day the Austrian Ernst Senn fell down a sheer 500-metre ice wall, whistling along like a bobsleigh to land (by incredible good fortune) safely in the soft snow of a high plateau. At 7,000 metres, icy autumn storms drained the men’s last reserves of energy, forcing them at length to abandon the attempt.

A few days ago, buried in the steep ice of the ‘Wall’, we discovered a German food dump with advocaat, angostura bitters, some equipment … and a three-year-old salami, which still tasted all right. There was even a tin of tender, rolled, Italian ham, a well-travelled delicacy which quickly found its way into our stomachs. I have to confess that this side trip we’re making to K2 is purely out of curiosity, to see what delicious titbits might still be lying around at the site of the Italian Base Camp!

A delusion: all our efforts to find the camp fail. The wide glacier is white and pristine, and there is no trace on the moraine either. Finally, we turn around and waddle on our snowshoes back the way we came.

It was curiosity, too, that led us to penetrate the avalanche cirque of Broad Peak. Hermann wanted to take a look at the route Herrligkoffer had chosen. The doctor had been his leader on Nanga Parbat and there was no love lost between the two men. Hermann himself had opted for a more direct line on the West Spur of Broad Peak, a line of greater difficulty, it’s true, but very much safer, and one that had been recommended by the well-known ‘Himalayan Professor’, G.O. Dyhrenfurth. A straightforward and direct ascent like this is much more in Hermann’s style.

As we approach Base Camp, tired now from dragging these legs with their...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.8.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-910240-03-6 / 1910240036 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-910240-03-8 / 9781910240038 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich