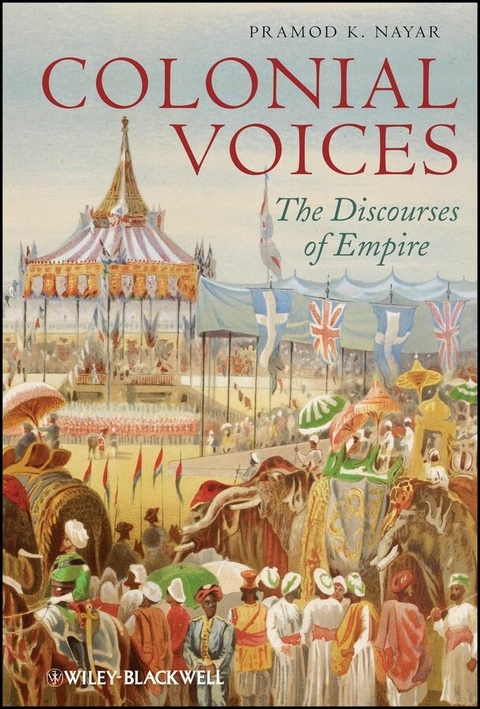

Colonial Voices (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-27897-0 (ISBN)

- An engaging examination of European colonizers’ representations of native populations

- Analyzes colonial discourse through an impressive range of primary sources, including memoirs, letters, exhibition catalogues, administrative reports, and travelogues

- Surveys 400 years of India’s history, from the 16th century to the end of the British Empire

- Demonstrates how colonial discourses naturalized the racial and cultural differences between the English and the Indians, and controlled anxieties over these differences

Pramod K. Nayar is a member of the English Faculty at the University of Hyderabad, India. He has been Smuts Visiting Fellow in Commonwealth Studies at the University of Cambridge, the Charles Wallace India Trust–British Council Fellow at the University of Kent at Canterbury and Fulbright Senior Fellow at Cornell University. His many publications include States of Sentiment: Exploring the Cultures of Emotion (2011), An Introduction to New Media and Cybercultures (2010), Postcolonialism: A Guide for the Perplexed (2010), English Writing and India, 1600–1920: Colonizing Aesthetics (2008), and Writing Wrongs: The Cultural Construction of Human Rights in India (2012). Forthcoming is a book on new media.

This accessible cultural history explores 400 years of British imperial adventure in India, developing a coherent narrative through a wide range of colonial documents, from exhibition catalogues to memoirs and travelogues. It shows how these texts helped legitimize the moral ambiguities of colonial rule even as they helped the English fashion themselves. An engaging examination of European colonizers representations of native populations Analyzes colonial discourse through an impressive range of primary sources, including memoirs, letters, exhibition catalogues, administrative reports, and travelogues Surveys 400 years of India s history, from the 16th century to the end of the British Empire Demonstrates how colonial discourses naturalized the racial and cultural differences between the English and the Indians, and controlled anxieties over these differences

Pramod K. Nayar is a member of the English Faculty at the University of Hyderabad, India. He has been Smuts Visiting Fellow in Commonwealth Studies at the University of Cambridge, the Charles Wallace India Trust-British Council Fellow at the University of Kent at Canterbury and Fulbright Senior Fellow at Cornell University. His many publications include States of Sentiment: Exploring the Cultures of Emotion (2011), An Introduction to New Media and Cybercultures (2010), Postcolonialism: A Guide for the Perplexed (2010), English Writing and India, 1600-1920: Colonizing Aesthetics (2008), and Writing Wrongs: The Cultural Construction of Human Rights in India (2012). Forthcoming is a book on new media.

Acknowledgments vii

1 Introducing Colonial Discourse 1

2 Travel, Exploration, and

''Discovery'': From Imagination to Inquiry

12

Imagining Multiple Worlds: The Fantasy of

''Discovery'' 18

The Narrative Organization of Discovery 29

''Inquiry'' and the Documentation of

the Others 41

Conclusion: ''Discovery'' and Wonder,

''Contracted and Epitomized'' 49

3 The Discourse of Difference: Constructing the Colonial

Exotic 55

The Colony and Imperial Wealth 57

The Exotic in English Culture 59

The Colonial Exotic: Aesthetics, Science, and Difference

60

The Sentimental Exotic 62

The Scientific Exotic 79

Conclusion: From the Indian to the Colonial Exotic 95

4 Empire Management: From Domestication to Spectacle

104

The Domestication of Colonial Spaces 106

Administering Colonial Spaces 121

''Raising the General Credit of the

Empire'': The Spectacle of Empire 140

Conclusion: Imperial Improvisation and the Spectacle

145

5 Civilizing the Empire: The Ideology of Moral and Material

Progress 161

England's Age of Improvement 164

Discipline and Improve 170

Imperial Lessons 174

The Salvific Colonial 178

Rescue, Reform, and Race 183

Conclusion: From Improvement to Self-Legitimization

194

6 Aesthetic Understanding: From Colonial English to Imperial

Cosmopolitans 201

The Self-Fashioning of the Scholar-Colonial 204

Antiquarian Aesthetics and Colonial Authority 213

''Consumption, Ingestion, and

Decoration'': Colonial Commodities 219

The ''Empire City'': Pageantry and

Empire 226

Conclusion: From Colonial English to Imperial

Cosmopolitan 229

References 235

Index 260

"Nayar makes the field of 'colonial discourse studies' irresistible

to anyone seeking to explore the complex relationship between

textual production, (South) Asian Orientalism, and the politics of

empire building."

- Walter S. H. Lim, National University of Singapore

"Drawing on an enormous range of writing, Dr. Nayar provides a

lucid and nuanced analysis of British representations of India as a

continent to be discovered, controlled, 'civilized',

and incorporated. This important book by one of India's

leading scholars gives students and scholars a significantly new

understanding of the complex nature and history of colonial

discourse regarding India."

- C.L.Innes, University of Kent

"A theoretical and historical perspective on colonial

discourse...an impressive demonstration of the nature and power

of discourse using an array of texts from the archive of British

India."

- Nandana Dutta, Gauahati University

Chapter 1

Introducing Colonial Discourse

Considering those travelers before me had few of them been in those parts where I had been, or at least not dwelt so long there, I venture to offer some novelties, either passed over by them, or else not so thoroughly observed.

(Fryer 1698)

It was impossible to contemplate the ruins of this grand and venerable city, without feeling the deepest impressions of melancholy. I am, indeed, well informed, that the ruins extend, along the banks of the river, not less than fourteen English miles.

(Hodges 1990 [1793]: 117)

What the learned world demands of us in India is to be quite certain of our data, to place the monumental record before them exactly as it now exists, and to interpret it faithfully and literally.

(Prinsep 1838: 227)

The Bengalis seemed infinitely to prefer literature, law, and politics to anything that required some physical as well as mental exertion … When I introduced gymnastics, riding, and physical training in the colleges, they heartily accepted these things, and seemed quite ready to emulate Europeans in that respect.

(G. Campbell 1893: 273–274)

The Indian servant is a child in everything save age, and should be treated as a child: that is to say, kindly, but with great firmness.

(Steel and Gardiner 1909: 2–3)

John Fryer, writing in the seventeenth century when the English East India Company was still a trading company seeking rights and routes, seemed desirous of conveying to his fellow countrymen the uniqueness and “novelties” of India. Fryer was writing when much of India had not quite been “discovered” by the English, and hence his anxiety to unravel the vast territory's mysteries. By the time William Hodges wrote his account, the English had settled into both trade and local politics, and their attitudes toward all things Indian were beginning to ossify. Hodges rejects India as just another ruined civilization. If Fryer sought to convey awe, Hodges hopes to invoke pity for the wonder that was India. James Prinsep, writing a few decades after Hodges, saw his role as a faithful historian-archaeologist, who would offer authoritative interpretations of the country through a compilation of data that mapped India's difference from other places. George Campbell announces to his countrymen that the moral and physical improvement of the indolent and effeminate race of Indians is possible through sport and discipline, while Flora Annie Steel and Gardiner caution the English on how best to deal with the Indian—as somebody childlike, weak, vulnerable, gullible.

In each of these extracts we find a particular image of the colony and the natives being produced: the undiscovered, mysterious India; the ruined civilization; a vast and varied Indian culture; the morally degenerate Indian and the childlike Indian. This is not an exhaustive sampling of the ideas, attitudes, and approaches that the English internalized and exhibited toward its greatest colony, India, nor does it hope to cover the enormously diverse and diffuse set of representations of Britain's other colonies, or other European colonies. But even this short inventory indicates the sheer plenitude of such representations about India. This variety of representations, in which India is projected, presented, analyzed, and evaluated, constitutes the subject of the present book—representations that are found in a corpus of colonial texts dating back to the 1550s. These texts were produced even as colonial discoveries, battles, conquests, administration, domination, and renovation proceeded from the 1580s till roughly the mid-twentieth century. It is within these texts and representations that we can find embedded and expressed the attitudes that informed and influenced the practices of colonial rule.

Colonialism was a process by which European nations found routes to Asian, African, and South American regions; conquered them; undertook trade relations with some of the countries and kingdoms; settled for a few centuries in these places; developed administrative, political, and social institutions; exploited the resources of these regions; and dominated the subject races. Colonialism was characterized by military conquest; economic exploitation; the imposition of Western education, languages, Christianity, forms of law and order; the development of infrastructure for a more efficient administration of the Empire—railways, roadways, telegraphy; and the documentation of the subject races' cultures (history, ethnography, archaeology, the census). While military, economic, and political processes are central to the colonial process, the last item in the catalogue above—documentation of the subject races—has perhaps been the subject of the greatest volume of postcolonial studies since Edward Said's Orientalism (1978).

How the Europeans thought and wrote about their empires was the focus of Said's epoch-making work. Arguing from the premise that to represent the non-European culture was a form of colonial thinking, Said showed how literary, historical, anthropological, and other texts carried within them the same politics as those that inspired military and economic conquests. “Colonial discourse” is the study of these texts and representations. “Discourse” is here simply the conversations, representations, and ideas about any topic, people, or race. It is the context of speech, representation, knowledge, and understanding. It determines what can be said and studied and the processes of doing so. It is, in short, the context in which meaning itself is produced. Discourse is produced about an object by an authority possessing the power to make pronouncements on this object. The Asian nation or people or culture was the object about which the Europeans produced information, documentation, representations—discourses. Asians became the object of analysis, examined, categorized, studied, and judged by European writings about them. Asia became, thus, a field of study. In such a situation, the Asian need not have a say in how s/he might be studied. That is, the colonial discourse that constructed the Asian as an object of study did not account for the Asian's views or resistance, pleasure, or displeasure in the matter. Discourse thus flows one way: by the European about the Asian. It is in this one-sided flow of discourse that we can discern the power relations that mark colonialism. Colonial discourse masks the power relations between races, cultures, and nations. It makes the relations seem natural, scientific, and objective. Colonial discourse therefore produces stereotypes from within European prejudices, beliefs, and myths. Thus the myth of the effeminate Bengali male was a centerpiece of European discourses from the mid-eighteenth century. Over a period of time, this unprovable, prejudiced, and seriously questionable stereotype was treated as an objective description even by natives. Masquerading as philanthropy, the civilizing mission or scientific observations, these stereotypes and representations, enabled the Europeans to attain and retain power over the natives. As we can see, discourses of the effeminate native naturalized a myth, a stereotype, so that it passes as true knowledge or authentic observation. The power relations of colonialism do not allow for dissenting discourses (though they did exist, as we now know from the work of the Subaltern Studies Group). It rejected alternative opinions, views, and representations as inauthentic, inaccurate, or irrelevant. Thus only one discourse, that of the European, was allowed to dominate. Colonial discourse, therefore, plays a major role in the management of racialized imperial relations.

“Discourses” are not innocent reportage or fictions of the mind. They do not simply reflect an event or a person in the form of an image or a description. Discourses define and constitute the reality of that person or event for the viewer, listener, and reader. That is, it is impossible to know a person or event outside the representations of the person or event. Discourse is not reality, but it is the only means of accessing that reality. For example, to understand the magnitude of a disaster, we should have a definition, a frame in which disaster is measured. With this frame in our mind we perceive the events, and categorize them as a “major” disaster or a catastrophe. Discourse studies analyzes these frames through which we see the world, experience and understand it. Colonial discourse studies is therefore the study of the various kinds of representation through which the Europeans described, catalogued, categorized, imagined, and talked about Asians or Africans. It believes, after Said, that representations represent a form of textual knowledge of the non-European. Such a knowledge is a preliminary moment to colonial military or economic conquest.

Let us take an example here. When the British were planning an intervention in India's succession politics (in various kingdoms, notably Arcot in southern India and Awadh in the north) from the 1760s through to the 1850s, they began not with military conquest. Over a period of time the colonial statesmen and commentators built up a textual archive in which they demonstrated:

- the tyranny of the local monarchs;

- the pathetic state of the subjects;

- the chaos that would follow the succession battle.

Together, these representations became a set of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.2.2012 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Wirtschaftsgeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Asian & Australasian History • Colonialism & Imperialism • Geschichte • Geschichte / Asien u. Australasien • History • Kolonialismus u. Imperialismus • Literatur • Literature • Literaturwissenschaft • Political Science • Politikwissenschaft • postcolonial theory • Postcolonial Theory, Studies, Southern Asia History, British Empire, India, Imperial, dominance • Theorie der Postkolonialzeit |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-27897-6 / 1118278976 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-27897-0 / 9781118278970 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich