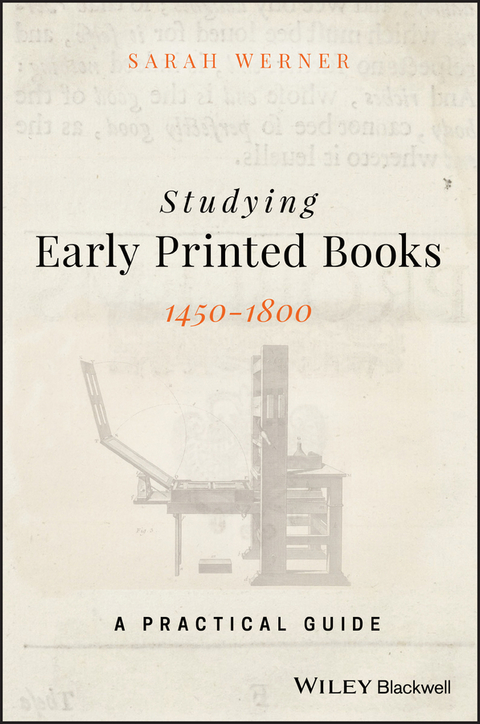

Studying Early Printed Books, 1450-1800 (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-119-04995-1 (ISBN)

A comprehensive resource to understanding the hand-press printing of early books

Studying Early Printed Books, 1450 - 1800 offers a guide to the fascinating process of how books were printed in the first centuries of the press and shows how the mechanics of making books shapes how we read and understand them. The author offers an insightful overview of how books were made in the hand-press period and then includes an in-depth review of the specific aspects of the printing process. She addresses questions such as: How was paper made? What were different book formats? How did the press work? In addition, the text is filled with illustrative examples that demonstrate how understanding the early processes can be helpful to today's researchers.

Studying Early Printed Books shows the connections between the material form of a book (what it looks like and how it was made), how a book conveys its meaning and how it is used by readers. The author helps readers navigate books by explaining how to tell which parts of a book are the result of early printing practices and which are a result of later changes. The text also offers guidance on: how to approach a book; how to read a catalog record; the difference between using digital facsimiles and books in-hand. This important guide:

- Reveals how books were made with the advent of the printing press and how they are understood today

- Offers information on how to use digital reproductions of early printed books as well as how to work in a rare books library

- Contains a useful glossary and a detailed list of recommended readings

- Includes a companion website for further research

Written for students of book history, materiality of text and history of information, Studying Early Printed Books explores the many aspects of the early printing process of books and explains how their form is understood today.

SARAH WERNER is a book historian, Shakespearean, and digital media scholar based in Washington, DC. Werner worked for nearly a decade at the Folger Shakespeare Library and has taught book history and early modern literature at numerous universities.

A comprehensive resource to understanding the hand-press printing of early books Studying Early Printed Books, 1450 - 1800 offers a guide to the fascinating process of how books were printed in the first centuries of the press and shows how the mechanics of making books shapes how we read and understand them. The author offers an insightful overview of how books were made in the hand-press period and then includes an in-depth review of the specific aspects of the printing process. She addresses questions such as: How was paper made? What were different book formats? How did the press work? In addition, the text is filled with illustrative examples that demonstrate how understanding the early processes can be helpful to today s researchers. Studying Early Printed Books shows the connections between the material form of a book (what it looks like and how it was made), how a book conveys its meaning and how it is used by readers. The author helps readers navigate books by explaining how to tell which parts of a book are the result of early printing practices and which are a result of later changes. The text also offers guidance on: how to approach a book; how to read a catalog record; the difference between using digital facsimiles and books in-hand. This important guide: Reveals how books were made with the advent of the printing press and how they are understood today Offers information on how to use digital reproductions of early printed books as well as how to work in a rare books library Contains a useful glossary and a detailed list of recommended readings Includes a companion website for further research Written for students of book history, materiality of text and history of information, Studying Early Printed Books explores the many aspects of the early printing process of books and explains how their form is understood today.

SARAH WERNER is a book historian, Shakespearean, and digital media scholar based in Washington, DC. Werner worked for nearly a decade at the Folger Shakespeare Library and has taught book history and early modern literature at numerous universities.

List of Illustrations vii

Acknowledgments ix

Introduction 1

Part 1 Overview 8

Getting Ready to Print 8

At the Press 16

Also at the Press 19

After Printing 20

The Economics of Printing 23

Part 2 Step-by-Step 26

Paper 26

Type 34

Format 42

Printing 55

Corrections and Changes 61

Illustrations 65

Binding 71

Part 3 On the Page 79

Advertisements 79

Alphabet and Abbreviations 80

Blanks 83

Dates 83

Imprint Statements 85

Edition, Impression, Issue, State, Copy 86

Initial Letters 88

Marginal Notes 90

Music 91

Pagination and Foliation 92

Preliminary Leaves 92

Press Figures 93

Printer's Devices 95

Printer's Ornaments 95

Privileges, Approbations, and Imprimaturs 96

Signature Marks 96

Title Pages 98

Volvelles and Movable Figures 100

Part 4 Looking at Books 102

Good Research Habits 103

Handling Books 104

Appearance 106

Contents 108

Page Features 111

Usage 113

Digitization 114

Part 5 The Afterlives of Books 118

Loss Rates 118

Catalog Records 120

Books in Hand 132

Books on Screen 139

Conclusion 149

Appendix 1: Further Reading 152

Appendix 2: Glossary 171

Index 180

Introduction

If you buy a book today at your local book store and enjoy it so much you want to share it with your globe‐trotting Aunt Sadie, you’d expect that the copy you buy online and have shipped to her will be the same book that you own. It’d have the same cover, the same number of pages, the same text on all those pages. But if you lived in 1573, and you bought a book at a bookstall near St Paul’s Cathedral in London, and then met up to discuss that book with a friend who had also bought a copy at the same stall, you might discover that your books looked very different. They might have different bindings, they might have different words on some of the pages, they might even not have the same number of leaves.

That difference between books then and books today is why this book exists. Everything that we assume about print today—that it is fixed, easily replicated, identical in mass quantities—are features that were gradually established during the first centuries of printing. In order to understand what an early modern book is and how printed conventions came to be what they are, we need to understand how early printed books were made. And so this guide describes the technologies and practices of hand‐press printing in order to help us identify how the mechanics of making books shapes how we read and understand them.

When Johannes Gutenberg created movable type and the printing press in the late 1440s and early 1450s, he was drawing on existing practices and technologies in metalworking and wine making and tapping into an established market for manuscript books and for woodcut prints. What Gutenberg set into motion was the ability to create a large variety of texts printed in large quantities; a 400‐page work didn’t need 400 different woodblocks to print it, but a font of type that could be arranged into different words and rearranged into different words for corrections and other books.

The technologies associated with Gutenberg—type cast from metal matrices, wooden press operated by hand, and black ink from oil and soot—remained largely the same until machines were introduced to the process in the early 1800s. The practices of how books were made and how they were sold changed over time, especially in the first 50 years of printing when many of the conventions we take for granted, like title pages, were still being developed. But how type was cast and books were printed remained essentially consistent until machines entered the picture. And so, although the period of hand‐press printing in the West stretches over 250 years and across Europe and North America, we can study its practices as a rough continuum. What you learn about how a book was printed in Leipzig in 1502 will be relevant for a pamphlet printed in Boston in 1784.

The focus of this guide is on printed works, but the distinction between print and manuscript is less strict than we have come to assume today. The development of the printing press happened alongside a growth in manuscript production; the increased availability of paper made both printing and writing on paper easier. The earliest printed books often depended on manuscript completion; the addition of initial letters and rubrication to mark the start of passages blur the line between printed books and hand‐written ones. Even later printed books worked hand in hand with manuscript practices, encouraging readers to write in corrections for print errors and users to copy out printed passages in their manuscript miscellanies (compilations of miscellaneous texts). The rise of print also meant an increase in printed forms designed to be completed by hand; indeed the earliest surviving printed works were not books but indulgences with blank spaces left for the purchaser’s name. David McKitterick’s Print, Manuscript, and the Search for Order, 1450‐1830 provides illuminating details and a historical framework for understanding why print and manuscript should be considered alongside each other. But an introductory book can only cover so much material. Since more readers encounter early modern works in their printed form, rather than in manuscript, and since reading early modern handwriting is a skill unto itself, this guide keeps its focus on understanding printed books. (If you’re interested in learning more about early modern manuscripts and paleography, see Appendix 1, “Further Reading,” for some resources.)

If print and manuscript are blurred categories, so is that of books. We tend to think of printing as making books and of books as printed objects. But there are plenty of printed works that are not in the form of a codex (the technical term for a gathering of leaves secured along one side—that is, the form of the book as we are used to it). Forms, pamphlets, playbills, proclamations, and news sheets are examples of early printed objects that are not books, but that are an integral part of the print trade. And there are plenty of codices that are not printed, in medieval and earlier periods and continuing through the early modern and modern periods. Manuscript bibles, books of poems, account books, miscellanies, and diaries are usually in the form of a codex. For simplicity’s sake, this guide describes our object of study as printed books, but the printing processes discussed here are true for any printed work in the hand‐press period, codex or not.

It’s also important to remember from the outset that we base our knowledge of early printed books on what has survived, but those survivors aren’t necessarily representative of what was being printed and read. Collectors have long had a bias toward books they deemed important and so literary works were saved at a much greater rate than almanacs. Some printed works were built for survival—those heavy bound bibles. Others were barely intended to last through the week—printed broadsides pasted to walls would disappear as soon as it rained, if not before. We work with what we have, but we can try to remember there’s a lot we don’t have. (For more on what survived and what’s missing, see “Loss Rates” in Part 5.)

But why do you need to know how hand‐press books are made or how to read them? Can’t you just pick up an edition of Utopia and be done with it? You certainly could. There are plenty of modern editions not only of Utopia but of many of Thomas More’s other works as well. But an interest in Utopia can easily lead to an interest in the humanist circles through which it moved and the various letters and poems and other material that preceded and followed early editions of the book. Such paratextual material, however, is usually appended to the end of a modern edition, if it’s included at all, while the early editions published some material before the main text and some after, and the first four Latin editions varied in what material was included and where it appeared. In other words, modern editions of this text don’t include all the information that an early reader would have seen and a modern researcher might want. And, of course, many other early printed books don’t exist in any modern edition.

There’s also information to be found in looking at a book’s original printing that can help us understand how it was used. Take a look at the title page in Figure 1, for example.

Figure 1 The title page to a 1616 edition of Colloquia et dictionariolum septem linguarum, often referred to as a Berlaimont (or Berlemont) after the original traveler’s vocabularies created by Noël de Berlaimont. Image made available by the Folger Shakespeare Library under a CC BY‐SA 4.0 license (STC 1431.86).

What strikes you about it? One of the questions you might ask—though it’s easier to notice when you’re holding it in your hand, rather than looking at a picture—is why it’s shaped so oddly. Books generally are vertical rectangles, taller than they are wide. This title page, however, is decidedly squat, perhaps one‐and‐a‐half times as wide as it is tall. Why does it look like this? And why is the title page so dense? You might also notice that there are three blocks of text on the page, rather than a clearly identified title and author as is usual today.

If you could hold it in your hand, you would see that it’s in an old leather binding with what look like broken clasps attached. The first couple of leaves of the book come before the title page and have handwritten notes on them, as do the last leaves of the book. And the printed text, which makes up the bulk of the 400 or so pages of the volume, is made up of seven columns of text in varying styles of print.

It’s a funny, repetitive little book, at first glance. But why is it so? If you can read the Latin, French, or Dutch on the title page, you will have already started to work out what this book is: it’s a dictionary with dialogues and vocabulary lists in seven languages. It’s squat in part because it has to fit seven columns of text across the page openings, one each for Flemish, German, English, French, Latin, Spanish, and Italian. It’s also squat because it’s meant to be a size you can easily carry with you and refer to as needed; that’s in part why it has clasps across the fore‐edge, to keep it closed and secure from damage when being carried. Imagine reading this in a modern edition (were a modern edition to exist): Would it be the same if it was shaped like our books usually are?

This...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 13.12.2018 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Design / Innenarchitektur / Mode |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | 16th Century English Literature • 18th century • Bibliographer • Bibliography • Bildungswesen • book binding • bookmaking process • catalogs • digital facsimiles • Digital Images • digital reproductions • Early modern • Early printed books • Education • Englische Literatur / 16. Jhd. • examination of the book process • Facsimiles • hand press books • historical framework of the printed book • How to make a book • Information & Library Science • Informations- u. Bibliothekswissenschaft • introduction to printed books • Literature • Literature Special Topics • Literaturwissenschaft • <p>Guide to early printed books • manuscript and books • overview of early printed books • paper and book production • plan of action to studying a book • practical understanding of early printed books • printing and book production • provenance</p> • rare books libraries • Renaissance • researching old books • Rubrication • Special Collections • Spezialthemen Literaturwissenschaft • study early printed books • studying early printed books • the steps of making a book • typographic elements • understanding early printed books • using libraries |

| ISBN-10 | 1-119-04995-4 / 1119049954 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-119-04995-1 / 9781119049951 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich