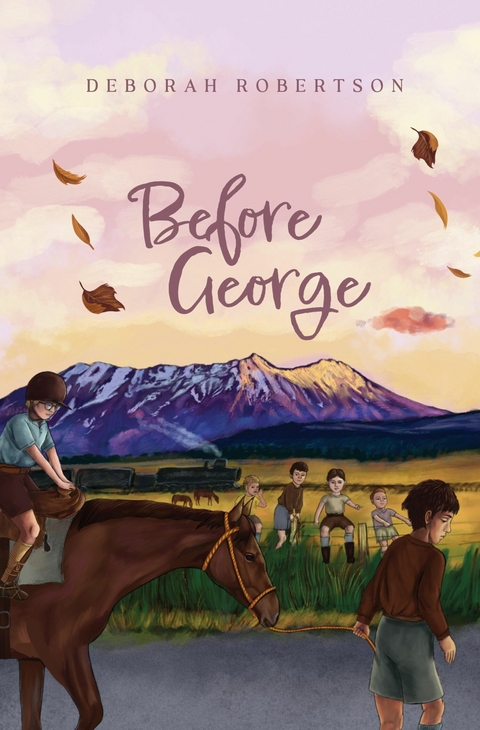

Before George (eBook)

416 Seiten

Huia Publishers (Verlag)

978-1-77550-792-5 (ISBN)

When Marnya immigrates to New Zealand from South Africa in 1953 with her mother and sister, her mother cuts off Marnya's hair and changes her name to George to hide her identity as a girl. Hours later, their Christmas Eve train plummets into the Whangaehu River and George loses not only her family and name, but also the answers as to why her mother deceived her father and fled their homeland. Now a ward of the state, George finds herself enrolled in a rural school where survival depends on fitting in with a group of boys who think she's strange. Disconnected from everything that once defined who she was, George must reconstruct her identity and cometo understand her mother's decisions.

Chapter One

My new name was George.

I traced the name across the cool surface of the window and said it aloud.

‘J-orge.’ The first consonant, a foreign sound to my Afrikaans tongue, cut the air. I looked across at my sister, Karen, but I hadn’t woken her. She was curled up like a kitten on the dull leather of the train seat, her red Christmas dress rumpled around her. Next to her sat my mother, hands folded across her lap, eyes closed. It angered me that she was able to sleep while I was left awake to wonder.

I wondered how easy it was going to be, having a new name. Did a new name make me a new person? For the past twelve, almost thirteen years – all my life – I was Marnya.

I was angry with Mama for bringing us here. I’d taken off my shoes, now that she wasn’t looking, and my long thin legs dangled over the seat. I had always thought of them as girls’ legs and girls’ feet. It was hard to think that they might also be boys’ legs and boys’ feet. What was it that made them one or the other?

I slid my finger down the windowpane. So cold. Everything was cold here – the houses of Wellington huddled into the sides of the hills as if hiding from the wind, the rough sea, the black rocks. It wasn’t fair. My mother couldn’t take my name away and make me someone else. She said it was only for a short while, but I didn’t believe her. She’d told me that us coming here was only for a short while, and now it was forever. I wished we had never got on that ship in Cape Town.

◆

‘You can’t be called Marnya in New Zealand.’ My mother stood before me, biting her bottom lip. She always did this when she was worried.

We were standing on the dock by the ship.

‘They don’t have names like that in New Zealand,’ she was saying, and her eyes flitted about, as if scared she might be overheard. ‘We’ll call you George instead.’

‘George is a boy’s name.’ We weren’t English but even I knew that. There was a boy called George at my school who spoke in a broken Afrikaans.

‘I know that. You’ll be a boy in New Zealand, just for a couple of weeks.’

A wave of confusion washed over me. In the world before this day, it had never occurred to me that anyone could be anything except the sex they already were.

At once my mother was a hundred times bigger and me a hundred times smaller. I heard my own voice, small and far away, exclaim, ‘What do you mean?’

My mother crouched down in front of me. ‘I don’t want anyone to recognise us,’ she said. ‘If you’re dressed as a boy then it makes it harder for anyone to track us down. Especially with our names changed.’

‘But I’m not a boy!’

‘Shh. Listen. It will only be for a little while. Just until we get to Uncle Ryl. Then we’ll sort it all out.’

‘But I thought we were only going for a month?’ This made no sense. Who didn’t she want to find us?

My mother said nothing. It was perhaps this more than anything that impressed on me the seriousness of this conversation. My bottom lip quivered and I gulped down the lump in my throat. ‘Mama?’

‘We’re never going back,’ my mother whispered. ‘Not ever.’

At once my world dissolved. The noise of the Cape Town port faded into a strange glugging. Voices, once near and imposing, now a thousand miles away. I understood that I had been told something important. Something I knew, deep in the dark pits of my heart, that even my father didn’t know.

‘We’ll get you a haircut,’ she said. ‘And some new clothes. Brand new ones.’

‘But what about my old ones?’

‘You’ve almost outgrown most of your dresses anyway. We’ll get you new ones when we move in with Uncle Ryl.’

‘I don’t understand!’ I exclaimed. Uncle Ryl had emigrated to New Zealand when I was seven, and I hadn’t seen him since. The only clear memories I had of him were of him teaching me to ride his pony.

‘You don’t have to understand.’ My mother’s arms clamped around my shoulders. Firm. ‘You just have to trust me.’

Her eyes were hard as baubles. I wanted to tell her, No. I wanted her to explain.

But the moment passed. My mother stood up and talked to a man on the docks about our baggage.

Two hours later, she cut off all my long hair.

◆

It was seven hours since we’d left Wellington. Restless, I stared at the window, but it was impossible to see the name I’d drawn on the glass. Was George real or just a ghost, easily erased by time?

I wasn’t sure. I knew only that I didn’t want him. Didn’t want his legs, his short hair, his khaki shorts. I wanted me.

Outside, the darkness was coal-black.

Then light erupted in the night and for a moment I saw trees, rocks, depth. Then it was gone.

I glanced back, unsure if this ghost light was real or not. The light flickered on again. A tunnel through the darkness. In it a man running, his torch the beam of light. He was waving his arms, his ghoulish face panicked.

The train tore past the man, and the world again

fell into blackness. Then the train brakes screeched, long and slow. In the cabin, a couple of people lifted their heads.

And then a roar. Building so quickly it consumed every other sound.

‘Mama?’ I said, my voice shattering at the edges.

The train leaped, twisting like a snake in mid-air. I was flung from my seat. The floor was a wall, the window the ceiling. I smacked into the man across the row from me. Heard him grunt when we collided. And then my feet were on the wall, my head on the floor. The seat slapped my elbow.

I yelled, but I had no voice. I could do nothing but move with the sound, my body tumbling over and over.

Water.

Cold water everywhere.

My hands wet. My hair wet.

It swirled under me, splashed over me. My body jerked. I lifted my head above the wave to find it almost filled the carriage. Then I was under again.

Darkness. My mother, her body long and bent, speaking to my father. Telling him we’d only be going to Cape Town for a week.

My father, sandals on the dusty sunburned earth. The lines of his face angry, taut. ‘You don’t need to see your sister!’

I was up again, head above water. My mouth gulped in gasps of air. There was no light. My eyes stung. I flailed my arms, the world revolving around me as I disappeared.

My mother in the garden singing a song that doesn’t quite make it to her eyes. She hangs out the clothes, checking for snakes in the long grass around the washing line.

I smacked into something hard. A tide was pulling at my body, sucking me into its liquid jaws. I pulled free. It dragged me down.

The tide changed, drawing me out from the carriage. A current pulled me away. I rose, pushing, scrabbling, a desperate burning for breath in my throat. I was suspended in the water with nothing but its lick on my skin to guide me.

The current pulled me to the surface, and I felt the bite of air. I opened my mouth to gasp a breath, but silt, silt on my face, choked me. A sharp stick jabbed one hand. I wanted to scream for help, but I couldn’t. I was moving rapidly, irreversibly, with the flow of water.

For a moment I was pulled under again. Something solid scraped beneath my feet. I pushed my toes in, but this pushed me forward, so I was like a swimmer in the current. My body slapped against a rock, air driven from my lungs. I clamped my arms around it, hugging it, holding it.

I wanted to see, but I did not want to see the water that swirled around me. For a brief second in my mind’s eye, I saw again the train as it stood on the platform in Wellington. The dark crust of its undercarriage. The lingering dampness of the steam. The image of it dissolved into now. To this world of darkness and water, and I wondered if I were dead.

It was some minutes before the water subsided. I was mostly on the rock, the current at my knees. I tried to move, but the surface was too slick. As soon as I lifted my arm, I slipped. The next thing I knew I was standing in the water, up to my thighs, the flow still pushing me against the cold stone.

I felt the bottom. My right foot was higher than my left, so I pushed myself that way. My feet crunched over branches, pushing them into the silt.

I reached the bank, slick with mud, and crawled up on my knees pricked by gravel. I skidded, blind and hunting for higher ground. I didn’t even try to stand, shaking too much. Instead, I crawled through sludge half-a-foot deep until my hands found firmer ground.

A wet clump of grass, slick and sharp, met my flailing hand and I grasped it, pulling myself higher. There was more grass and bracken, crispy beneath my knees. I sprawled into it, sobs escaping my mud-clogged mouth.

I didn’t know where I was. It didn’t seem important. All that mattered was the ground beneath me. The firmness of it. My breath was thick, heavy. I couldn’t get enough of it. A small dark tunnel closed in on my mind.

I awoke as part of the earth, my body frozen in a dry crust, the passages of my nose turbulent as I breathed in and out.

It took a moment for the stinging to set in. I’d been scraped and cut in a thousand places I couldn’t see.

I reached up with a hand, surprised I still had one, and pawed at my face. The muck around my eyes was thick, and when I finally blinked, fragments of dirt stung my eyes. I snapped them shut again and sat up on my haunches. Silt burned the inside of my nose. I pawed at my eyes again, blinking until the stabbing had dulled to a throb.

I was sitting in a patch of forest in the watery light of a moon. Beyond me lay a tide of mud that fell away to the banks of a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.10.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kinder- / Jugendbuch ► Sachbücher ► Geschichte / Politik |

| Schlagworte | 1950s New Zealand • Aotearoa New Zealand history • being an outsider • Coming of Age • Emigration • Identity • Tangiwai disaster |

| ISBN-10 | 1-77550-792-0 / 1775507920 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-77550-792-5 / 9781775507925 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich