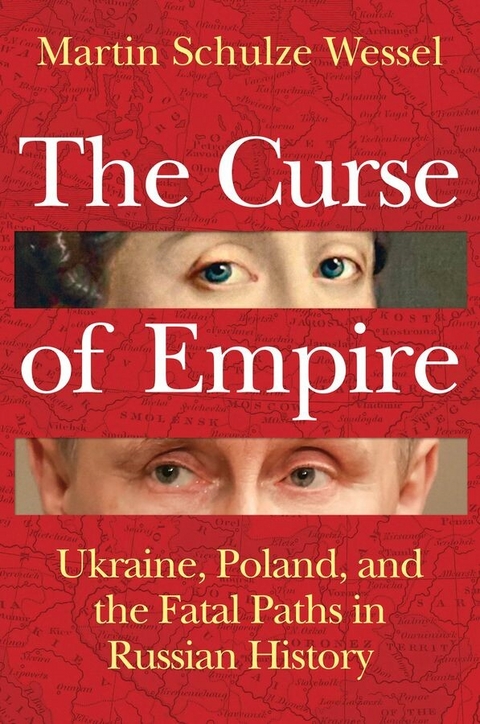

The Curse of Empire (eBook)

461 Seiten

Polity (Verlag)

978-1-5095-6400-2 (ISBN)

Russia's attack on Ukraine marks an epochal break in European and global history. Undoubtedly, the decision to go to war is closely linked to one person, Vladimir Putin, but Russia's war is not driven solely by one man's power calculations. We can only make sense of Russia's actions in Ukraine, argues the distinguished historian Martin Schulze Wessel, by putting them in the broader context of the history of Russian imperialism and the influence it continues to exert today.

Schulze Wessel argues that Russian imperialism was shaped by Russia's relationship to Poland and Ukraine. These states were absorbed or partitioned by Russia in the eighteenth century, but Russia's rule over them was contested both by the Poles and by the Ukrainians. The entangled history of these three states produced path dependencies whose impact is still felt toda. Poland and Ukraine share a common history characterized by Russian domination and Polish and Ukrainian resistance to it; just as the Polish question challenged the Russian Empire in previous centuries, so too does the Ukrainian question today. Schulze Wessel argues that, as a result of Russia's confrontation with the Polish and Ukrainian questions, Russia's national identity merged with imperial claims in ways that were pernicious and consequential - the curse of empire.

By placing the war in Ukraine in the context of an era of Russian imperialism that spans three centuries, this book sheds new light on one of the bloodiest and most destructive conflicts of our time.

Martin Schulze Wessel is Professor of Eastern European History at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Introduction

Ever since 24 February 2022, Russia’s war against Ukraine has been a source of horror. After failing to quickly seize power in Kyiv, Russia’s invasion has been aimed at the physical destruction and symbolic annihilation of the neighboring country. Kremlin propaganda denies Ukraine its national identity, describes its political and cultural elites as “fascists,” and attempts to systematically dehumanize the political leadership around President Zelensky. Meanwhile, Russian troops are shelling civilians and civilian infrastructure. Entire cities lie in ruins. Far from the front line, the Russian army is bombing hospitals, kindergartens, and shopping centers. The violence sends a message: life is not safe in Ukraine, anywhere. A few months after the start of the invasion, a third of the Ukrainian population was on the run. This included 7 million within Ukraine and another 7 million – mainly women and children – who left the country. In the first months of the war, 1 million Ukrainians were funneled out of the occupied territories through so-called filtration camps. They were sent eastward and distributed across the Russian Federation, no doubt in the expectation that they would be assimilated into Russia. At the same time, but prior to mobilization, the Russian army sent above all members of non-Russian ethnic groups from far-flung regions to fight in a battle that involved heavy losses. This war of extermination therefore also involves an element of ethnic cleansing.

In Germany, it has taken a long time to open people’s eyes to the full extent of the atrocity and what this entails. One reason for this lies in the way German history is dealt with. The incomparably greater horror of the Holocaust and the German war of extermination in Eastern Europe had an inhibiting effect when it came to identifying Russian violence for what it is. It took some effort to realize that German history gave rise to a special responsibility for helping Ukraine.

History also plays a special role in the war itself. The legitimization that Russian President Vladimir Putin cites for the attack on Ukraine is historical in nature. Long before the invasion, he used historical narratives to justify Russia’s historical mission and deny Ukraine’s right to exist. This contrasts strikingly with Russia’s other military engagements. For the wars in Chechnya, Georgia, or Syria, the Kremlin did not invoke historical justifications, but sought to use international law to legitimate its claims. Justifying a war of aggression primarily through historical myths is also new in Putin’s Russia. Moscow’s claim to Crimea represents the best example of this. In fact, there is nothing “primordially Russian” about the peninsula: it is, in fact, a conquest that the Tsarist Empire made relatively late in its war against the Ottoman Empire. It only became part of the Russian Empire in 1783, which has not prevented Putin from claiming it as a legitimate possession. On the other hand, the fact that Crimea was transferred to Ukraine in Soviet times is, in Putin’s view, “unhistorical” – an error in the course of history that needs correcting.

Putin manipulates and instrumentalizes history. This statement is correct, but also quite banal. The Russian president is an amateur historian of the worst kind who thinks he understands history and can change it. As the British historian and security expert Mark Galeotti writes, Putin has “started a fight with history,” forgetting that history is a river that never flows backward.1 Ukraine is no longer the country that was part of the Tsarist Empire in the nineteenth century, no longer the Soviet republic of the 1960s and 1970s, no longer even the Ukraine of 2014.

The “special operation” that Putin has launched is Russia’s war. It is a war that cannot be understood solely in terms of the present, for it is not just about the rationally tangible interests of the clique that calls the shots in Russia. This is the flawed assumption at the heart of Western and especially German policy prior to 24 February 2022. In fact, the Russian decision to invade is based on myths and obsessions. The war rhetoric broadcast into the country day after day by state television caters to base instincts, implicitly or explicitly invoking history time and again. It is almost impossible to correct the flood of lies and half-truths. However, it is necessary to show that the set pieces of Russian propaganda themselves have a history. This consists of discourses with a long-term effect, which are conditioned by certain traditions of Russia’s imperial policy. Russia’s long-term structural problems thus emerge in the war against Ukraine.

However, the history of these problems does not encompass the entire Russian past. Since the start of the Russian invasion in February 2022, long-forgotten interpretations have resurfaced in the West that speak of a consistently violent tradition in Russian history and locate the roots of the current outbreak of violence as deeply as possible in that history. Comparisons are drawn between Putin and Ivan the Terrible, and the cruelty of the Russian Middle Ages is made responsible for Russia’s warfare today. In this way, Russian history is essentialized. But demonization and romanticization are just two sides of the same coin.

The Russian aggression against Ukraine cannot be explained simply through a present-day lens, using notions that the public in the West views as rational behavior. At the same time, however, this aggression is also not rooted in the infinite depth of Russian history. There is a medium-range historical depth to the explanatory framework that this book chooses: it involves the history of the modern Russian Empire, which began with the reign of Peter I. A structural problem arose at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the effects of which we are still dealing with today.

Russia, of course, was not the only country that exercised imperial rule. London, Paris, Madrid, Vienna, Berlin, Brussels, and other European metropolises were also imperial centers, if one understands an empire according to John M. MacKenzie’s well-founded definition. In his words, an empire is an “expansionist polity that seeks to establish various forms of sovereignty over people or peoples whose ethnicity is different from (or in some cases the same as) its own.” An empire thus becomes “a politically composite entity with, generally, a ruling center and a dominated periphery.” This can result in different forms of hegemony.2 Russia fits well into this general definition. The structural postimperial problems that emerge in Russia’s restoration attempt vis-à-vis Ukraine have, however, a different character than the West European decolonization processes, which were not without complications of their own. The Russian Empire also expanded into Europe by first incorporating the Ukrainian Hetmanate in the eighteenth century and then annexing the Baltic states and parts of Poland. In becoming a great power, Russia exposed itself to intense international competition in Europe and to a transfer of ideas that brought modern concepts, including the concept of nation, from the imperially dominated peripheries to the center of the empire. National issues arose on the western border of the Russian Empire – first the Polish question and then the Ukrainian question, as well as Baltic and Finnish aspirations for autonomy and independence. Each had geopolitical implications in the system of European states and acted as a model for other national movements in the Tsarist Empire and the Soviet Union. This is historically specific to the history of the Russian Empire, and, as early as the nineteenth century, it gave rise to an East–West clash of ideas in which Russia took on the role of an autocratic pole. Among the many empires of Europe, Russia did not stand out for the cruelty of its rule. What distinguished Russia from the other empires was the fact that a large land empire grew into Europe, so to speak, by annexing territories in Northeastern, East Central, and Southeastern Europe or by creating spheres of influence there.

France and Germany also established hegemonic orders in Europe during the Napoleonic era and under National Socialist rule, respectively, but these were comparatively short-lived. Russia, on the other hand, has exercised hegemony or a dominant influence in its western borderlands for more than 300 years. Western states have repeatedly attempted to contain Russia, and this has given rise in Europe to a liberal discourse critical of Russia since the nineteenth century. The clash with the West was thus inscribed in the traditional self-image of the Russian Empire over a long period of time. The contradiction between the dominant role Russia played in the eastern half of the continent in terms of power politics and the defensive position it found itself in against progressive thinking in Europe promoted exceptionalist ideas of Russia’s historical mission. Slavophile thinkers demanded that Russia should no longer allow itself to be measured by European standards. Even today, we are still burdened by this complex of imperial and nationalist ideas that were shaped in the nineteenth century. They are having a devastating effect on Ukraine in the current war. Moreover, they are preventing Russia from taking a place in a multilateral European and global order that is conducive to its own economic and social development.

We are also acquainted with such a development from Prussian-German...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.11.2025 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Neil Solomon |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| Schlagworte | autonomy and self-rule of Eastern European states • Catherine the Great • Colonisation • Eastern Europe • Empire • European alliances • foreign domination • Holodomor • how has Eastern Europe, and particularly the fates of Poland and Ukraine, been shaped by Russian imperialist ambition? • Imperial rule • Nationalism • Partition • Poland • Putin • Russia • Russia and Ukraine as unequal brothers • Russian-European conflict • Russian Exceptionalism • russian imperialism • Russian Sonderweg • separatism • Soviet Russia • Stalin • the Hetmanate and the Republic of Poland • Tsarist Empire • Ukraine • USSR • what are the roots of Russian imperialism in Eastern Europe? • where does Russian aggression against Ukraine stem from • why did Russia attack Ukraine? • Zelensky |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-6400-4 / 1509564004 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-6400-2 / 9781509564002 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich