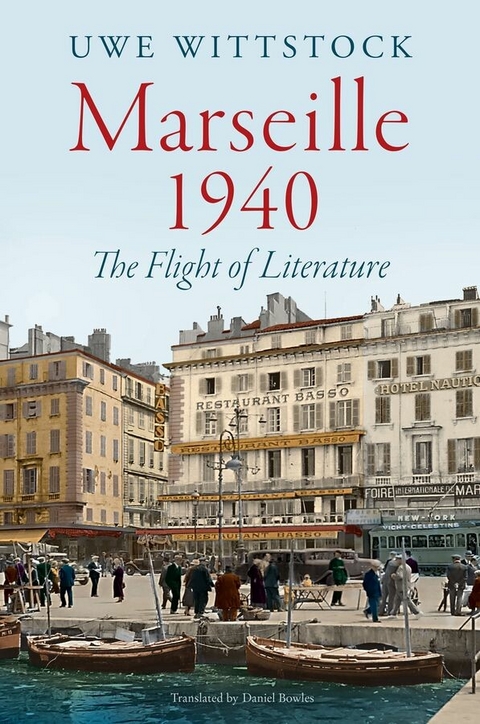

Marseille 1940 (eBook)

440 Seiten

Polity (Verlag)

978-1-5095-6543-6 (ISBN)

It is the most dramatic year in German literary history. In Nice, Heinrich Mann listens to the news on Radio London as air-raid sirens wail in the background. Anna Seghers flees Paris on foot with her children. Lion Feuchtwanger is trapped in a French internment camp as the SS units close in. They all end up in Marseille, which they see as a last gateway to freedom. This is where Walter Benjamin writes his final essay to Hannah Arendt before setting off to escape across the Pyrenees. This is where the paths of countless German and Austrian writers, intellectuals and artists cross. And this too is where Varian Fry and his comrades risk life and limb to smuggle those in danger out of the country. This intensely compelling book lays bare the unthinkable courage and utter despair, as well as the hope and human companionship, which surged in the liminal space of Marseille during the darkest days of the twentieth century.

Uwe Wittstock is a journalist, critic and author who lives in Germany. He was awarded the prestigious Theodor Wolff prize for journalism in 1989.

June 1940: France surrenders to Germany. The Gestapo is searching for Heinrich Mann and Franz Werfel, Hannah Arendt, Lion Feuchtwanger and many other writers and artists who had sought asylum in France since 1933. The young American journalist Varian Fry arrives in Marseille with the aim of rescuing as many as possible. This is the harrowing story of their flight from the Nazis under the most dangerous and threatening circumstances. It is the most dramatic year in German literary history. In Nice, Heinrich Mann listens to the news on Radio London as air-raid sirens wail in the background. Anna Seghers flees Paris on foot with her children. Lion Feuchtwanger is trapped in a French internment camp as the SS units close in. They all end up in Marseille, which they see as a last gateway to freedom. This is where Walter Benjamin writes his final essay to Hannah Arendt before setting off to escape across the Pyrenees. This is where the paths of countless German and Austrian writers, intellectuals and artists cross. And this too is where Varian Fry and his comrades risk life and limb to smuggle those in danger out of the country. This intensely compelling book lays bare the unthinkable courage and utter despair, as well as the hope and human companionship, which surged in the liminal space of Marseille during the darkest days of the twentieth century.

Backstories

Two Days in July 1935

Berlin, July 15 and 16, 1935

Hessler, on Kantstrasse, is a somewhat old-fashioned restaurant decorated in dark wallpaper, chandeliers, and ponderous stucco work. The entire rear wall of its dining room is occupied by a massive, dark brown sideboard, the tables before it standing at attention as precisely as if a Prussian sergeant had mustered them for roll call. From Kantstrasse it is only a few steps to the famous Romanisches Café just behind the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche. But it is quieter at Hessler and not nearly as packed.

Sitting alone at one of the tables, Varian Fry eats his supper. He is from New York, twenty-seven years old, a journalist. If there is such a thing as the epitome of a classical East Coast intellectual, he comes fairly close to it: slender, of medium height, clean-shaven, with a serious, alert expression and rimless glasses. Fry takes his time with his meal; he has nothing further planned for the day.

The streets are more full of life than they have been in previous weeks. The Berliners are enjoying the pleasant metropolitan evening; up until now, the summer has far too frequently been gray and rainy. Fry came to Germany two months ago aboard the Bremen, one of the fastest transatlantic ocean liners. Since then, aside from a few side trips to other German cities, he has been staying at the Hotel-Pension Stern on the Kurfürstendamm, a respectable, bourgeois establishment with rooms at reasonable rates, fifteen marks a day.

Fry is here on a research trip. Some people in New York think very highly of him. He is regarded as one of the promising newcomers among the city’s journalists. When he returns to America at the end of the month, he will assume the role of editor-in-chief at The Living Age, a sophisticated, soon-to-be hundred-year-old monthly devoted primarily to foreign affairs – a tall order for a man as young as him – and he has clear ideas about the issues he wants to highlight for his readers in the future. By his estimation, the greatest threat in international politics is posed by the fascist regimes in Europe, by Italy, Austria, and, above all, Germany. And so he has arranged with the publisher of The Living Age to first spend a few weeks in Berlin to form his own opinion of Hitler’s new Germany before joining the editorial team.

You need not be a prophet, Fry believes, to realize that Hitler’s political strategy will ultimately result in a war. It is sufficient to take his appalling proclamations seriously, verbatim, and not turn a blind eye to what he is doing to the people in his own country. Not many Americans have the courage to do so, however. All the large newspapers between New York and Los Angeles are reporting on the Nazis’ martial demonstrations, the military’s buildup of arms, the waves of arrests, the concentration camps, but with these stories, they scarcely prompt more than a shrug among their readers. Europe is far away, while the misery of the Great Depression in their own country, by contrast, can be felt acutely. Every attempt to gain control of the tenacious economic crisis occupies the Americans ten times more than news about a far-off despot in a weird brown uniform.

Over previous weeks, Fry has traveled across Germany, conducting dozens of interviews with politicians, economic leaders, and academics, but also with shop owners, with waiters, churchgoers, and taxi-drivers, the so-called simple people off the street. He is also learning German to gain a more direct entrée to the country. His notebooks are full to bursting. Once he is back in New York, he will be able to provide information about Hitler’s state not only in abstract numbers and concepts, but also from personal experience, descriptively and concretely, as is proper for a reporter. He has a great deal planned: transforming The Living Age into an alarm bell that will ring in the ears of even the deafest and most complacent of Americans.

After eating, Fry settles up and calmly makes his way back to Hotel Stern, just a short evening’s stroll away. The boulevards in western Berlin are the city’s promenades, flanked by elegant shops, cafés, cinemas, theaters. This is where well-to-do citizens live who do not want to withdraw into the tranquil villa districts, but to know something of the pulse of the metropolis. If, despite the Nazis’ narrow-mindedness, Berlin still radiates something akin to international sparkle, then it is here.

Fry enjoys the warm evening, a relaxed summer atmosphere seemingly blanketing everything, until while turning from Kantstrasse toward the Kurfürstendamm he suddenly hears shouting, yelling, splintering glass, screeching brakes. It sounds like an accident.

Fry dashes off – and runs right into a street fight on the Kurfürstendamm. Young men in white shirts and heavy boots are surging into the road from the sidewalks on both sides of the street. They are stopping cars, tearing open doors, yanking the occupants from their vehicles, and pummeling them. A windshield shatters – shouting everywhere, tussling, men lying on the ground being kicked, women collapsing from the blows and crying for help. Fry witnesses uniformed SA men outside a café sweeping the dishes from a patio table with a swipe of the arm, hoisting it up, and throwing it through the shop window into the establishment. One of the double-decker busses is stopped, and several thugs shove their way inside, dragging passengers off and beating them. Again and again the shouts: “Jew! A Jew!” or “Death to Jews!” Intimidated passersby quickly wrest their papers from their wallets to prove they are not Jews. In a panic, a man wearing a dark suit sprints into a cross street as several pursuers chase after him.

Fry stands amid the tumult in disbelief; no one pays him any attention. He sees a white-haired man with a gaping, hemorrhaging wound on the back of his head. Bystanders spit on him. He sees women pushed around by caterwauling attackers until they stumble and fall. He sees trembling, distraught faces streaming with tears. He sees policemen, dozens of policemen, but they do not rush to the aid of those attacked. Men call them “Jew flunkies” or “traitor to the Volk.” The officers regulate traffic, clearing free passage for busses, but nothing more.

Then Fry becomes aware of the droning chant in the background. A voice grunts a few words, which Fry cannot make out. A second line follows, then a third, then a fourth. Finally, the voice begins from the top, and the hooligans within earshot, in white shirts or SA uniforms, take up the words recited and roar them back rhythmically. It is like the antiphony in a church between cantor and chorus. Fry still cannot understand what is being shouted. Later he will find someone to transcribe it for him: “When the trooper’s off to join the fight / oh, he’s in a happy mood, / and if Jewish blood sprays from his knife, / then he feels twice as good.”

Fry flees into one of the cafés whose windows have not been shattered. From there he observes the street – its entire width now under the control of those bands of thugs, not one pedestrian dares set foot on the sidewalk or the road. Two SA men enter the café and patrol along the tables. A solitary, potentially Jewish diner stiffens, turning his head away in an attempt to avoid being spotted by the uniformed men. The two men bear down on him; one of them reaches for the dagger of honor on his belt and raises his arm, plunging the blade down into the diner’s defenseless resting hand, nailing it to the tabletop. The victim screams, shrieks, stares horrified at his hand, while the men laugh, the one ripping the knife back out again. They leave the café smirking. No one stops them.

At this point, the ruffians now gather on the street. A tall young man gives a brief speech, little more than a concatenation of buzzwords and insults, and then a kind of protest procession forms. The men chant “Jews, out! Jews, out! Jews, out!”, raise their arms in the Hitler salute, and march up the Kurfürstendamm.

Fry leaves the café – the situation seems to have settled down – and walks the few paces to Hotel Stern. Back in his room, he tries to think straight. He moves to the window, looking down onto the street. After several minutes, the demonstration procession returns on the opposite side of the street, followed by a single, slowly idling police car. The men still shout slogans. Fry does not understand them.

When the protest march has finally disappeared, Fry takes a seat at the desk in his room, grabs his notebook, compels himself to be calm, and begins writing down what he saw.

At first glance, Varian Mackey Fry comes across as a young man spoiled by good fortune: the son of a stockbroker, talented, exquisitely educated, successful, worldly. But this first glance deceives. A crack runs across his seemingly so very affable existence. Since his birth in 1907, his mother has suffered from severe depression; she has spent a great deal of time in clinics and was, perforce, unable to care for her son as she would have wanted. Her illness has left its mark on Fry. In spite of his outstanding abilities, he leads a precarious life. The feeling of having been cheated out of something to which he was entitled has made him irritable.

Those who get to know him more intimately occasionally...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 3.6.2025 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Daniel Bowles |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| Schlagworte | Aesthetics • Anti-Semitism • ART • authoritarian • Berlin • culture life • Dictatorship • Emergency Rescue Committee • exile • fall of France in 1940 • Franz Werfel • Genocide • Germany • Hannah Arendt • Heinrich Mann • Hitler • Holocaust • how did writers and artists live under the Nazis? • how writers and artists escape the Nazis? did persecution of writers and artists by the Nazis • Intelligentsia • Jewish • Joseph Roth • Lion Feuchtwanger • Literature • Marseille • Mary Jayne Gold • National Socialism • Nazi • Second World War • Thomas Mann • Totalitarianism • Varian Fry • Varian Mackey Fry • Walter Benjamin |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-6543-4 / 1509565434 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-6543-6 / 9781509565436 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich