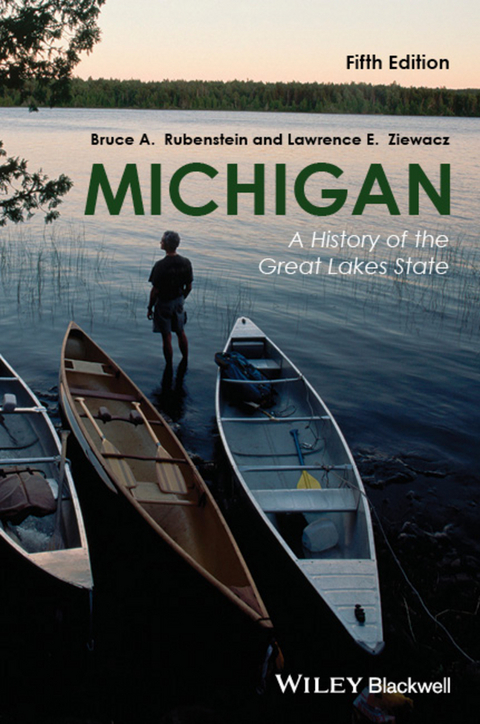

Michigan (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

9781118649732 (ISBN)

The fifth edition of Michigan: A History of the Great Lakes State presents an update of the best college-level survey of Michigan history, covering the pre-Columbian period to the present.

- Represents the best-selling survey history of Michigan

- Includes updates and enhancements reflecting the latest historic scholarship, along with the new chapter 'Reinventing Michigan'

- Expanded coverage includes the socio-economic impact of tribal casino gaming on Michigan's Native American population; environmental, agricultural, and educational issues; recent developments in the Jimmy Hoffa mystery, and collegiate and professional sports

- Delivered in an accessible narrative style that is entertaining as well as informative, with ample illustrations, photos, and maps

- Now available in digital formats as well as print

Bruce A. Rubenstein is Professor of History at the University of Michigan-Flint. A native of Port Huron, Michigan, he has co-authored two books with Lawrence Ziewacz: Three Bullets Sealed His Lips (1987) and Payoffs in the Cloakroom: The Greening of the Michigan Legislature, 1938-1945 (1995), both dealing with Michigan's political history. He also authored Chicago in the World Series, 1903-2005: Cubs and White Sox in Championship Play (2006) in addition to numerous articles on baseball and Indian-White relations in Michigan.

Lawrence E. Ziewacz, late Professor of American Thought and Language at Michigan State University, was a native of Sault Ste. Marie in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. He co-authored two books with Bruce Rubenstein: Three Bullets Sealed His Lips (1987) and Payoffs in the Cloakroom: The Greening of the Michigan Legislature, 1938-1945 (1995). He also co-authored The Games They Played: Sports in American History (1983) and was co-advisory editor of The Guide to United States Popular Culture (2001).The fifth edition of Michigan: A History of the Great Lakes State presents an update of the best college-level survey of Michigan history, covering the pre-Columbian period to the present. Represents the best-selling survey history of Michigan Includes updates and enhancements reflecting the latest historic scholarship, along with the new chapter Reinventing Michigan Expanded coverage includes the socio-economic impact of tribal casino gaming on Michigan s Native American population; environmental, agricultural, and educational issues; recent developments in the Jimmy Hoffa mystery, and collegiate and professional sports Delivered in an accessible narrative style that is entertaining as well as informative, with ample illustrations, photos, and maps Now available in digital formats as well as print

Bruce A. Rubenstein is Professor of History at the University of Michigan-Flint. A native of Port Huron, Michigan, he has co-authored two books with Lawrence Ziewacz: Three Bullets Sealed His Lips (1987) and Payoffs in the Cloakroom: The Greening of the Michigan Legislature, 1938-1945 (1995), both dealing with Michigan's political history. He also authored Chicago in the World Series, 1903-2005: Cubs and White Sox in Championship Play (2006) in addition to numerous articles on baseball and Indian-White relations in Michigan. Lawrence E. Ziewacz, late Professor of American Thought and Language at Michigan State University, was a native of Sault Ste. Marie in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. He co-authored two books with Bruce Rubenstein: Three Bullets Sealed His Lips (1987) and Payoffs in the Cloakroom: The Greening of the Michigan Legislature, 1938-1945 (1995). He also co-authored The Games They Played: Sports in American History (1983) and was co-advisory editor of The Guide to United States Popular Culture (2001).

Introduction vii

1 The Original Michiganians 1

2 The New Acadia 16

3 Under the Union Jack 42

4 Wilderness Politics and Economics 57

5 Challenges of Statehood 70

6 Decade of Turmoil 85

7 Defense of the Nation 102

8 Radicals and Reformers 115

9 Early Ethnic Contributions 130

10 Grain, Grangers, and Conservation 142

11 Development of Intellectual Maturity 157

12 Wood and Rails 176

13 The World of Wheels 195

14 From Bull Moose to Bull Market 210

15 Depression Life in an Industrial State 231

16 Inequality in the Arsenal of Democracy 249

17 Fears and Frustration in the Cold War Era 261

18 The Turbulent 1960s 274

19 Challenges of the 1970s 287

20 Toward the Twenty-First Century 299

21 Entering the New Millennium 317

22 Reinventing Michigan 334

Appendix A: Governors of the Territory and State of Michigan 344

Appendix B: Counties, Dates of Organization, and Origins of County Names 346

Appendix C: Michigan's State Song 351

Appendix D: Michigan's State Symbols 352

Index 353

1

The Original Michiganians

For generations, most schoolchildren have been told by well‐meaning teachers that their national heritage began in 1492 with Christopher Columbus’ discovery of America. Scandinavian scholars have objected to this interpretation, claiming that Leif Ericson arrived in North America before Columbus. In an effort to retain their national pride, Italian historians countered by promoting another of their countrymen, Amerigo Vespucci, as the true discoverer of America. European arguments over who discovered the North American continent are interesting, but they ignore a basic fact: non‐Europeans lived on the continent for at least 14,000 years before any European arrival. Thus, it is impossible for any European nation to claim “discovery.” Some scholars refute this argument by saying that Europeans can still boast discovery because they had never before seen North America. The foolishness of this contention was shown in 1975 when an Iroquois college professor from New York boarded a plane, flew to Rome, and upon arrival, announced that because his people had never been to Italy before he was claiming that land for the Iroquois Nation by right of discovery!

Ironically, Indians, so named by Columbus because he was certain that he had landed in India, lived in western Europe long before any Europeans established permanent colonies in North America. English fishermen, working the Newfoundland coast in the early 1500s, captured several natives and took them to England as examples of the “savage inhabitants” of the New World. After a few years, the amusement of viewing Indians diminished and another fishing expedition returned the captives to their homeland. Immediately these Indians spread tales of their adventures and told fascinated friends and relatives of the “world across the sea.” English culture and language clearly had intrigued the captives and they taught “white man's words” to their people. Therefore, when the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock in 1620 they were astounded when a descendant of one of those early visitors to England greeted them in English and assured them that others in his village spoke the language fluently. While it would be an exaggeration to say that Indians knew English “fluently,” it is fair to say that Europeans do not even have a valid claim to being the first English‐speaking residents of North America.

Throughout the years whites have been puzzled as to how Indians arrived on the continent and from whom they were descended. Several far‐fetched ideas have been put forth to answer these questions. An early popular theory was that Indians came by ferry from Europe. Disbelievers said that such a hypothesis was ridiculous and that the only logical answer was that Indians were descendants of people from the lost continents of Mu and Atlantis. In the 1600s, Puritans asserted that Indians were descendants of the “Lost Tribe of Israel,” who had wandered so long and far that they had been stripped of all godly qualities and had become savage “Children of the Devil.” This theory was accepted for over two centuries, although it, like the others mentioned, has absolutely no basis in fact.

By the late twentieth century, there were two accepted theories on how Indians arrived on the North American continent. Most anthropologists believe that small bands of Indians crossed the Bering Straits from Siberia approximately 14,000 years ago. Such a crossing was made possible because during the Ice Age sea levels declined and land bridges were formed linking Asia and North America. Since the continents are separated by a mere fifty‐six miles, it is assumed by many anthropologists that ancestors of the modern Eskimo were the first settlers of North America. Many Indians, however, accept a second theory. They believe that the Creator placed them on the continent, and that they have always been its inhabitants. Whichever theory is valid perhaps cannot be conclusively resolved. However, one point is indisputable: Indians were the original native North Americans.

The Three Fires

When Europeans first arrived on the North American continent, approximately 100,000 Indians, or 10 percent of the total Indian population north of Mexico, lived in the Great Lakes region. Of the several tribes residing in what is now Michigan, the most numerous and influential were the Ottawa, Chippewa, and Potawatomi. These tribes, which originally were united, split sometime before the sixteenth century, with the Ottawa remaining near Mackinac and in the lower peninsula, the Chippewa going west and north into Wisconsin and the upper peninsula, and the Potawatomi moving down the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. All continued to live harmoniously, without defined territorial boundaries, and never failed to recognize their common Algonquian language, dialect, and culture. They thought of themselves as a family, with the Chippewa the elder brother, the Ottawa the next older brother, and the Potawatomi the younger brother, and referred to their loose confederation as the “Three Fires.”

Figure 1.1 Indian tribes in the Great Lakes region from the time of European exploration to 1673.

The Chippewa, or Ojibwa, who inhabited the northern upper Great Lakes area, were the largest Algonquian tribe, estimated at between 25,000 and 35,000 at the time of European arrival in the New World. In order to survive in their harsh environment, the Chippewa lived in small bands, usually consisting of five to twenty‐five families, who could sustain themselves on the available food sources. During the summer, bands moved to good fishing sites and used hooks, spears, and nets to catch whitefish, perch, sturgeon, and other food fish. Men also hunted small game, while the elders, women, and children gathered nuts, berries, and honey. A portion of the gatherings and fish catch was dried and set aside for use in the winter. In the autumn, wild rice and corn were harvested, and hunts for large game, such as deer, moose, and caribou, were organized. As the “Hunger Moon” of winter set in, food grew scarce and families shared what little resources they possessed with their relatives. Sharing those items most valuable and scarce was an economic and physical necessity among band‐level people in order to survive. In the spring, maple sap was collected, boiled, and made into syrup and sugar for their own use and trade. While Chippewa in the lower peninsula engaged in limited farming, most of the tribe acquired agricultural staples through trade with the Ottawa and Wyandot.

Like all band‐level people, the Chippewa did not possess highly organized political structures. Leadership in their classless society was based on an individual's hunting or fishing skill, physical prowess, warring abilities, or eloquence in speech. Leaders had no delegated power but maintained influence through acts of kindness, wisdom, generosity, and humility. Positions of leadership always were earned and could not be passed from generation to generation as a hereditary right.

Chippewa social structure centered around approximately twenty “superfamilies” called clans. Each child belonged to his or her father's clan, and thus clans traced the line of an individual's descent. Furthermore, because marriage had to occur between different clans, a strong intratribal unity was fostered.

The second of the Three Fires, the Ottawa, was estimated to number nearly four thousand at the time of white arrival. Living in bark‐covered lodges in the northwestern two‐thirds of the lower peninsula, the Ottawa followed a subsistence pattern similar to that of the Chippewa, except that during the summer months they engaged in extensive farming. The Ottawa became known as great traders and their name, Adawe, means “to trade.”

Ottawa social and political structures were similar to those of the Chippewa, as was the Ottawa religion. The religion of the Ottawa and Chippewa was extremely sophisticated. Because Indians had always lived in nature, they thought of themselves as merely one of many elements constituting the environment. The white concept of man being a special creation apart from nature was foreign to every Indian belief of man's role in the universe. They believed that a Great Spirit, Kitchi Manitou, created the heavens and earth, and then summoned lesser spirits to control the winds and waters. The sun was the father of mankind, the earth its mother. Thunder, lightning, the four winds, and certain wildlife were endowed with godlike powers. In the Indians’ animistic belief structure any object, especially crooked trees and odd shaped rocks, could possess religious significance.

To Indians, religion was primarily an individual matter. At puberty each child journeyed to an isolated sacred place where a vision was sought through fasting. In most instances, a spirit would appear and grant the supplicant a personal spirit song and instructions for assembling a strong protective medicine bag. This spirit became the person's lifelong guardian, and it was a source of great comfort for the individual to know that a spirit was taking personal interest in his life.

Not all spirits were benevolent. Mischievous spirits, or “tricksters,” were ever present. These demigods were believed responsible for the annoyances of daily life, and all frightening sounds and accidents were caused by these playful, yet malevolent, sprites. Snakes and owls were thought to be earthly forms assumed by evil...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.11.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| Schlagworte | American Social & Cultural History • Detroit, Jimmy Hoffa, upper peninsula, UP, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan, Wolverines, Lake Erie, Lake Michigan, auto bailout, Henry Ford, state history, Auto Industry, Labor Unions, Native Americans, Fur Trade, College Sports • Geschichte • Geschichte der USA • History • Michigan /Geschichte • Regional American History • Regionalgeschichte Amerikas • Sozial- u. Kulturgeschichte Amerikas • us history |

| ISBN-13 | 9781118649732 / 9781118649732 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich