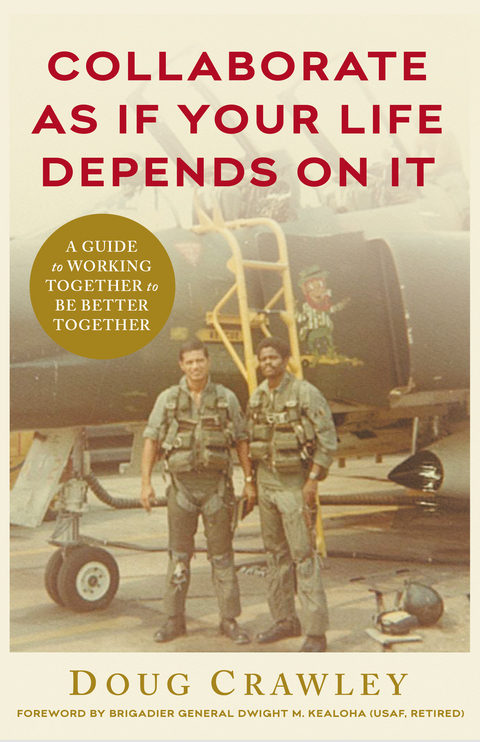

Collaborate as If Your Life Depends on It (eBook)

180 Seiten

Lioncrest Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-5445-0875-7 (ISBN)

When collaboration is absent-be it in business, sports, or relationships-success is likely to be absent, too. If you've been on a team where members favored a "e;me first"e; attitude or a "e;go-it-alone"e; approach, it was very likely a frustrating experience. In business, the issue is simple: we aren't trained on how to collaborate. If we are, it's limited to team-building exercises, and this doesn't create lasting change. Doug Crawley has learned how to collaborate in every area of his life: sports, business, ministry, and especially in the military, where his life literally depended on it!In this book, Doug shares stories from his life that illustrate the Five C's of collaboration: commitment, clarity, confidence, caution, and courage. You'll learn from his triumphs and his failures what it takes to begin working with others toward shared success. Collaborate as If Your Life Depends on It is your ticket to increased productivity, faster problem-solving, enhanced innovation, better customer experiences-and most important of all-vastly improved relationships in business and in life.

Introduction

“Russ, we’re in a spin,” I yelled from the back of our two-seat jet.

“Doug, we’re below 10,000 feet,” Russ, the front seat pilot yelled. “Get out. Eject! Eject! Eject!”

There was no further communication—and none was needed. In fact, I never even heard him say, “Eject.” As soon as I recognized that we were in a spin—and the plane was going down—I started my ejection sequence.

We both were able to eject, the parachutes attached to our seats shot out automatically, and we were left swinging under the canopies as the airplane burned on the ground.

A few seconds later, and we wouldn’t have gotten out.

I flew 185 missions during the Vietnam War, and if my pilot and I had not excelled at collaboration, I would not be alive to tell you my story.

I graduated from college in May of 1967. In July, I got a notice that I was to report to the Army on August 2nd. I knew I didn’t want to join the Army, though, so on August 1st, I flew to basic training in San Antonio, Texas, to become an airman in the U.S. Air Force—even though that was my very first time in an airplane. I was going into the military to fly airplanes, but I didn’t have a clue what it was all about.

Not long after I arrived, I was on the other side of the base when another soldier called my name and told me to leave the auditorium we were in and report back to my barracks. When I showed up, they said, “You’re going to Officer’s Training School.”

One day I was in basic training to be an airman; the next, I was in class as an officer trainee.

I went to officer training school and later to flight school, learned to be a navigator, and graduated seventh out of thirty-five people. Because of that ranking, I got to choose what kind of airplane I wanted to fly, so I picked a high-performance jet. If I had chosen to fly a cargo plane, I probably wouldn’t have gone to Vietnam—or, I would have just been going there, landing, and coming back. But the jet was glamorous. It was sleek, fast, and elite. Why would I drive a bus when I could choose a sports car instead? That jet was the epitome of flying!

I knew the basics of navigating a plane, but I had another stint at a more specialized flight school in Idaho to learn how to fly in the RF-4C high-performance jet and work with a pilot. I was assigned to be the navigator, with Major Ed Day as my pilot. We won the Top Crew award—just like in Top Gun, except we didn’t have any guns, so they called it Top Crew instead—for being the number one crew in our class, based on our training missions.

After a year of “Nav” school and six months of training in Idaho, we went through sea survival, where they dropped us in the water in a little dinghy with shark repellant, so we could learn how to survive at sea. Then, arctic survival, where we had to crawl a couple of miles through the snow, under tripwire, cold, wet, and freezing. Then they put us in mock prisoner-of-war camps where they harassed and intimidated us—but though we were put in some very strenuous situations, they were still Americans, so I knew that nobody was going to do me bodily harm. Lastly, I went through jungle survival training, spending the night in a jungle in the Philippines, learning how to survive and evade capture if I ever got shot down over enemy territory.

Ultimately, Ed and I were stationed at the Udorn Royal Thai Air Force base in Thailand. Because of a change in his assignment, Ed was no longer able to fly on a regular basis. As a result, I was crewed with Dwight M. Kealoha, or K, a pilot from Hawaii, whom I had met when stationed in Idaho.

Together, K and I flew reconnaissance missions over Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam—North and South.

Mission: Survival

We often flew at night, in total darkness. We were at war, so people were shooting at us. The airplane we flew, the RF-4C, has been described as “the last manned tactical reconnaissance aircraft in the U.S. Air Force inventory.” It was designed as a fighter aircraft with guns and bombs, but in our version those weapons were replaced with cameras so we could take photographs of military targets. Today, the military uses drones and satellites to take pictures of target sites, but back then that was our job—K flew the plane, and I sat in the back seat to navigate and operate the cameras. Flying reconnaissance has been described as the most dangerous job in the U.S. Air Force, and our mission’s motto was “alone, unarmed, and unafraid.”

All of the crews flying night missions received briefings before the flight, where they assigned us a set of targets. As the navigator, I’d spend the hours between the briefing and takeoff planning the course K and I would fly on our night mission. The GPS, which was called the inertial navigation system, or INS, was only good to within two miles. Remember, this is 1969. I couldn’t just put the coordinates in the computer and be led to the target. Using a paper map, I had to figure out which direction we wanted to go, based on the terrain—and determine points along that route that I would be able to identify on the radar. There were no lights on the ground, and if the stars weren’t out, it was dark.

The only light came when I dropped the photo flash carts over the target. They made a huge flash that lit up the whole sky—but I could only use three for a given target. Any more than that and the enemy would know where we were, and where we were going from the pattern of flashes, and they would shoot us down.

The low-level flying part of the mission—flying in, getting shot at while trying to acquire pictures of those targets, and getting back to the base—only lasted a couple of hours…but those hours were dangerous.

There were missions where they would call us in the air with new targets, at night. While airborne, we had to figure out the route and then go fly it. K would get us in a holding pattern, and I’d take out my map and plan the mission in the air, using a small flashlight and the light from the radar screen to figure out our position and where to go. He couldn’t see the map—or where we were going—so he was totally dependent on me.

We never saw other airplanes crash; people just wouldn’t come back from their missions. We didn’t know if they got shot down or not. We had no way of proving it, but we believed we lost as many or more people to running into the ground as to enemy fire. One mistake, on the part of either the pilot or the navigator, and we would crash.

When the enemy did start shooting at us, we could see the muzzle flashes. The tracers flew right by the cockpit. But we couldn’t move or duck or do anything. K had to keep flying, and I had to turn the cameras on and keep reading the radar scope, sharing it with him when he needed it. We’d be flying and K would say to me, “Doug, they’re shooting at us.” I’d look up and say some words I don’t use anymore then go back to what I was doing.

Most of the time, we couldn’t see anything, and often we flew down in what’s called karst, which is a rock formation that forms a valley we had to fly through. We were flying at 550 miles an hour 500 feet above the ground, so if K had turned at the wrong time, or if we got too close to the ground, we would have crashed—and died.

An article entitled “South Viet Nam: Eyes in the Sky,” in the July 29, 1966 issue of Time magazine, quoted then-Captain Gale Hearn, an RF-4C pilot in the RVN who specialized in night flying, as saying, “We’re more scared of those mountains than we are of the Viet Cong. You learn to trust your radar out there. When the moon goes down, it’s like flying through an ink bottle.”

The RF-4C was a tandem-seat jet, initially designed for two pilots, so there were controls in the back seat as well as in the front, allowing for either person to be able to fly the airplane. The dilemma in night flying, though, was that the radar system was designed such that we each had our own screen, but we could only utilize one mode at a time. I needed the Ground Mapping Mode (“GMM”) of the radar to navigate, keep us on course, and ensure that we acquired the assigned target. But that mode only helped with directional navigation—it didn’t say how high above the ground we were. K needed the Terrain Following Override (“TFO”) mode of the radar to ensure that we didn’t run into the ground, which we could not see. It didn’t give any information about navigating, though.

At any given time, we could either know whether we were on course to the target or how high we were above the ground—but not both.

If we missed our targets, someone else had to risk their lives to acquire the targets originally assigned to us. If we ran into the ground, we died and someone else would have to fly our mission. To make matters worse, when being shot at, we couldn’t move the aircraft to avoid being shot down, because we had to stay on our planned course to the target.

The only solution was to time-share the radar system. K needed to keep us from crashing and I had to keep us on course. We had to work together and collaborate as if each of our lives depended on it, which, in fact, they did.

There was no “I” or “me” in that...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.12.2020 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Wirtschaft ► Betriebswirtschaft / Management ► Unternehmensführung / Management |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5445-0875-1 / 1544508751 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5445-0875-7 / 9781544508757 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,9 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich