Packaging Design (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-35854-2 (ISBN)

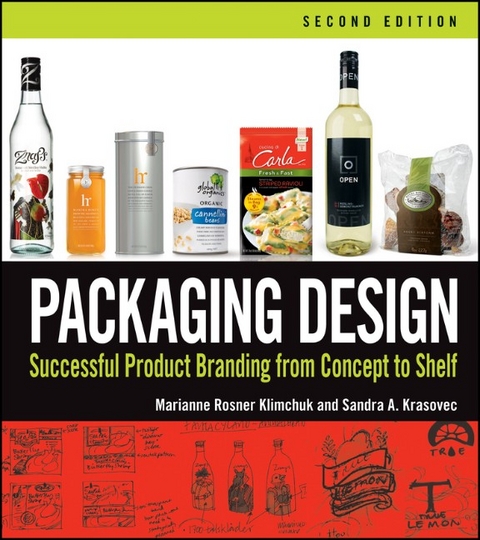

The fully updated single-source guide to creating successful packaging designs for consumer products

Now in full-color throughout, Packaging Design, Second Edition has been fully updated to secure its place as the most comprehensive resource of professional information for creating packaging designs that serve as the marketing vehicles for consumer products. Packed with practical guidance, step-by-step descriptions of the creative process, and all-important insights into the varying perspectives of the stakeholders, the design phases, and the production process, this book illuminates the business of packaging design like no other.

Whether you're a designer, brand manager, or packaging manufacturer, the highly visual coverage in Packaging Design will be useful to you, as well as everyone else involved in the process of marketing consumer products. To address the most current packaging design objectives, this new edition offers:

- Fully updated coverage (35 percent new or updated) of the entire packaging design process, including the business of packaging design, terminology, design principles, the creative process, and pre-production and production issues

- A new chapter that puts packaging design in the context of brand and business strategies

- A new chapter on social responsibility and sustainability

- All new case studies and examples that illustrate every phase of the packaging design process

- A history of packaging design covered in brief to provide a context and framework for today's business

- Useful appendices on portfolio preparation for the student and the professional, along with general legal and regulatory issues and professional practice guidelines

MARIANNE ROSNER KLIMCHUK is the Chairperson and Professor of Packaging Design at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in New York City and Partner at designPracticum, specialists in design leadership and management.

SANDRA A. KRASOVEC is Associate Professor of Packaging Design at FIT and Partner at designPracticum, specialists in design leadership and management.

The fully updated single-source guide to creating successful packaging designs for consumer products Now in full-color throughout, Packaging Design, Second Edition has been fully updated to secure its place as the most comprehensive resource of professional information for creating packaging designs that serve as the marketing vehicles for consumer products. Packed with practical guidance, step-by-step descriptions of the creative process, and all-important insights into the varying perspectives of the stakeholders, the design phases, and the production process, this book illuminates the business of packaging design like no other. Whether you're a designer, brand manager, or packaging manufacturer, the highly visual coverage in Packaging Design will be useful to you, as well as everyone else involved in the process of marketing consumer products. To address the most current packaging design objectives, this new edition offers: Fully updated coverage (35 percent new or updated) of the entire packaging design process, including the business of packaging design, terminology, design principles, the creative process, and pre-production and production issues A new chapter that puts packaging design in the context of brand and business strategies A new chapter on social responsibility and sustainability All new case studies and examples that illustrate every phase of the packaging design process A history of packaging design covered in brief to provide a context and framework for today's business Useful appendices on portfolio preparation for the student and the professional, along with general legal and regulatory issues and professional practice guidelines

MARIANNE ROSNER KLIMCHUK is the Chairperson and Professor of Packaging Design at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in New York City and Partner at designPracticum, specialists in design leadership and management. SANDRA A. KRASOVEC is Associate Professor of Packaging Design at FIT and Partner at designPracticum, specialists in design leadership and management.

Preface vii

Acknowledgments viii

1 The History 1

The Growth of Trade 3

Emerging Communication 4

Early Commercial Expansion 5

The Industrial Revolution 10

Mass Production 12

Mid-Century Expansion 21

Consumer Protections 29

The Packaging Design Firm 29

New Refinements in Packaging Design 32

Changing Times and Values 35

2 Defining Packaging Design 39

What is Packaging Design? 39

Culture and Values 41

Target Market 42

Packaging Design and Brand 43

Fundamental Principles of Two-Dimensional Design 55

Packaging Design Objectives 58

3 Elements of the Packaging Design 64

The Primary Display Panel 64

Typography 65

Color 83

Imagery 91

Structure, Materials, and Sustainability 104

Production 128

Legal and Regulatory Issues 143

4 The Design Process 148

Predesign 148

Beginning the Assignment 151

Phase 1: Observation, Immersion, and Discovery 153

Phase 2: Design Strategy 158

Phase 3: Design Development 175

Phase 4: Design Refinement 196

Phase 5: Design Finalization and Preproduction 198

Retail Reality 198

Key Points about the Design Process 200

5 The Packaging Design Profession 201

The Stakeholders 201

Managing the Business 213

Entering the Profession 217

Glossary 223

APPENDIX A Consumer Product Categories 230

APPENDIX B Materials And Tools 232

Bibliography 233

Professional Credits 235

Figure Credits 237

Index 239

Chapter 1

The History

Humans have needed to gather, collect, store, transport, and preserve goods since time immemorial. Following is a brief exploration of how the advancements of civilizations, the growth of trade between peoples, technological inventions, and countless other historical events facilitated the evolution of what we have come to call packaging design.

From as early as the Stone Age, containers were fashioned from woven grasses and fibers, bark, leaves, shells, clay pottery, and crude glassware. These materials were used for holding goods—food, drink, clothing, and tools—for everyday use (fig. 1.1). Archaeologists’ discovery of such objects shows that early economies depended on packaging for sharing and transporting goods. As various peoples transitioned from nomadic hunting and gathering to settled agricultural production, demand was created for goods that were only produced in specific places. Trade in such goods was the forerunner to modern market economies (fig. 1.2).

The Sumerians, among the earliest of settled societies, dating back over five thousand years, developed a written communication system, initially consisting of a system of pictographs that enabled new forms of visual identification. With the Sumerian practice of year-round agriculture came a surplus of storable food, and pictographs served to identify these stored products (fig. 1.3). The Phoenician civilization inherited Sumerian writing and further developed it, creating the single-sound symbols—an alphabet—that became the foundation for the further evolution of Western written languages. Thus Sumerian pictographs evolved into the syllabic symbols that became the basis for the forms of written communication used by many cultures for almost two thousand years.

These early symbol systems developed from the need to establish identity in three ways: personal (who is it?), ownership (who possesses it?), and origin (who made it?). Such symbols were the forerunners of trademarks and brand identities. The Greeks took the letters of the Phoenician alphabet and turned them into beautiful art forms, standardizing each with component vertical and horizontal strokes based on geometric constructions. This marked the beginning of letterform design (fig. 1.4).

Scrolls made from papyrus (a wetland plant) and dried reeds and parchment made from specially prepared animal pelts were among the first portable writing surfaces. The Chinese emperor Ho-di of the Han dynasty produced papers in approximately 105 BCE. Researchers have discovered that the Western Han dynasty used these materials not only for writing but also for wallpaper, toilet paper, napkins—and wrapping used for packaging. Chinese papermaking techniques advanced over the next fifteen hundred years, reaching the Middle East and then spreading across Europe.

Fig. 1.1

Neolithic jar.

Fig. 1.2

Pictographics, naos of the temple at Ed Dakka, Egypt.

Close examination of the image of an interior temple wall reveals the visual identification of goods by pictorial representation.

Fig. 1.3

Symbol for wheat.

The Sumerian symbol for wheat is one of the earliest examples of an icon used for visual communication.

Fig. 1.4

Early letterforms.

The Growth of Trade

As people made their way around the world, goods were transported greater distances and so there was a need for vessels to carry these goods. Certain commodities are particularly identified with trade across great distances: perfumes, spices, wine, precious metals and textiles, and, later, coffee and tea. Merchants, missionaries, nomads, and soldiers traded such goods along early intercontinental trade routes linking Europe and Asia, the Silk Road being the most notable. Crusaders traded along routes between Europe and the Middle East. Such activity created the need for a wide variety of packaging to contain, protect, identify, and distinguish products along the way.

Hollow gourds and animal bladders were the precursors of glass bottles, and animal skins and leaves were the forerunners of paper bags and plastic wrap. Skilled artisans handcrafted ceramic bottles, jars, urns, containers, and other decorative receptacles to house incense, perfume, and ointments, as well as beer and wine (fig. 1.5).

In the twelfth and thirteen centuries, an identifiable merchant class, concerned with moving products from one locale to another, began to appear. Buying and selling goods, as opposed to farming or crafting material necessities, thus became a way to make a living.

Along with the merchant classes came an interest in the wider world and increased demand for goods from faraway places.

Fig. 1.5

Paper wrappers.

Paper wrappers are among the forerunners of modern packaging design. Here the actor Iwai Hanshiro VI holds a dish of rice cakes as a memorial offering, while a child at his feet holds a broadside of a paper game board.

Emerging Communication

Handwritten script on paper or parchment gave way to printing. The Chinese are credited with inventing the wooden printing press and then movable clay type. Tinplate iron, developed in Bohemia (a region in central Europe), allowed printing to take hold throughout Europe.

Around 1450, Johannes Gutenberg assembled his printing press. Utilizing movable and replaceable wooden or metal letters, it brought together the technologies of paper, oil-based ink, and the winepress to print books (fig. 1.6). The use of movable type lowered the cost of printing and, in turn, the price of printed materials. The general public’s access to printing led to a rapid increase in the demand for paper and sparked a revolution in mass communication.

Innovations in book design emerged during the Renaissance (from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries) in the areas of typography, illustration, ornament, and page layout, as well as through new kinds of paper and printing materials. Visual communication was thus greatly advanced.

In the mid-1500s Andreas Bernhart, a German paper-mill owner, was among the first tradesmen to print his name (with a decorative design) on paper wrappers to package his products. Bernhart’s wrappers pointed the way to merchandising with printed designs.

Billboards and broadsides—announcements of laws and government decrees posted on the sides of buildings—were the first forms of advertising. Advertising quickly became a vehicle for selling “consumer” products and frequently depicted the product’s packaging design. In fact, in early British newspapers, dating from the early 1800s, vendors posted, or advertised, products such as jars of tea, medicine bottles, and tobacco with illustrations of their printed labels.

Packaging design evolved with the marketing opportunities that the visual experience provided, and packaging became critical to sales. Design disciplines grew out of the need to communicate information in graphic form, melding with the material wants and needs of everyday life. In essence, the combination of the physical container, or packaging, and the written communication about the goods it contained became the foundation for packaging design today.

Fig. 1.6

Johannes Gutenberg examining his first press proof.

Early Commercial Expansion

Eighteenth-century Europe saw great commercial expansion, accompanied by the rapid growth of cities and a broader distribution of wealth that included the working class. Technological advancements allowed production cycles to keep up with the increased population. Mass production provided at low-cost, readily available goods, which in turn led to the concept known today as mass marketing.

In the 1740s, America, a British colony with a relatively small population, imported most manufactured luxury goods from England, France, Holland, and Germany. In 1750, there were only one million inhabitants of European origin in America, but by 1810 this number had ballooned to six million. Still, there was little to induce most traders to print their names and addresses on their goods, since most of the population of both America and Europe were illiterate. In Britain, for example, of its nine million inhabitants, only eighty thousand could read. However, packaging designs were created to attract these educated, wealthy, upper-class consumers.

Out of concern for hygiene among the growing bourgeoisie emerged two new features in the home: the toilet and the bathroom. As product development increased to meet consumer demand, packaging designs for products such as toiletries, bottled beers, antidotes, pots of snuff, canned and bottled fruits, mustards, pins, tobacco, tea, and powders functioned to identify their manufacturer and communicate the products’ purpose (figs. 1.7, 1.8, and 1.9).

With the goal of attracting affluent consumers, coats of arms, crests, and shields were commonly used as graphic elements on packaging designs during this period. These symbols, ornately detailed, signified the family that manufactured the goods or provided a regional mark of distinction. Labels also often depicted images of powerful animals such as lions, unicorns, and dragons. Traditionally, such emblems adorned shields and armor as a means of distinguishing warriors on the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.2.2013 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Design / Innenarchitektur / Mode |

| Technik ► Architektur | |

| Wirtschaft ► Betriebswirtschaft / Management ► Marketing / Vertrieb | |

| Schlagworte | Advertising • Business & Management • Grafikdesign • Graphic Design • Marketing & Sales • Marketing u. Vertrieb • packaging design, product branding, exploring package design, what is packaging design?, package design workbook, marianne klimchuk, groth, calver, dupuis • Verpackung • Werbung • Wirtschaft u. Management |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-35854-6 / 1118358546 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-35854-2 / 9781118358542 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich