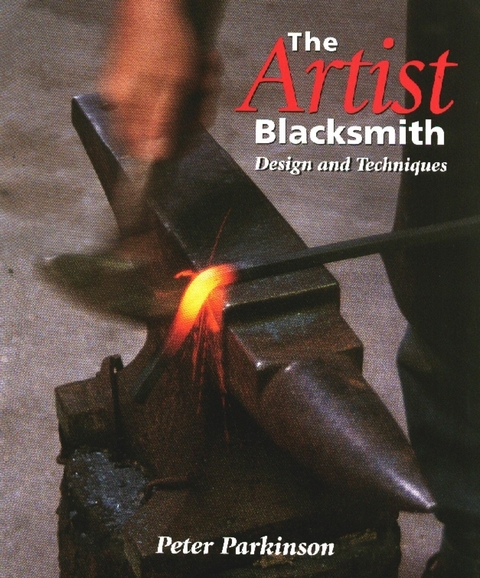

The Artist Blacksmith (eBook)

160 Seiten

Crowood (Verlag)

978-1-84797-783-0 (ISBN)

Peter Parkinson has spent a lifetime working as a designer and maker. He studied Industrial Design at the Royal College of Art. In 1979 he discovered blacksmithing and set up his first workshop. From here he initiated a BA course in Metals and taught a new generation of young blacksmiths before leaving his teaching to become a full-time artist blacksmith.

The Artist Blacksmith is the essential handbook for anyone interested in bringing a creative, contemporary approach to this ancient craft, and for those already hooked who want to improve and expand their skills.

Peter Parkinson is an artist blacksmith, making pieces of contemporary metalwork and public art. His work can be seen in public buildings and spaces in many cities in Britain. He also teaches short courses on blacksmithing and has written two other books for Crowood: The Artist Blacksmith and Forged Architectural Metalwork.

1 WORKSHOP AND EQUIPMENT

THE WORKSPACE

Setting up your own workshop is a crucial step and there are a number of important points to be taken into account when considering the use of a particular building or space. The essential requirements are size, accessibility and an electric power supply.

To begin blacksmithing the nature of the space is more important than the size. My first workshop was only 2.4m (8ft) long by 2m (6ft 3in) wide, but it did have the virtue of a concrete floor and a high ceiling. If there is room for a forge and anvil, and enough space to move comfortably around the anvil, you have a potential forging workshop; minimal but viable. This said, a bigger space is clearly desirable, allowing more equipment to be fitted and space to lay out and construct larger projects. But if a small space is all you have, do not be discouraged.

A concrete floor is very desirable but not as essential as a ceiling high enough to allow you to swing a hammer at full stretch – 2.4m (8ft) is a minimum. Do not forget that light fittings are usually lower than the ceiling itself. It is remarkably easy to remove lights with a careless swing of a hammer, even when you thought you knew where they were. Ceiling lights should be placed high up and out of reach. A large workspace is no good if the roof is too low.

Access is a major consideration. Moving equipment, metal, fuel and so on into the building requires a reasonably easy access. Steps, for example, are a real problem. A level access and a wide door – preferably double doors – are a great advantage. It is so easy to put together a large piece of work, and forget that it has to be taken out of the workshop when it is finished.

Fire risk must also be evaluated. The most suitable type of building is of conventional brick, concrete or stone construction with slate or tile roofing, or utilitarian steel framing and metal cladding. Whilst this does not preclude the use of a wooden shed, it does mean that more care must be exercised than in, say, a brick building. This may mean lining a special part of the workshop with non-inflammable sheeting for welding or grinding. A wooden shed also needs a hard, preferably concrete, floor.

The author’s first workshop. Just enough room for a coke forge, anvil and vices fitted to a bench.

It must be acknowledged that noise is a potential problem. In my experience, not quite so much the noise of hammering at an anvil, but the whining noise of ancillary equipment such as a fan or angle grinder. Clearly if your intended forging shop is adjacent to the house next door, you may have a problem. Distance can make a difference and a screen of shrubs and trees may help. Working only at particular times of the day – never after 6pm, for example – might also help endear you to your neighbours.

ELECTRIC POWER AND LIGHTING

Electric power is essential. Even if you wish to blow your forge with traditional bellows, you will still need to have electric light to see what you are doing. If your workshop is situated where you live, a catenary wire run from the house carrying the power cable is not difficult to arrange. The power should come through its own fuse in your domestic consumer unit. Fit a fuse rather than a miniature circuit breaker, if you are going to use an arc welder. This will tend to trip the circuit breaker, while a wire fuse is more tolerant.

It is better to fit more power sockets than you think you need, and preferably use double ones to reduce the hazard of long trailing leads to a hand electric drill or angle grinder. With so much metal in the workshop, good earthing is essential. RCD (Residual Current Device) sockets are also a worthwhile safety device, giving you protection should you cut a trailing cable with a power tool or a piece of hot metal.

A fence design laid out on the concrete workshop floor.

Traditionally a blacksmith’s workshop was an ill-lit place, with few windows, since the smith needed to ‘see the colour of the metal’. That is, to judge its temperature. It is very important to be able to see how hot the metal is, but this does not mean that the workshop has to be gloomy. A normally lit interior space allows you to judge the colour of the metal perfectly well, and crucially enables you to see what you are doing. A light-coloured floor and walls provide a good background against which you can judge a bar for straightness. If the floor and walls are a dark colour, it may be necessary to use a piece of white painted board propped up, to act as a background.

Direct sunlight can be a problem. For this reason, windows may be better fitted with obscured glass and ideally should be in a north-facing wall. Sunlight coming directly through a window and shining on the metal, can make judging the heat very difficult. If there is really no alternative – or if you want to work out of doors for instance – the hot end of the metal can be offered into a steel drum, or under the shade of the forge hood, where its colour can be seen.

For preference, windows should be set fairly high. If they are at bench height or lower, they can be easily broken by the careless handling of a length of metal or a dropped tool. A window above a bench is a good arrangement from the point of view of illumination, but beware of grinding sparks impacting the glass. The metal particles stick and gradually turn the window brown with rust.

A good flat, solid floor is important, not least because blacksmithing equipment is heavy and subject to impact. A smooth concrete floor is fireproof, enables equipment to be moved easily and allows chalk lines to be set out as a guide for a particular piece of work. If the floor is truly level as well as flat, a spirit level can be used to check pieces of work and a plumb line hung from the roof will be at right angles to the floor surface. This can be very useful for ensuring that an upright feature – the stem of a floor standing lamp, for instance – is set truly vertical in relation to its base.

The workshop should be well ventilated, but not draughty. There is a risk of fumes from the forge fire and from arc welding operations. A coal or coke fire is dusty, and grinding produces dust. For these reasons, many smiths prefer to work with the door open to provide a flow of fresh air. But a direct draught near the fire should be avoided since it can blow fumes from the burning fuel into the workshop before they can escape up the flue.

BASIC EQUIPMENT AND LAYOUT

Essential equipment is the forge, anvil, a heavy vice and a bench. A great deal can be achieved with just these and a few hand tools. It is an advantage to add a hand electric angle grinder, an electric arc welder, and a number of other tools that will be reviewed in Chapter 15. But whatever else you may have, or aspire to, the forge and anvil are the heart of the workshop.

The forge is simply a heat source and may be coal, coke, gas or oil-fired. There are many different types and sizes, each with its own advantages and disadvantages (see below). Like motor cars, they all ultimately get you there, but with varying degrees of efficiency, comfort, speed and cost.

Since it needs a flue, a coal or coke forge tends to fix the layout of the workshop. Its position needs careful thought. A gas-fired forge running on propane, or an oil-fired forge burning paraffin needs no flue in a well-ventilated workshop, since the fuel burns cleanly without noxious fumes. It should be remembered, however, that any kind of hydrocarbon fuel produces carbon dioxide, and with a restricted air supply can also produce carbon monoxide. So good ventilation is important. These forges provide a heated chamber – similar to a potters kiln – accessed though doors at front and back. Since they are relatively light in construction, and do not need a fixed flue, they can be placed on a base fitted with castors, and moved as necessary. This permits a more flexible layout to the workshop, enabling the forge to be sited to suit the particular job.

Solid fuel forges often have a water trough attached to the front of the hearth. It is essential to have some form of tank or trough in which to cool or quench the metal. An old oil drum may serve, although there is some advantage in having a long tank, since a hot bar may be laid across it and areas quenched at either side of a heat, without flooding too much water on the floor.

WHICH FORGE?

COAL OR COKE FORGES

Advantages

◆ Give a short heat on a bar.

◆ Good for providing a local heat in the middle of a bar, to make a tight bend for example.

◆ Very suitable for fire-welding operations.

◆ Flexible access to the heat source – a large or awkward piece may be reheated.

◆ Since a fan controls the fire, it may be shut down between heats, conserving fuel.

◆ If the fan is silenced, it can be very quiet to use.

Disadvantages

◆ More difficult to install. Must have a flule to vent fumes.

◆ Dirty. Even with a good flue it produces dust in the work-shop.

◆ Difficult to achieve a heat much longer than, perhaps, 6in (15cm).

◆ Metal left unattended in the fire will almost certainly burn.

◆ Physically a larger unit than a gas or oil forge.

WHICH FORGE?

COAL OR OIL FORGES

Advantages

◆ Easy to install – no flue.

◆ Can be made mobile by placing on a trolly...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 30.4.2014 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 186 colour phtoographs 123 black & white illustrations |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Heimwerken / Do it yourself | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Kreatives Gestalten | |

| Weitere Fachgebiete ► Handwerk | |

| Schlagworte | Anvil • baba • Bending • Drawing Down • Forge • Foundry • hot cutting • iron • metalsmithing • Punching • twisting and joining • upsetting and spreading |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84797-783-9 / 1847977839 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84797-783-0 / 9781847977830 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich