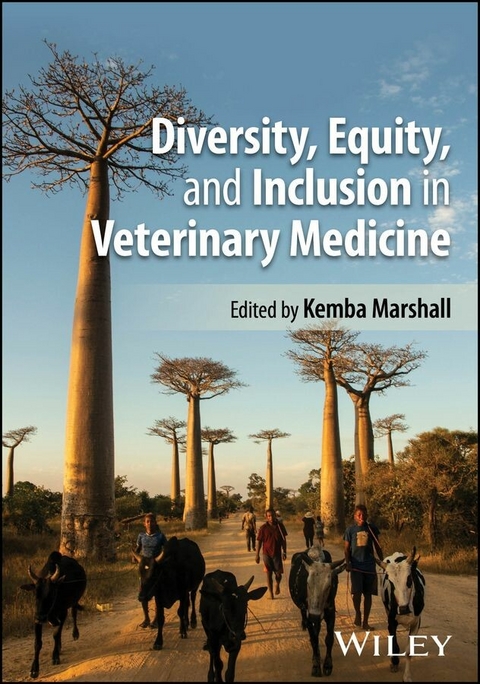

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Veterinary Medicine (eBook)

700 Seiten

Wiley (Verlag)

978-1-394-21710-6 (ISBN)

An insightful discussion of DEI and its application to a wide variety of real-world veterinary settings

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Veterinary Medicine takes a broad approach to the concept of DEI, delivering a practical discussion of effective strategies for applying diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) practices within the veterinary setting. Written by a diverse set of voices, the book provides a comprehensive understanding of DEI as it relates to veterinary medicine. Arranged from A to Z, the 26 chapters discuss important concepts in DEI, with actionable advice for how to incorporate DEI into the practice of veterinary medicine.

The chapters define the concepts, explain why each concept is important to veterinary medicine, and give practical examples of how to apply the concepts in the real world. Each chapter stands on its own and can be approached individually but taken together these chapters expand the boundaries of DEI into topics that are both familiar and novel.

Readers will also find:

- A thorough introduction to the concept of access to care and one health medicine through the lens of DEI

- Comprehensive explorations of equity, intersectionality, justice, representation, and other central DEI concepts that impact the veterinary profession's ability to benefit society

- Practical discussions of how unconscious bias and cultural competency impact both client and team interactions impacting patient care

- In-depth examinations of specific community engagement, including First Nation, queer, and neurodiverse communities

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Veterinary Medicine is an invaluable resource for practicing veterinarians, veterinary technicians, veterinary practice managers, other veterinary professionals, veterinary students, veterinary technician students, and anyone involved with animal health.

The editor

Kemba Marshall, MPH, DVM, DABVP (Avian Medicine), SHRM-CP, is the CEO of KLMDVM Consulting LLC and is based in St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

An insightful discussion of DEI and its application to a wide variety of real-world veterinary settings Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Veterinary Medicine takes a broad approach to the concept of DEI, delivering a practical discussion of effective strategies for applying diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) practices within the veterinary setting. Written by a diverse set of voices, the book provides a comprehensive understanding of DEI as it relates to veterinary medicine. Arranged from A to Z, the 26 chapters discuss important concepts in DEI, with actionable advice for how to incorporate DEI into the practice of veterinary medicine. The chapters define the concepts, explain why each concept is important to veterinary medicine, and give practical examples of how to apply the concepts in the real world. Each chapter stands on its own and can be approached individually but taken together these chapters expand the boundaries of DEI into topics that are both familiar and novel. Readers will also find: A thorough introduction to the concept of access to care and one health medicine through the lens of DEI Comprehensive explorations of equity, intersectionality, justice, representation, and other central DEI concepts that impact the veterinary profession s ability to benefit society Practical discussions of how unconscious bias and cultural competency impact both client and team interactions impacting patient care In-depth examinations of specific community engagement, including First Nation, queer, and neurodiverse communities Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Veterinary Medicine is an invaluable resource for practicing veterinarians, veterinary technicians, veterinary practice managers, other veterinary professionals, veterinary students, veterinary technician students, and anyone involved with animal health.

Preface

At the age of 8, I announced to my parents that I was going to become a veterinarian. Together, my parents and siblings could never have imagined the path that veterinary medicine would set our family on. We have owned countless German Shepherds and African cichlids. We have driven cross country with snakes in pillowcases and feeder mice in habitats. We have taken African safaris, air‐boated along alligator farms, and visited zoos domestically and internationally, all in pursuit of experiencing veterinary medicine.

As a child, I had the great fortune of seeing a lot of different professions. I saw pediatricians, obstetricians, gynecologists, dentists, postal carriers, pharmacists, home builders, HVAC specialists, restaurateurs, attorneys, and teachers. However, when I saw Dr. Larry Wallace vaccinating my family's German Shepherds, I saw my future. I could have never imagined my future would hold the pages you are now reading.

In order to tell you how this book came about, let us go back and see how veterinary medicine started in the United States and where we are as a profession right now.

Lyon, France, is the official birthplace of veterinary medicine, opening the first veterinary school in 1761. In the United States in 1776, George Washington issued an order that each newly formed regiment in the Revolutionary War include a farrier knowledgeable in horse care to look after the cavalry horses. Farriers were not credentialed veterinary caregivers but provided necessary animal care for these working horses. This was the foundation of the eventual creation of the US Army Veterinary Corps.

During the Civil War, the Union Army recognized the need for a formal veterinary service. The Confederate Army conversely relied on each soldier to care for their own horse during the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln established the US Department of Agriculture on May 15, 1862, under the Department of Agriculture Act (Michigan State University CVM 2019).

Lincoln also signed into law the Morrill Act, which established the first group of Land Grant Institutions, in 1862 (NIFA). The Morrill Act set in motion a set of policies designed to harness the power of education to positively impact agriculture and rural America. Lincoln remarked that “…no other human occupation opens so wide a field for the profitable and agreeable combination of labor with cultivated thought, as agriculture.” The first Morrill Land Grant College Act granted 30,000 acres of land for each senator and representative. The first Morrill Act led to the construction of agricultural and mechanical schools (known also as land grant institutions, or LGIs). Significant portions of the goal of the Morrill Act were stymied when Confederate land grant institutions refused to integrate. Thus, the second Morrill Act was signed 28 years later in 1890, which granted money instead of land to Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) as LGIs to begin to receive federal funds to support teaching, research, and extension intended to serve underserved communities of African Americans and other minorities who were prevented from attending many of the 1862 LGIs (Lawrence 2022; McMillan 2012). Without the granting of land, the 1890 institutions faced significant hurdles in building teaching institutions on par with the 1862 institutions.

Later, veterinarians made a significant professional contribution to the 1906 Federal Meat Inspection Act, which was signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt. This law requires pre‐ and postmortem inspection of livestock and authorizes the US Department of Agriculture to monitor and inspect slaughter and processing operations. Sanitary standards for slaughterhouses and meat‐processing plants were also established in 1906. In 1916, as the United States was preparing to enter World War I, President Woodrow Wilson and Congress passed the National Defense Act of 1916, including the creation of the Veterinary Corps of the US Army.

As the number of horses in use for transportation and farming began to decline, two British government reports in 1938 and 1944 suggested that veterinarians should specialize in the treatment of farm animals. In 1958, veterinarians would again contribute to significant legislation, the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act. This Act ensures that animals are sedated and completely insensible to pain just prior to slaughter. Inspectors of the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service at slaughtering plants ensure that these guidelines are met. There are approximately 1200 veterinarians employed in public practice at the USDA. Veterinarians are heavily involved in ensuring that meat, egg, and poultry producers comply with sanitation standards.

Small animal practice as a business may be attributable to one woman, Marla Dickin and her companion animal charity, the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals of the Poor (PDSA), created in the United Kingdom (UK) in 1917. Four sentences encapsulated the PDSA value proposition: “Bring your sick animals: Do not let them suffer! All animals treated. All treatments free.” The people who worked at PDSA clinics had no veterinary training. The people who took their animals to PDSA would not have been able to afford a professionally trained veterinarian. Nevertheless, the veterinary community frowned upon the PDSA. G.H. Livesey, a prominent veterinarian of the time, referred to people involved in animal welfare as “cranks” and said, “All of us who have had experience in dog practice know that there are ladies (generally childless) who have to turn their attention to something, and nearly always they turn to dogs.” By 1927, PDSA treated 410,000 animals annually. These patient numbers indicated the possibility for dog and cat medicine to be enough to support a business.

In 1926, when Sarah Martha Grove Hardy left PDSA £50,000, the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons tried to claim some of the funds. This claim was rejected, and with that infusion of cash the PDSA flourished. As time went on, veterinarians did go on to provide professional services for PDSA. As a matter of fact, PDSA is still in existence today, serving 2.3 million animals annually in the United Kingdom (Todd 2017). In the United States, Daniel Salmon was the first veterinarian to earn a doctorate in 1876 and went on to lead the Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Animal Industry. One of Dr. Salmon's first accomplishments was to eradicate bovine pleuropneumonia (National Agricultural Library n.d.).

In the US, 1903 saw the first female veterinarian enter the profession, graduating from McKillip Veterinary College in Chicago. In 1910, Elinor McGrath graduated from the Chicago Veterinary College and Florence Kimball graduated from Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. Both of these women would go on to become small animal veterinarians (Wuest 2019).

Through the types of practice, public vs. private, and the animal types we focus on (exotic, avian, small, mixed, large, food animal or zoo), no two days for no two veterinarians look exactly alike. We excel in the diversities of our practice type, location, and lived experience of veterinary caregivers. Ethnic, cultural, and racial diversity, on the other hand, have long been a challenge for our profession.

In late 2019 and early 2020, as we were in the midst of the global COVID‐19 pandemic and social unrest, I was forced into increased interest in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) within veterinary medicine. As images of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery were seen internationally, many of my White veterinary colleagues began calling me to talk. I was so personally traumatized by the events that I initially refused to take any of those calls. I thought I had nothing to say. It turns out I was wrong about that; I had a lot to say. I realized that I had influence in the veterinary space and a responsibility to leverage that influence. I penned a letter to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) questioning an online pledge to reaffirm the AVMA's commitment to DEI. As a member in good standing with decades of membership dues paid, I was unaware that the AVMA had such a written statement of DEI support. I also saw no commitment in action on the AVMA's part to advancing DEI. That letter, along with the AVMA's response to my letter, led to me joining the AAVMC/AVMA Joint Commission for a Diverse, Equitable and Inclusive Veterinary Profession in 2020. The Commission's Strategic Recommendations were released on October 28, 2021 (AVMA 2022).

I began to develop the concept for this book during my time on the Commission. Many books and articles have been written about DEI in veterinary medicine (e.g. Kornegay 2011). Dr. Lisa Greenhill has had significant contributions in this area and continues to provide evidenced‐based thought leadership in her role as Chief Diversity Officer at the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges (AAVMC) (Greenhill et al. 2013). At the Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine, Dean Willie Reed (San Miguel et al. 2014) championed DEI in veterinary medicine for years and worked closely with Dr. Latonia Craig, who is now Chief Diversity Officer at the AVMA. The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine is also making significant contributions to DEI in veterinary medicine (Burkhard et al. 2022; College of Veterinary Medicine 2019).

The concept of this book is an A–Z guide of terms that relate to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Each chapter can stand on its own, but when taken...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.1.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Veterinärmedizin |

| Schlagworte | access to veterinary medicine • dei in veterinary practice • dei in veterinary research • diversity in vet med • equity in vet med • gender and veterinary medicine • inclusion in vet med • queer veterinary medicine • Veterinary dei • veterinary medicine dei |

| ISBN-10 | 1-394-21710-2 / 1394217102 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-394-21710-6 / 9781394217106 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich