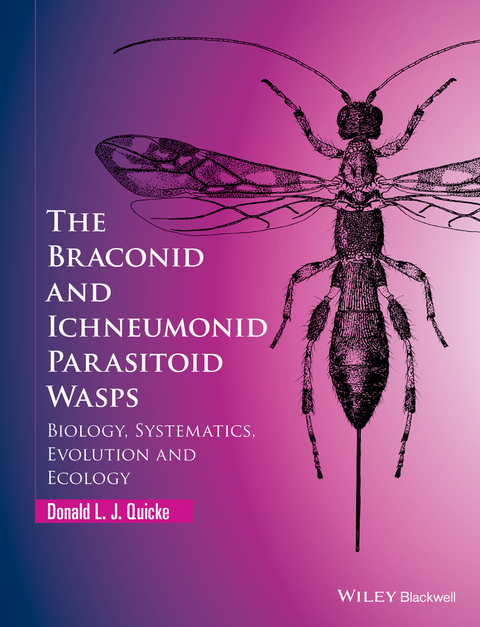

The Braconid and Ichneumonid Parasitoid Wasps (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-90706-1 (ISBN)

The Ichneumonoidea is a vast and important superfamily of parasitic wasps, with some 60,000 described species and estimated numbers far higher, especially for small-bodied tropical taxa. The superfamily comprises two cosmopolitan families - Braconidae and Ichneumonidae - that have largely attracted separate groups of researchers, and this, to a considerable extent, has meant that understanding of their adaptive features has often been considered in isolation. This book considers both families, highlighting similarities and differences in their

adaptations.

The classification of the whole of the Ichneumonoidea, along with most other insect orders, has been plagued by typology whereby undue importance has been attributed to particular characters in defining groups. Typology is a common disease of traditional taxonomy such that, until recently, quite a lot of taxa have been associated with the wrong higher clades. The sheer size of the group, and until the last 30 or so years, lack of accessible identification materials, has been a further impediment to research on all but a handful of 'lab rat' species usually cultured initially because of their potential in biological control.

New evidence, largely in the form of molecular data, have shown that many morphological, behavioural, physiological and anatomical characters associated with basic life history features, specifically whether wasps are ecto- or endoparasitic, or idiobiont or koinobiont, can be grossly misleading in terms of the phylogeny they suggest. This book shows how, with better supported phylogenetic hypotheses entomologists can understand far more about the ways natural selection is acting upon them.

This new book also focuses on this superfamily with which the author has great familiarity and provides a detailed coverage of each subfamily, emphasising anatomy, taxonomy and systematics, biology, as well as pointing out the importance and research potential of each group. Fossil taxa are included and it also has sections on

biogeography, global species richness, culturing and rearing and preparing specimens for taxonomic study. The book highlights areas where research might be particularly rewarding and suggests systems/groups that need investigation. The author provides a large compendium of references to original research on each group. This book is an essential workmate for all postgraduates and researchers working on ichneumonoid or other parasitic wasps worldwide. It will stand as a reference book for a good number of years, and while rapid advances in various fields such as genomics and host physiological interactions will lead to new information, as an overall synthesis of the current state it will stay relevant for a long time.

Donald L. J. Quicke is currently Visiting Professor at the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. He graduated from Oxford University with a degree in zoology and after doctoral and postdoctoral work on snail neurophysiology, sea anemone ecology and spider venoms, made parasitic wasps, and especially the ichneumonoid wasp family Braconidae, his main love and research interest. He held a lectureship at Sheffield University, moved to Imperial College London in 1993 and held a joint post between them and the Natural History Museum, London, until retiring in 2013 to live in Thailand. He was made Professor of Systematics in 2008. He has travelled widely collecting and studying parasitic wasps, especially in Africa. Over the past years he has described more than 560 new species and 76 new genera, including a number of fossil taxa, as well as making extensive studies of functional anatomy parasitic wasp ovipositors which are of enormous biological importance. A lot of his recent work has concerned global diversity estimation and patterns.

The Ichneumonoidea is a vast and important superfamily of parasitic wasps, with some 60,000 described species and estimated numbers far higher, especially for small-bodied tropical taxa. The superfamily comprises two cosmopolitan families - Braconidae and Ichneumonidae - that have largely attracted separate groups of researchers, and this, to a considerable extent, has meant that understanding of their adaptive features has often been considered in isolation. This book considers both families, highlighting similarities and differences in their adaptations. The classification of the whole of the Ichneumonoidea, along with most other insect orders, has been plagued by typology whereby undue importance has been attributed to particular characters in defining groups. Typology is a common disease of traditional taxonomy such that, until recently, quite a lot of taxa have been associated with the wrong higher clades. The sheer size of the group, and until the last 30 or so years, lack of accessible identification materials, has been a further impediment to research on all but a handful of lab rat species usually cultured initially because of their potential in biological control. New evidence, largely in the form of molecular data, have shown that many morphological, behavioural, physiological and anatomical characters associated with basic life history features, specifically whether wasps are ecto- or endoparasitic, or idiobiont or koinobiont, can be grossly misleading in terms of the phylogeny they suggest. This book shows how, with better supported phylogenetic hypotheses entomologists can understand far more about the ways natural selection is acting upon them. This new book also focuses on this superfamily with which the author has great familiarity and provides a detailed coverage of each subfamily, emphasising anatomy, taxonomy and systematics, biology, as well as pointing out the importance and research potential of each group. Fossil taxa are included and it also has sections on biogeography, global species richness, culturing and rearing and preparing specimens for taxonomic study. The book highlights areas where research might be particularly rewarding and suggests systems/groups that need investigation. The author provides a large compendium of references to original research on each group. This book is an essential workmate for all postgraduates and researchers working on ichneumonoid or other parasitic wasps worldwide. It will stand as a reference book for a good number of years, and while rapid advances in various fields such as genomics and host physiological interactions will lead to new information, as an overall synthesis of the current state it will stay relevant for a long time.

Donald L. J. Quicke is currently Visiting Professor at the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. He graduated from Oxford University with a degree in zoology and after doctoral and postdoctoral work on snail neurophysiology, sea anemone ecology and spider venoms, made parasitic wasps, and especially the ichneumonoid wasp family Braconidae, his main love and research interest. He held a lectureship at Sheffield University, moved to Imperial College London in 1993 and held a joint post between them and the Natural History Museum, London, until retiring in 2013 to live in Thailand. He was made Professor of Systematics in 2008. He has travelled widely collecting and studying parasitic wasps, especially in Africa. Over the past years he has described more than 560 new species and 76 new genera, including a number of fossil taxa, as well as making extensive studies of functional anatomy parasitic wasp ovipositors which are of enormous biological importance. A lot of his recent work has concerned global diversity estimation and patterns.

"Overall, this is a highly valuable compendium of known information, as well as currently unanswered questions, concerning ichneumonoid wasps.... Quicke is to be congratulated for producing a standard work that I, for one, will be consulting for a long time." (American Entomologist, 2016)

"This is certainly a field with many pitfalls, but there is hardly a better guide through it than Professor Quicke." (International Journal of Environmental Studies, 9 March December 2015)

"It sounds like a backhanded compliment to say that this is the best book of its kind, when I have already said that it is the only book of its kind. However, The Braconid and Ichneumonid Parasitoid Wasps goes beyond being the best of a limited field - it is a truly impressive assemblage of information on an intriguing and important group of insects. I hope that it inspires more people to work in the field." (Bulletin de la Société d'entomologie du Canada, 2015)

Chapter 1

Introduction

Although most people are blissfully unaware of them, the ichneumonoid wasps are one of the most diverse groups of insects, and in terms of their ecological role they are probably of enormous importance. No-one really has a good idea about how diverse they are and estimates vary widely. The total number of valid species described to date, 18,000 braconids and 23,000 ichneumonids1, is certainly a great underestimate, but by how much is still anyone's guess. Many works cite estimates of 40,000 and 60,000, based upon expert opinion (Townes 1969, Gauld & Bolton 1988). Similar values have also been obtained by various objective estimation measures, but it seems likely that these too are underestimates, and narrowing the numbers down is not going to be easy for the reasons explained in Chapter 15.

Unfortunately, neither family has attracted a lot of attention from amateur entomologists, which seems to be a prerequisite for a good knowledge of a group's taxonomy, distribution and biology. This may be partly because many of the species are rather small and often dull coloured, although this does not seem to have deterred generations of amateur coleopterists. Probably the most important factor has been the dearth, until fairly recently, of reliable and accessible identification guides to the major groups (subfamilies), confounded by the fact that the subfamily-level classification is only now becoming fairly stable, largely as a result of much new molecular work. Problems have been compounded because numerous names were mis-applied by early workers and, as these errors were slowly discovered and corrected, many groups accumulated a historical backlog of alternative names. In many fields of science, the really old literature seldom has to be cited, but in zoology, a great deal of excellent work on anatomy and biology was carried out 50 to 100 or so years ago. As this may be the only detailed work on a given group, it is still relevant today and the reader therefore has to deal with the sometimes confusing or even misleading nomenclature.

Difficulties in the correct identification of specimens, and publications dealing with incorrectly identified specimens, have also been a major stumbling blocks. To quote Perkins (1959), ‘It is perhaps, not surprising that keys to subfamilies are very imperfect, as exceptions can be found to almost all characters that have been used in defining any subfamily, even in the limited British fauna’. Partly because of overall improving taxonomic and systematic understanding, published research on both families is growing, that dealing with the braconids slightly more quickly than that for the ichneumonids (Fig. 1.1). There may be several reasons for this growth, not the least of which is that most researchers are now under great pressure to publish their findings quickly in bite-sized chunks and in high-impact journals, rather than presenting single, large tomes representing the results of many years of their work. The difference in the rate of publication between the families could well be due to the ease of identification – recognising subfamilies is generally easier for braconids and knowing what subfamily you are dealing with is the essential first step towards a proper identification.

Fig. 1.1 Numbers of papers on Braconidae and Ichneumonidae published each year in Science Citation Index (SCI) journals from 1970 to 2012.

The Ichneumonidae and Braconidae are each such large groups that few people since the early 20th century have attempted to work seriously on the whole of either one of them, so it is hardly surprising that in recent years almost no-one has attempted to tackle them both. This, of course, means that the similarities and differences between them may have been less well considered than they should have been. Superficially, it might seem that these two families essentially parallel one another, they are sister groups and they broadly occupy the same range of niches—they predominantly parasitise exposed and concealed moth and beetle larvae with a few incursions into attacking fly and Hymenoptera larvae, rarer ones into other insect groups and a few other ways of life such as spider egg predation and even a few instances of true phytophagy. However, things may not be as simple as they seem, because despite some remarkable parallels, they also show strong group differences in precisely what they do and in the types of adaptations they typically employ.

It should come as no surprise therefore, that ichneumonids and braconids do not ‘behave’ in the same way in so many aspects of their biology and morphology. If they did, it seems likely that one would have driven the other to extinction or pushed them a long way in that direction. That both groups are highly speciose seems very likely to indicate that they do not compete in a precise and consistent way, although many individual species no doubt do. Hence there are various sorts of adaptations that appear to evolve frequently in one family but not or only rarely in the other. For example, numerous braconids have evolved carapace-like metasomas where the basal 3 (or sometimes 4) metasomal terga are enlarged, frequently fused, or at least more or less immovably joined and conceal all more posterior ones (see Chapter 10, section Carapacisation). Only a very few ichneumonid groups have members with carapaces and the numbers of species involved is very small. Is this associated with the difference in articulation between the second and third metasomal terga, which is one of the diagnostic features for separating the two families? Endoparasitoid larvae belonging to several different braconid lineages have apparently independently evolved an everted rectum forming a structure called an anal vesicle (see Fig. 5.1) that serves a variety of physiological roles, but this adaptation, as far as is known, has only evolved in two genera within the Ichneumonidae. Similarly, very elongate mouthparts (although variously involving the glossa, malar region or maxillary palps) have evolved on numerous independent occasions within those Braconidae dwelling in relatively arid habitats (see Chapter 10, section Concealed nectar extraction apparatus), but the number of such occurrences in the Ichneumonidae is small (e.g. Rhynchobanchus: Banchinae). These modified mouthparts, collectively referred to as a concealed nectar extraction apparatus, are an adaptation to obtain nectar from plants such as Asteraceae or Dipsaciaceae, which in turn are adapted to prevent their nectar from drying up in places where water is in short supply. In this case, it may be because braconids tend to comprise a relatively larger proportion of species in such habitats, but the data are not really available to test this.

Ichneumonids collectively utilise a somewhat different spectrum of hosts than braconids. They include many more taxa that are parasitoids of other Hymenoptera, including both endo- and ectoparasitism, in addition to acting as pseudohyperparasitoids of other ichneumonoids (see Fig. 13.1; cf. Fig. 12.2), and endoparasitism including developing as true hyperparasitoids within a host, as well as some being predators within aculeate wasp and bee nests. In the Braconidae, members of two tribes within the Euphorinae are endoparasitoids on adult Hymenoptera, a few ectoparasitoids attack leaf-mining sawflies and only a few members of the Ichneutinae are endoparasitic within sawfly larvae, and Gauld (1988a) plausibly suggested that these made the transition to sawfly hosts from ancestors that were endoparasitoids of leaf-mining Lepidoptera. Further, no braconids apart from the rather special case of a few euphorines parasitising adult ichneumonoids (see Chapter 12, section Syntretini), no braconids are hyperparasitoids or even pseudohyperparasitoids. Two subfamilies within Ichneumonidae, involving several evolutionary transitions, have become associated with spiders either as egg predators or as parasitoids of juvenile and adult individuals. All of these seem to be connected by their use of silk, or volatile or non-volatile compounds associated with silk, in the host location – because of its non-solubility, silk proteins themselves seem an incredibly unlikely source of host-finding cues. Nevertheless, at least some braconids do utilise cues from host silk trails (Ha et al. 2006), but it does not seem to have become an important part of their behavioural repertoire. Perhaps partly associated with this and the places where silk-cocooned hosts occur, ichneumonids appear to have evolved vibrational sounding (a sort of echolocation) as a host location tool on multiple occasions (and lost it on many also), whereas there is no evidence for this host location mode in the Braconidae (see Chapter 10, section Antennal hammers and vibrational sounding).

Another important question that we ought to consider is why the ichneumonoids and chalcidoids have not out-competed one another in one direction or another. Some niches occupied by chalcidoids are not available to ichneumonids; for example, egg parasitism, which necessitates body sizes smaller than or at least at the very bottom range of that which ichneumonoids (e.g. Miracinae or Cheloninae–Adeliini) have thus far achieved. Ichneumonids described to date are, in general, larger bodied than braconids (see Fig. 15.6), and this may correlate with some differences in host utilisation, since only braconids can attack small insect hosts such as psocids, aphids, plant bugs and tiny beetles (Čapek 1970).

It seems to me a very great shame that...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.12.2014 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Zoologie |

| Technik | |

| Veterinärmedizin | |

| Schlagworte | Ãkologie / Tiere • Animal ecology • Animal Science & Zoology • biodiversity • Biological Control • Biowissenschaften • Braconidae • classification • Development • Ecology • Entomologie • Entomology • Evolution • Ichneumonidae • Life Sciences • Morphology • Ökologie / Tiere • Systematics • Zoologie |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-90706-X / 111890706X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-90706-1 / 9781118907061 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich