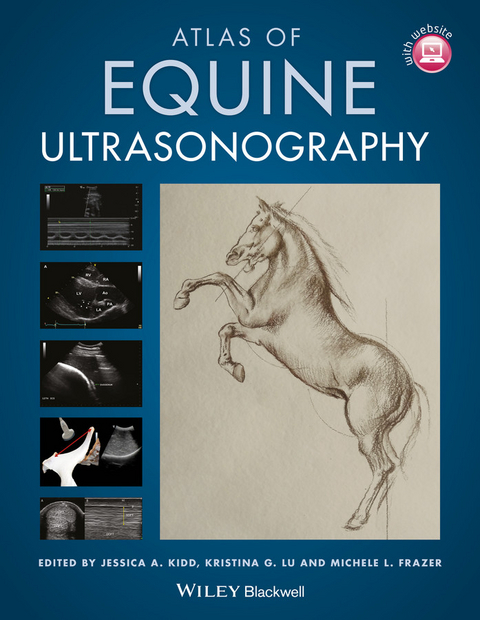

Atlas of Equine Ultrasonography (eBook)

520 Seiten

Wiley-Blackwell (Verlag)

9781118798126 (ISBN)

The only visual guide to equine ultrasonography based on digital ultrasound technology. Atlas of Equine Ultrasonography provides comprehensive coverage of both musculoskeletal and non-musculoskeletal areas of the horse. Ideal for practitioners in first opinion or referral practices, each chapter features normal images for anatomical reference followed by abnormal images covering a broad range of recognised pathologies. The book is divided into musculoskeletal, reproductive and internal medicine sections and includes positioning diagrams demonstrating how to capture optimal images. With contributions from experts around the world, this book is the go-to reference for equine clinical ultrasonography.

Key features include:

- Pictorially based with a wealth of digital ultrasound images covering both musculoskeletal and non-musculoskeletal areas and their associated pathologies.

- Each chapter begins with a discussion of normal anatomy and demonstrates how to obtain and interpret the images presented.

- A video library of over 50 ultrasound examinations is available for streaming or download and viewing on-the-go. Access details are provided in the book.

Jessica A. Kidd, BA, DVM, CertES(Orth), Dipl. ECVS, MRCVS is an RCVS and European Recognised Specialist in Equine Surgery based in Oxfordshire, UK.

Kristina G. Lu, VMD, Dipl. ACT is a specialist in equine reproduction at Hagyard Equine Medical Institute, Lexington, Kentucky, USA.

Michele L. Frazer, DVM, Dipl. ACVIM ACVECC is a specialist in equine internal medicine and emergency and critical care medicine at Hagyard Equine Medical Institute, Lexington, Kentucky, USA.

Jessica A. Kidd, BA, DVM, CertES(Orth), Dipl. ECVS, MRCVS is an RCVS and European Recognised Specialist in Equine Surgery based in Oxfordshire, UK. Kristina G. Lu, VMD, Dipl. ACT is a specialist in equine reproduction at Hagyard Equine Medical Institute, Lexington, Kentucky, USA. Michele L. Frazer, DVM, Dipl. ACVIM ACVECC is a specialist in equine internal medicine and emergency and critical care medicine at Hagyard Equine Medical Institute, Lexington, Kentucky, USA.

List of Contributors ix

About the Companion Website xi

Introduction 1

Kimberly Palgrave and Jessica A. Kidd

Section 1 Musculoskeletal

1. Ultrasonography of the Foot and Pastern 25

Ann Carstens and Roger K.W. Smith

2. Ultrasonography of the Fetlock 45

Eddy R.J. Cauvin and Roger K.W. Smith

3. Ultrasonography of the Metacarpus and Metatarsus 73

Roger K.W. Smith and Eddy R.J. Cauvin

4. Ultrasonography of the Carpus 107

Ann Carstens

5. Ultrasonography of the Elbow and Shoulder 125

Barbara Riccio

6. Ultrasonography of the Hock 149

Katherine S. Garrett

7. Ultrasonography of the Stifle 161

Eddy R.J. Cauvin

8. Ultrasonography of the Pelvis 183

Marcus Head

9. Ultrasonography of the Neck and Back 199

Marcus Head

10. Ultrasonography of the Head 213

Debra Archer

Videos: Dynamic Ultrasonography of Musculoskeletal Regions

225

Sarah Boys Smith

Section 2 Reproduction

Section 2a: Ultrasonography of the Stallion Reproductive

Tract

11. Ultrasonography of the Internal Reproductive Tract 241

Malgorzata A. Pozor

12. Ultrasonography of the Penis 267

Malgorzata A. Pozor

13. Ultrasonography of the Testes 277

Charles Love

Section 2b: Ultrasonography of the Mare Reproductive Tract

14. Use of Ultrasonography in the Evaluation of the Non-Pregnant

Mare 291

Walter Zent

15. Use of Ultrasonography in the Management of the Abnormal

Broodmare 297

Jonathan F. Pycock

16. Transrectal Ultrasonography of Early Equine Gestation

- the First 60 Days 309

Christine Schweizer

17. Use of Ultrasonography in Twin Management 323

Richard Holder

18. Use of Ultrasonography in Equine Fetal Sex Determination

Between 55 and 200 Days of Gestation 329

Richard Holder

19. Use of Ultrasonography in Fetal Development and Monitoring

341

Stefania Bucca

20. Ultrasonography of the Post-Foaling Mare 351

Peter R. Morresey

Section 3 Internal Medicine

Section 3a: Ultrasonography of the Thoracic Cavity

21. Ultrasonography of the Pleural Cavity, Lung, and Diaphragm

367

Peter R. Morresey

22. Ultrasonography of the Heart 379

Colin C. Schwarzwald

Section 3b: Ultrasonography of the Abdominal Cavity

23. Ultrasonography of the Liver, Spleen, Kidney, Bladder, and

Peritoneal Cavity 409

Nathan Slovis

24. Ultrasonography of the Gastrointestinal Tract 427

Fairfield T. Bain

Section 3c: Ultrasonography of Small Structures

25. Ultrasonography of the Eye and Orbit 445

Caryn E. Plummer and David J. Reese

26. Ultrasonography of the Soft Tissue Structures of the Neck

455

Massimo Magri

27. Ultrasonography of Vascular Structures 475

Fairfield T. Bain

28. Ultrasonography of Umbilical Structures 483

Massimo Magri

Index 495

"The use of photographs of anatomic specimens and novel CT reconstructions with overlays to depict probe positioning provides excellent guidance for both novice and experienced sonographers." (JAVMA, 15 December 2014)

Introduction

Kimberly Palgrave1 and Jessica A. Kidd2

1Overland Animal Hospital, Denver, CO, USA; 2Oxfordshire, UK

Welcome to the first edition of the Atlas of Equine Ultrasonography.

The field of veterinary ultrasonography has blossomed in the last 30 years and the improvements in technology since its first use have been exponential. It is also now being used on structures and body systems that were not previously thought to be conducive to ultrasonography. Many vets in equine practice now have access to an ultrasound machine and, along with radiography, ultrasonography has become a mainstay of equine diagnostic imaging. It has the advantages of being non-invasive and complementary to radiography. The purpose of this book is to encourage further use of ultrasonography in clinical case management and expansion of the techniques utilized by vets in both general practice and at the referral level.

Ultrasonography is an excellent diagnostic tool which has many applications in veterinary practice. When considered in conjunction with relevant clinical information, such as patient history and physical examination findings, it can be an extremely useful aid in the clinical decision-making process. Developing the skills necessary to confidently acquire and interpret ultrasound images requires knowledge of normal equine anatomy and an understanding of the mechanisms displayed by individual body systems when reacting to various disease processes. We hope this book will help achieve this. A general appreciation of the physics of ultrasound is also necessary as this enables the ultrasonographer to optimize the diagnostic quality of ultrasound images obtained by appropriately altering their technique and machine settings. The aim of this introductory chapter is to provide an overview of ultrasound technology and the fundamental principles of image evaluation with a focus on the applications of ultrasound within equine practice.

How to Use This Book

The book is divided into three main sections: musculoskeletal, reproduction, and internal medicine. Each section is then further subdivided into chapters by anatomical region. Within each chapter is information on scanning technique for that area, a review of the normal anatomy and discussion of some of the more common ultrasonographic abnormalities. This is then followed by images that demonstrate normal and abnormal findings. The end of each chapter lists Recommended Reading for more extensive references relating to the chapter topics.

Physics of Ultrasound

Ultrasound physics is a vast and theoretically complex subject; however, a thorough understanding of this topic is not required for performing and utilizing diagnostic ultrasonography effectively in the clinical environment. Therefore, this text will cover the aspects of ultrasound physics that directly relate to the interaction of ultrasound waves with tissue and how these interactions translate to the displayed image. Additional sources covering this subject matter in greater detail are listed at the end of this chapter under Recommended Reading.

Features of Ultrasound Waves

Ultrasound waves have features in common with audible sound waves although they are of a higher frequency than audible sound and cannot be heard by the human ear; hence the term ultrasound. They are both created through the vibration of an object resulting in movement of surrounding molecules. Ultrasound waves are produced through the application of an electric current to piezoelectric crystals within the transducer (probe), causing the crystals to vibrate. This vibration is transmitted through the surrounding tissues in the form of sound waves. These waves interact with the tissues along their path of travel in various ways which may result in attenuation of the ultrasound beam.

Attenuation is defined as the progressive weakening in intensity of the ultrasound wave as it is transmitted through body tissues. Sound waves passing through tissues can either be reflected, refracted, scattered or absorbed. These are the primary causes of attenuation of the ultrasound wave and these phenomena are ultimately responsible for the formation of an ultrasound image.

Reflection and Acoustic Impedance

As ultrasound waves travel through the body, they come into contact with structures which reflect a proportion of the waves directly back towards the piezoelectric crystals, while the remainder of the waves continue to travel deeper into the tissues. The force of the returning waves or echoes results in vibration of the crystals and this vibration is then translated into an electrical signal, which is used to create the image displayed on the screen. Therefore, a unique feature of piezoelectric crystals is that they are capable of both emitting and receiving ultrasound waves.

It is important to realize that an ultrasound image is only produced when ultrasound waves are reflected back to the transducer. Reflection occurs when an ultrasound wave reaches an interface between two tissues as it is transmitted through the body and a portion of that wave is returned or “bounced back” to the probe while the remainder of the wave continues to travel deeper into the body. The strength of the returning wave and the length of time taken for that wave to travel through the tissues before returning to the probe is recognized and processed by the ultrasound machine in order to create the ultrasound image. These concepts will be later explored in the B-Mode and Echogenicity section.

The proportion of the emitted wave that is reflected back to the probe depends on the acoustic impedance of the interface between tissues and the angle at which the ultrasound wave strikes the interface. The acoustic impedance of a tissue is a product of the density of that tissue and the speed at which sounds waves travel through it. A dense tissue, such as bone, has a high acoustic impedance (7.8) compared to the relatively low acoustic impedance of air (0.0004), with soft tissues being in between (kidney – 1.62) (see Table I.1). However, it is the difference in acoustic impedance between tissue types that determines the reflective nature of a given tissue interface, not the acoustic impedance of a single tissue in isolation. For example, both a bone–soft tissue interface and an air–soft tissue interface have significant differences between the acoustic impedance values of the tissues at that interface, despite the fact that bone and air are at opposite ends of the acoustic impedance spectrum. Therefore, both bone–soft tissue and air–soft tissue interfaces are highly reflective, with the majority of the ultrasound waves being reflected back to the transducer in both scenarios. This also results in very little of the ultrasound wave remaining to penetrate into the deeper tissues beyond this highly reflective interface. By comparison, soft tissue–soft tissue interfaces (either between or within soft tissue structures) are less reflective due to the small differences between the acoustic impedances of these tissue types. Understanding this physical property of ultrasound wave propagation is essential to understanding how tissue variations translate into the ultrasound image appearance. This also justifies the need for appropriate patient preparation, including clipping of the haircoat where possible and application of ultrasound coupling gel to minimize the amount of air at the probe–skin interface. Differences in acoustic impedance also contribute to artifact formation, which will be discussed later in the chapter.

Table I.1 Approximate acoustic impedance in commonly encountered tissues. (Source: Adapted from Curry, TS III et al., 1990. Reproduced with permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.)

| Tissue | Acoustic impedance (in 106 Rayls) |

|---|

| Air | 0.0004 |

| Fat | 1.38 |

| Water (50°C) | 1.54 |

| Brain | 1.58 |

| Blood | 1.61 |

| Kidney | 1.62 |

| Liver | 1.65 |

| Muscle | 1.70 |

| Lens of eye | 1.84 |

| Bone (skull) | 7.80 |

The angle at which the ultrasound beam strikes the tissues is also integral to the degree of reflection of the ultrasound wave. Only ultrasound waves striking an interface which is perpendicular to the direction in which the wave is travelling will result in reflection of the wave directly back to the probe. If the wave reaches the tissue interface at an angle, the waves will be reflected into adjacent tissues instead of back to the probe, resulting in a lack of direct information from that area of the body. Therefore, the true reflective nature of that particular tissue will not be accurately represented in the displayed ultrasound image. In practical terms, imaging a structure when the ultrasound beam is not directed perpendicular to the region of interest may result in a smaller proportion of the wave being reflected to the probe and the resulting ultrasound appearance of that structure may appear “patchy” or irregular, although this effect can be used to the ultrasonographer's advantage, by allowing the margins of structures to be more easily recognized, for example.

Refraction, Scatter, and Absorption

In addition to reflection, other types of interaction between the ultrasound beam and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 19.3.2014 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Medizin / Pharmazie |

| Veterinärmedizin ► Großtier | |

| Veterinärmedizin ► Pferd | |

| Schlagworte | abnormal • anatomical • Areas • Comprehensive • digital • Equine • features • First • Guide • horse • Ideal • Musculoskeletal • nonmusculoskeletal • opinion • Pferd • Practices • Practitioners • provides • Referral • Technology • Ultraschalldiagnostik • ultrasonography • Ultrasound • Veterinärmedizin • Veterinärmedizin / bildgebende Verfahren • Veterinärmedizin f. Pferde • Veterinärmedizin • Veterinärmedizin / bildgebende Verfahren • Veterinärmedizin f. Pferde • Veterinary Imaging • Veterinary Medicine • Veterinary Medicine - Equine • Visual |

| ISBN-13 | 9781118798126 / 9781118798126 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: PDF (Portable Document Format)

Mit einem festen Seitenlayout eignet sich die PDF besonders für Fachbücher mit Spalten, Tabellen und Abbildungen. Eine PDF kann auf fast allen Geräten angezeigt werden, ist aber für kleine Displays (Smartphone, eReader) nur eingeschränkt geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich