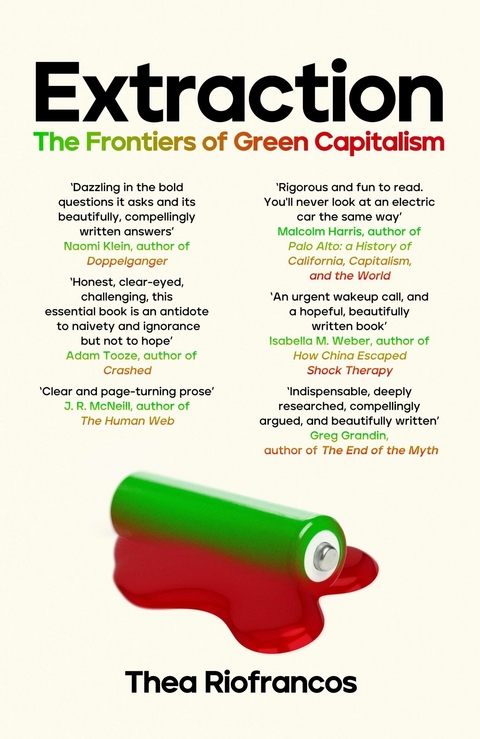

Extraction (eBook)

320 Seiten

Icon Books (Verlag)

978-1-83773-270-8 (ISBN)

Thea Riofrancos has been featured in Granta, the Guardian, the Financial Times, the New York Times and the Washington Post. She is a political science professor at Providence College, and a strategic codirector of the Climate and Community Institute. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island.

PROLOGUE

Mining Water in a Desert

A high-altitude desert plateau traverses Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile. I am on the Chilean side, in the passenger seat of a Jeep, along with two other researchers. The afternoon air is thin and brisk, but the sun is piercing—a combination I am familiar with from years of living and traveling in South America’s Andean range. The landscape is a study in contrasts and contours: broad basins suddenly cut off by sweeping curves, flat expanses sliced by near vertical ascents. The Licancabur Volcano looms large above us. Vegetation and humidity levels change rapidly with the rising altitude, bringing cooler temperatures, wetter air, and denser plant life. We are driving from San Pedro, once a small town but now a metastasizing tourist hub, to the Salar de Atacama, the vast salt flats that contain the largest lithium reserves in the world.1

The space and time of our journey are occasionally marked by passing through one or another of the eighteen Indigenous (Atacameño, or Lickanantay) communities that ring the salt flat, each organized around one of the spring-fed streams that run down the deep ravines sliced into the slopes of the surrounding mountains. Each community has a relationship to its deified and named mountain, which a range of practices aim to appease in return for water and harvests. Local irrigation infrastructures channel this water to homes and small farms. The resulting “Mediterranean” microclimate creates fertile conditions for figs, pomegranates, quince, grapes, and maize.

We detour into the high mountains bordering Bolivia before careening back down toward the alluvial basin and the salar. En route, we pass an Atacameño family in the midst of an outdoor celebration. I buy a kilogram of fresh goat cheese, and then we take off for the salt flat.

A sandstorm, improbably though quite palpably interspersed with a rainstorm, engulfs us for most of the remainder of our drive. I’m not sure if I’ve ever felt so buffeted by so many elements at once: the whipping wind, the sky alternately grainy with sand and sparkling with raindrops, intense sunlight barely veiled by enormous gray clouds. And then, abruptly, the environment rearranges itself. The sand and sandstorm disappear, replaced by gradations of white and gray that stretch all the way to the mountains that still form the horizon.

This is the Salar de Atacama—the Atacama Salt Flat—the largest of several dozen salt flats in northern Chile and the third largest in the world, about two-thirds the size of my home state of Rhode Island. The brilliant white flat lies in a high basin 7,500 feet above sea level, enclosed by the even higher Andean Mountains to the east and the Domeyko Mountains to the west. We park and enter Los Flamencos National Reserve, 285 square miles of protected ecosystem, by foot. It is extremely dry and the solar radiation extremely high (the day we visited the UV levels were literally off the charts). To our left stretches unending salt crust. To our right, the crust is interspersed with lagoons. But the landscape is not all gray and white. Upon closer inspection, elegant Andean flamingos with pastel pink feathers are backed by the muted red water of the lagoons, an effect produced by the interaction of algae, sun, and wind.

This striking landscape—the salt flat, the flamingos, and the neighboring Indigenous communities—is under threat from a counterintuitive source: our efforts to save the planet from catastrophic climate change. Just beneath my feet are nearly one-third of the world’s lithium reserves, suspended in water saltier than the ocean.2 Lithium is essential to addressing the climate crisis. It is a key ingredient in the rechargeable batteries that play a starring role in eliminating carbon emissions from transportation and energy—the two highest emitting sectors. But extracting this lithium will come at escalating social and environmental costs. It is this dilemma that has brought me to the salt flat.

THE ATACAMA IS THE WORLD’S OLDEST DESERT. THE HIGH-ALTITUDE, bone-dry landscape, with its dazzling days and spectacularly starry nights, formed twenty million years ago. And despite forbidding conditions, humans began living in the Atacama at least eleven or twelve thousand years ago.3 Nor were they isolated. The Andean plateau long enabled north-south movement, and by at least fifteen hundred years ago, the settlements of the plateau had become intensively linked by networks of trade and travel across the Domeyko Mountains’ passes with those of the more hospitable Pacific coastal plain.

But those more interested in the region’s minerals than its people or ecology have repeatedly declared it to be empty and lifeless. The narrative penned by Spanish historian Jerónimo de Vivar, who accompanied the conquistador Pedro de Valdivia in the 1540s, painted an enduring portrait of the landscape as “barren” and “unpopulated,” except for the valleys. In all of this expanse, he wrote, “it does not rain.”4 The winds were frigid, the risk of death by thirst palpable. Accordingly, Vivar called the vast space “el gran despoblado.” In Spanish, the word despoblado is ambiguous. It can mean simply unpopulated, or it can mean depopulated, implying a change over time.5 A deserted desert, in other words.

To the Spanish, this imagined emptiness justified their colonial domination. After independence in 1818, Chilean authorities appointed experts to explore and map the region and to assess the desert’s “economic potential”—specifically, its “mineable wealth.”6 They reproduced the tropes of colonial conquest, emphasizing the same extreme aridity, hostility to life, and emptiness.7 They urged the state to provide support for private firms to exploit the riches of this ostensible terra nullius—and it did.

Government policies encouraged resource extraction, which then incentivized more government support, in an accelerating cycle. In 1858, because of the discovery of copper nearby, the government declared the fishing village of Taltal a state harbor.8 Railroads would later link it to new inland nitrate mines, confirming it as the coastal logistical hub of multiplying extractive spokes. The state built an elaborate system of wells and pipelines to provide crucial water access for mining operations. The legal infrastructure of Chile’s Mining Code of 1874 further facilitated the private appropriation of subsoil wealth. By the late nineteenth century, silver, gold, copper, and nitrate production was booming. Over a century later, the state still depends on the revenues generated by mining and is looking toward its next resource boom.

Today the Atacama Desert is best known as an extractive frontier, rich in two minerals key to the energy transition: lithium and copper. Abundant in resources—but supposedly devoid of life. Wealth, free for the taking, with purportedly no one and nothing harmed in exchange. State and capital, scientists and maps, minerals and water, laws and property rights, pipes and ports . . . and narratives that erase thousands of years of human habitation and flatten a complex ecosystem into a lifeless blank slate. This is how extractive frontiers are made.

WHEN IT DOES RAIN IN THE ATACAMA, IT’S HARD TO OVERSTATE the intensity of the floods. I once found myself caught in what is called invierno boliviano, or Bolivian winter, a paradoxical name for a weather phenomenon that occurs during the Southern Hemisphere’s summer months. These rainy fronts originate in the Amazon and travel up the steep slopes of the Andean Mountains, where Bolivia’s high-altitude winds then drive them up and over the ridges, until their torrents drench the Chilean high plateau.

Rainbows were the first sign that precipitation was making its way toward us. I was on a guided trek with a group of tourists, walking on the path along a narrow ridge in el Valle de la Luna (the Valley of the Moon), trying to keep from falling over the steep cliffs on either side while gazing up at the deep red, undulating mountains and impossibly smooth sand dunes. Suddenly, multicolored banners appeared in the sky, one after the other, tracing myriad arcs from peak to peak. There were so many rainbows, I lost track trying to count them. The enchantment was dizzying. But by the time we had driven back to San Pedro de Atacama, the landscape was shrouded in rain. Our preparations for the dry heat, our sunglasses and water bottles, suddenly seemed absurd. The town itself was submerged in darkness—the rain and winds had cut the power supply. We ate by candlelight, still shivering in our damp clothes.

The morning’s light revealed the damage. All roads south of Toconao, an Atacameño village 20 miles from San Pedro, were closed. The desert grasses of the alluvial plain to the left of the road, like the jaunty tufts of gold-green paja brava, were completely submerged. The water, made dark by the sediment it carried, was still rushing past, even though it was no longer raining.

My plans to visit a lithium mining operation foiled by the flooding, I entered Toconao instead. The river running through the town was the main attraction. Here, high up on the Andean plateau, rivers form the centerpieces to ancestral irrigation systems. They are literal oases: You can spot a village from miles away by the cluster of green trees standing out against the otherwise muted tones of the surrounding landscape. On that day, the river ran so high, swirling with white rapids, that the residents had closed all...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.9.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Technik ► Umwelttechnik / Biotechnologie |

| Wirtschaft ► Volkswirtschaftslehre | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83773-270-1 / 1837732701 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83773-270-8 / 9781837732708 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich