How Your House Works (eBook)

461 Seiten

Rsmeans (Verlag)

978-1-394-21333-7 (ISBN)

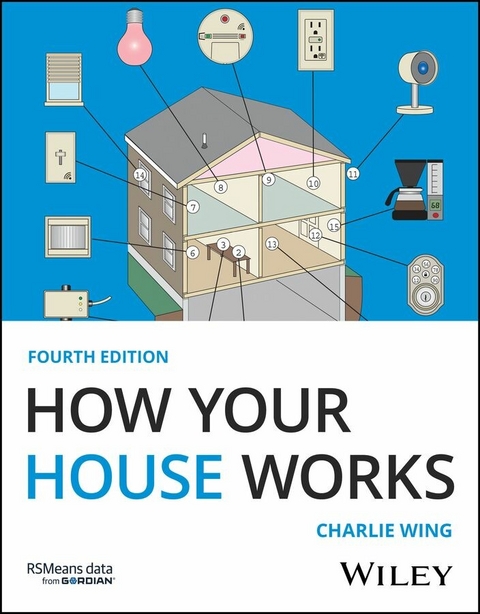

FIX IT. MAINTAIN IT. UNDERSTAND IT. THE LATEST EDITION OF THE BESTSELLING VISUAL GUIDE FOR ALL HOMEOWNERS.

Most people will never make a more important purchase than a house; properly understanding and maintaining your home can be a fundamental component of a financially sound life. Most homeowners, however, rely on contractors and building engineers to understand the systems that comprise a modern home. There is an urgent need for a guide which makes these essential systems transparent to the general consumer.

How Your House Works provides a working overview of all the basic systems that make up your home, from electrical systems to HVAC to plumbing and beyond. Richly illustrated and with clear, accessible language, this book demystifies the foundations of home ownership and puts you in control of the structures that make your house work.

Readers of the fourth edition of How Your House Works will also find:

- New chapters on household batteries

- Expanded sections pertaining to smart home technology and sustainability

- Detailed, full-color illustrations by the author

How Your House Works is a must-have for any homeowner or prospective buyer.

Charlie Wing, PhD, is a nationally recognized authority on home rebuilding, remodeling, repair, and energy conservation. He has been a Principal Investigator in NASA's Apollo Lunar Program and a Physics Instructor at Bowdoin College, cofounded the first two owner-builder schools in the USA, and hosted a PBS national TV series called Housewarming with Charlie Wing. He has published numerous books on home ownership and home repair.

FIX IT. MAINTAIN IT. UNDERSTAND IT. THE LATEST EDITION OF THE BESTSELLING VISUAL GUIDE FOR ALL HOMEOWNERS. Most people will never make a more important purchase than a house; properly understanding and maintaining your home can be a fundamental component of a financially sound life. Most homeowners, however, rely on contractors and building engineers to understand the systems that comprise a modern home. There is an urgent need for a guide which makes these essential systems transparent to the general consumer. How Your House Works provides a working overview of all the basic systems that make up your home, from electrical systems to HVAC to plumbing and beyond. Richly illustrated and with clear, accessible language, this book demystifies the foundations of home ownership and puts you in control of the structures that make your house work. Readers of the fourth edition of How Your House Works will also find: New chapters on household batteriesExpanded sections pertaining to smart home technology and sustainabilityDetailed, full-color illustrations by the author How Your House Works is a must-have for any homeowner or prospective buyer.

1

PLUMBING

If you are like most homeowners, the maze of hot and cold supply pipes and waste pipes in your basement resembles nothing more meaningful than a plate of spaghetti. This chapter will show you that, in fact, your house contains three separate systems of pipes, all making perfect sense.

Understanding their purpose and how each one works will enable you to decide which projects are in the realm of a homeowner, and which ones require a plumber. If you're planning to build a new home or do major remodeling, this chapter will also help you to visualize the plumbing requirements, and how they'll fit into your space.

A visit to the plumbing aisle of your local home center will show you that do-it-yourself plumbing repair has never been easier. There you will find kits, including illustrated instructions, for just about every common repair project.

Plumbing is not dangerous, unless you're dealing with gas pipes. In fact, call a licensed professional if your repair or installation involves any change to existing gas piping. But plumbing mistakes can be damaging to the finishes and contents of your home, just by getting them wet. The force and weight of water are also something to be reckoned with, if many gallons flow where they should not. Before starting a project involving the supply system, locate the shut-off valve for the fixture you're working on. If you can't find one, shut off the main valve where the supply enters the house.

The Supply System

How It Works

The supply system is the network of pipes that delivers hot and cold potable water under pressure throughout the house.

- Water enters underground from the street through a ¾ or 1" metal pipe. In houses built prior to 1950, the metal is usually galvanized steel; after 1950, copper. In the case of a private water supply, the pipe is usually polyethylene.

- If you pay for water and sewage, your home's usage is measured and recorded as the water passes through a water meter. If you find no meter inside the house, one is probably located in a pit between the house and the street. You can monitor your consumption, measured in cubic feet, by lifting the cap and reading the meter.

- Next to the water meter (before, after, or both), you will find a valve, which allows shutting off the water supply, both cold and hot, to the entire house. If you have never noted this valve, do so now. When a pipe or fixture springs a leak, you don't want to waste time searching for it.

- Water heaters are most often large, insulated, vertical tanks containing from 40 to 120 gallons. Cold water enters the tank from a pipe extending nearly to the tank bottom. Electric elements, a gas burner, or an oil burner heat the water to a pre-set temperature. When hot water is drawn from the top, cold water flows in at the bottom to replace it.

If the home is heated hydronically (with circulating water), the water heater may consist of a heat-exchange coil inside the boiler, or it may be a separate tank (BoilerMate™) heated with water from the boiler through a heat exchange coil.

Wall-mounted tankless water heaters provide a limited, but continuous, supply of hot water through a coil heated directly by gas or electricity.

- Supply pipes—both cold and hot—that serve many fixtures are called “trunk lines,” and are usually ¾ in diameter. Pipes serving hose bibbs and other fixtures with high demands may be ¾ as well.

- Pipes serving only one or two fixtures are called “branch lines.” Because they carry less water, they are often reduced in size to ½ and, in the case of toilets, ⅜. Exceptions are pipes serving both a shower and another fixture.

- Every fixture should have shutoff valves on both hot and cold incoming supplies. This is so that repairing the single fixture doesn't require shutting off the entire house supply at the meter valve.

- A pressure-balanced anti-scald valve or thermostatic temperature control valve prevents the hot and cold temperature shocks we have all experienced when someone suddenly draws water from a nearby fixture. They are not inexpensive, but they provide insurance against scalds and cold-water shocks, which may trigger a fall in the elderly.

- “Fixture” is the generic plumbing term for any fixed device that uses water.

Drain pipes are sized according to the rate of flow they may have to carry. One fixture unit (FU) is defined as a discharge rate of one cubic foot of water per minute. Plumbing codes assign bathroom sinks (lavatories) 1 FU, kitchen sinks 2 FU, and toilets (water closets) 4 FU.

The Waste System

How It Works

The waste system is the assemblage of pipes that collects and delivers waste (used) water to either the municipal or private sewage system.

- The pipe that drains away a fixture's waste water is its drain. The minimum diameter of the drain is specified by code and is determined by the rate of discharge of the fixture.

- Each and every fixture drain must be “trapped.” A trap is a section of pipe that passes waste water, but retains enough water to block the passage of noxious sewer gases from the sewage system into the living spaces of the house.

- Toilets (water closets) have no visible trap, but one is actually there, built into the base of the toilet.

- The horizontal section of drain pipe between the outlet of a trap and the first point of the drain pipe that is supplied with outdoor air is called the “trap arm.” The plumbing code limits the length of the trap arm in order to prevent siphon action from emptying the trap. The allowed length is a function of pipe diameter.

- As with a river, the smaller tributary drain pipes that feed into the main “house drain” are called “branches.”

- The largest vertical drain pipe, extending from the lowest point through the roof, and to which the smaller horizontal branch drains connect, is called the “soil stack.” The term “soil” implies that the drain serves human waste. If it does carry human waste, and/or if it serves enough fixture units, it must be at least 3 inches in diameter. In a very horizontally extended house, there may be more than one soil stack.

- The largest, bottom-most horizontal waste pipe is the “house drain.” In a delicate balance between too-slow and too-rapid flow of waste, the house drain (and all other horizontal waste pipes) must be uniformly inclined at between 1/8" and 1/4" per foot. In a basement or crawl space, the house drain is usually exposed. With a slab-on-grade foundation, the house drain is beneath the slab.

- To facilitate unclogging of drain pipes, Y-shaped “cleanouts” are provided. At a minimum, there will be a 4" diameter cleanout at the point where the house drain exits the building. This cleanout is utilized when tree roots invade the exterior drains and special drain-reaming equipment must be called in to cut the roots. Additional cleanouts are required throughout the waste system for every 100' of horizontal run and every cumulative change of direction of 135 degrees.

- Waste pipe outside of the building line is termed the “house sewer.” It is always at least 4" in diameter.

The Vent System

How It Works

As you can see on pages 18 and 19, fixture drains must be kept at atmospheric pressure so that the water seals in their drain traps are not siphoned away, thereby exposing the interior of the house to noxious sewer gases. The vent system consists of the pipes that relieve pressure differences within the drain system.

- All plumbing fixtures (things that use and discharge waste water into the drain system) possess traps. To prevent waste water from forming a siphon during discharge, air must be introduced into the drain pipe near the outlet of the trap (maximum distance determined by the drain pipe diameter).

- The primary vent is part of a large-diameter vertical pipe termed the “stack.” Below the highest point of waste discharge into it is the “waste stack.” Above that point it is the “vent stack.” If a waste stack also serves one or more toilets (and it usually does), it is sometimes called the “soil stack.” Because it provides a direct air passage to the municipal sewer pipe or private septic tank, a vent stack must be terminated in the open air. And to keep the sewer gas as far as possible from people, it is usually terminated through the roof.

- The permitted length of drain pipe from a trap to a vent (the trap arm) is specified by code as a function of the pipe diameter. (See page 19.) If the horizontal run of the drain is very long, a smaller-diameter vent stack is usually provided close after the trap.

- Another solution to the too-long horizontal drain is to break it into legal lengths with “revents.” To guarantee that they are never blocked with water, revents connect to the vent stack at least 6" above the flood level of the highest fixture on the drain. A horizontal drain may be revented as many times as required.

Where reventing is impractical—such as in the case of an island sink—a “loop vent” can be provided. The loop vent (also known as a “barometric vent”) does not connect to the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.7.2025 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | RSMeans |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Technik ► Architektur |

| Schlagworte | Controllers • doors and windows • Electrical Systems • Foundation • Framing • heating and air conditioning • home building and remodeling • home energy conservations • home repair • home security • Household Appliances • HVAC • Plumbing |

| ISBN-10 | 1-394-21333-6 / 1394213336 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-394-21333-7 / 9781394213337 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich