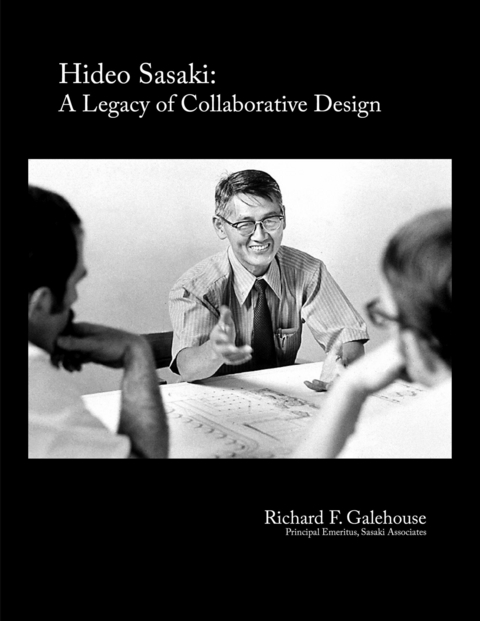

HIDEO SASAKI: A LEGACY OF COLLABORATIVE DESIGN (eBook)

108 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-9198-7 (ISBN)

David Hirzel, Sasaki principal emeritus, is a planner and urban designer who joined Sasaki in 1969 and served as principal in charge for several award-winning Sasaki projects. His professional practice has included planning and design for districts, mixed-use centers, urban waterfronts, new and historic communities, brownfields sites, military facilities, and institutional campuses.

Hideo Sasaki was one of the most consequential designers and educators of the twentieth century. His legacy lies in bringing the design professions of landscape architecture together with the other planning and design disciplines in his teaching at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the professional practice that he founded, Sasaki. The author, Richard Galehouse, first a student and later a partner of Hideo, traces the development of the Sasaki professional practice in the early decades of the 1960s and 1970s. Through selected case studies Galehouse illustrates the legacy of design collaboration that Hideo endowed to his professional practice, Sasaki, as it lives on today. In a distinguishing feature of the book, Mr. Sasaki speaks directly to the reader through excerpts from the long interview that the author carried out with Hideo Sasaki five years after Hideo's retirement. All book proceeds support the Hideo Sasaki Foundation's mission of equity in design.

INTRODUCTION

Hideo Sasaki was born in 1919 and raised on a farm in the Central Valley of California to a large Japanese-American family. In his early years he worked the family’s farm harvesting crops. The first member of his family to leave the farm and seek higher education, he began his early higher education at Reedley Junior College where he majored in general education. He moved on to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where he became interested in design and planning. Since UCLA did not have planning and design programs, he transferred to the University of California, Berkeley.

Hideo’s college career at Berkeley came to an abrupt halt at the start of World War II after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. As a Japanese American he and his family were incarcerated in Camp Poston, Arizona in 1942.

At the war’s end Hideo relocated to Chicago, Illinois. He completed his education at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, earning an undergraduate degree in landscape architecture. Following his graduation from Illinois, the Harvard Graduate School of Design awarded him a scholarship where he earned a master’s degree in landscape architecture. Upon graduation he returned to the University of Illinois and taught for two years.

While teaching at Illinois, he worked at the architectural firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) in Chicago where he became acquainted with Reginald Isaacs. Shortly thereafter, Reginald Isaacs, then recently appointed as Chair of the Planning Department at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, invited Hideo back to Harvard to teach with a joint appointment to the Departments of Urban Planning and Design and Landscape Architecture. When the school’s legal counsel determined that the terms of the grants by which the landscape architecture and planning departments were set up did not allow joint appointments, he joined the landscape architecture department. Later he assumed the role of chair of the department and remained at Harvard for seventeen years.

As Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture, Hideo brought an expansive vision to the idea of collaborative design.

I always felt that the social, environmental, and physical problems were so complex that it involved more than one discipline. I was not at any time or in any way jealous in the sense that I was personally possessive. I wanted to bring the best and it did not matter where the best came from or what profession. I think that spirit has prevailed. We do not say “well you are an architect, or you are an engineer.” That is the philosophical basis of my practice.1

In 1997 Professor Charles Harris wrote of Hideo’s impact at the Department of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design: “Under the leadership of Hideo Sasaki the decade of evolutionary change (1958 to 1968) had an almost revolutionary impact upon the nation’s major educational programs and professional offices.”2

The practice of collaborative design in 20th-century America was informed by several notable precedents of design collaboration in the 19th century.

The design of New York’s great Central Park in the mid-1850s with its precedent-setting concept of bringing nature into the dirty, congested cities of that era was the result of the collaboration of self-taught landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, architect and engineer. This great concept has been the prototype unmatched for American cities’ urban park systems. The legacy of Boston’s Emerald Necklace—Brooklyn, New York’s Prospect Park; Buffalo, New York’s Delaware Park; and other great urban parks—can be attributed to the collaboration of landscape architect, architect, and civil engineer.

The first team meeting of architects, landscape architects, civil engineers, artists, and sculptors in February 1891 in Chicago for the design of the World’s Columbian Exposition was led by Chicago architects Burnham and Root with Frederick Law Olmsted, planner and landscape architect and Abram Gottlieb, civil engineer. This team produced the “great white city” under Burnham’s famous rallying cry: “Make no little plans, for they have no magic to stir men’s blood.”3

One of the important ideas to emerge from this meeting of the design team for the World’s Columbian Exposition was the concept of urban design standards to govern the architectural design of individual buildings that are a part of a larger composition. The design team concluded, for example, that all buildings would be classical in style and set the cornice height of all buildings at sixty feet.

David F. Burg writes of the effect such a coordinated design had upon visitors:

For the first time hundreds of thousands of Americans saw a large group of buildings harmoniously and powerfully arranged in a plan of great variety, perfect balance and strong climax effect. The vision of harmonious power and beauty was such a contrast to the typical confusion of the average American town that visitors were almost stunned and the enthusiasm of their admiration bore witness to the success of the plan.4

The impact nationwide of the World’s Columbian Exposition was so powerful that it launched the City Beautiful movement in the United States. Cities throughout the United States including San Francisco, California; Chicago, Illinois; Cleveland, Ohio; and Indianapolis, Indiana launched urban design efforts that brought great parks, boulevards, and grand civic buildings to their cities.

In my interview with Hideo I asked him how these early precedents of design collaboration had come about. He noted the shared qualities of America’s early designers:

The designers of the Columbian Exposition were part of a small group of designers in the United States at the time and shared common values, ideas, and were part of one socioeconomic group. I do not believe we could accomplish a Columbian Exposition again given the diversity of views of the architectural profession. Look at the recent expositions compared to the Columbian Exposition.5

In the United States formal degrees for the design professions in higher education began in the middle of the 19th century.

In the first half of the 19th century, civil engineers were responsible for the great public works in the United States. The architectural profession evolved out of civil engineering and was formally organized under the aegis of the American Institute of Architects in 1857. Charles Eliot Norton at Harvard offered the first courses in architectural history in 1874, and Harvard established America’s first university degree program for architecture in 1895.6

Following the introduction of the architectural program in 1895, Frederick Law Olmsted, self-taught landscape architect and designer of New York City’s Central Park, and Arthur Shurcliff taught the first formal professional courses in landscape architecture at Harvard University in 1900, followed by the first degree program in 1902.7

The formal education in the planning profession began at Harvard when Professor James Sturgis Pray began planning courses within the landscape program in 1920. By 1923 Harvard offered a Master of Landscape Architecture in City Planning and established the Harvard School of City Planning in 1929. Urban design as a degree program was formally established by the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1983. Colleges and universities throughout the United States followed Harvard in offering degree programs.8

Other institutions including the American Academy in Rome and the Cranbrook School in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, also made significant contributions to the concept of the collaboration of physical designers with artists and sculptors. Charles McKim, a former student of the École des Beaux Arts in Paris and a leading designer of the “Great White City,” founded the American Academy in Rome as a “post-graduate” education for architects.9

I asked Hideo about the source of design collaboration at Harvard University.

Collaboration as such probably existed quite naturally in the olden days when the school was originally established, and the architecture school and landscape architecture school were established. If you recall the two professions were the design professions for the socially elite and the wealthy people. People who went into architecture and landscape architecture came from this same wealthy socioeconomic society. If you read the literature and you see that all of the designs were for the mansions and estates of this group.

At the American Academy in Rome, where many of them went, they had art, sculpture, architecture, and landscape architecture. Planning did not exist. When I went to Harvard and I visited some of the offices, like Nolan’s office, I went through some of the plans, like the city plan of Brookline, Massachusetts. All of them had been prepared by landscape architects. I think collaboration predates the Harvard Graduate School of Design and it grew out of that kind of tradition. When [Walter] Gropius and the Bauhaus tradition came to Harvard it was the big idea. The idea for collaboration.10

By the post-World War II era when Hideo arrived at Harvard University, the socioeconomic bonds that brought earlier generations together were long gone.

The post-World War II period in America witnessed dramatic change impacting the design professions. Thousands of veterans of World War II and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.1.2025 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | David Hirzel |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Technik ► Architektur |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-9198-7 / 9798350991987 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 35,2 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich