Power Electronics-Enabled Autonomous Power Systems (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-80350-9 (ISBN)

As the first book of its kind for power electronics-enabled autonomous power systems, it

• introduces a holistic architecture applicable to both large and small power systems, including aircraft power systems, ship power systems, microgrids, and supergrids

• provides latest research to address the unprecedented challenges faced by power systems and to enhance grid stability, reliability, security, resiliency, and sustainability

• demonstrates how future power systems achieve harmonious interaction, prevent local faults from cascading into wide-area blackouts, and operate autonomously with minimized cyber-attacks

• highlights the significance of the SYNDEM concept for power systems and beyond

Power Electronics-Enabled Autonomous Power Systems is an excellent book for researchers, engineers, and students involved in energy and power systems, electrical and control engineering, and power electronics. The SYNDEM theoretical framework chapter is also suitable for policy makers, legislators, entrepreneurs, commissioners of utility commissions, energy and environmental agency staff, utility personnel, investors, consultants, and attorneys.

QING-CHANG ZHONG, PhD, FELLOW of IEEE and IET, is the Max McGraw Endowed Chair Professor in Energy and Power Engineering and Management at Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, USA, and the Founder and CEO of Syndem LLC, Chicago, USA. He served(s) as a Distinguished Lecturer of IEEE Power and Energy Society, IEEE Control Systems Society, and IEEE Power Electronics Society, an Associate Editor of several leading journals in control and power engineering including IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, and IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, a Senior Research Fellow of Royal Academy of Engineering, U.K., the U.K. Representative to European Control Association, a Steering Committee Member of IEEE Smart Grid, and a Vice-Chair of IFAC Technical Committee on Power and Energy Systems. He delivered over 200 plenary/invited talks in over 20 countries.

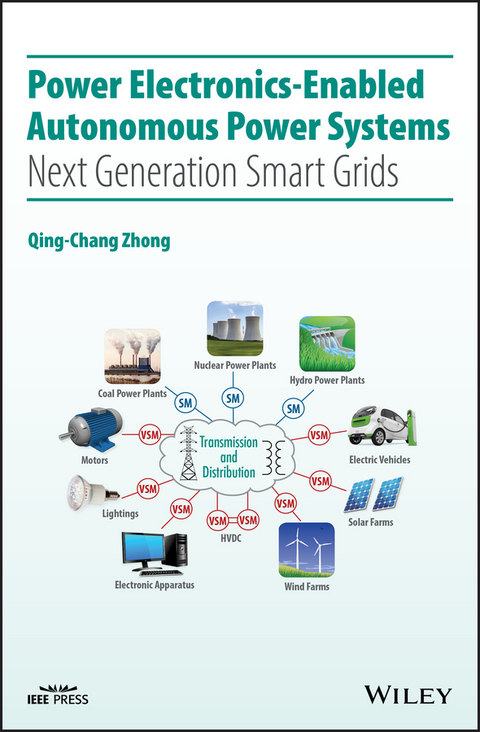

Power systems worldwide are going through a paradigm shift from centralized generation to distributed generation. This book presents the SYNDEM (i.e., synchronized and democratized) grid architecture and its technical routes to harmonize the integration of renewable energy sources, electric vehicles, storage systems, and flexible loads, with the synchronization mechanism of synchronous machines, to enable autonomous operation of power systems, and to promote energy freedom. This is a game changer for the grid. It is the sort of breakthrough like the touch screen in smart phones that helps to push an industry from one era to the next, as reported by Keith Schneider, a New York Times correspondent since 1982. This book contains an introductory chapter and additional 24 chapters in five parts: Theoretical Framework, First-Generation VSM (virtual synchronous machines), Second-Generation VSM, Third-Generation VSM, and Case Studies. Most of the chapters include experimental results. As the first book of its kind for power electronics-enabled autonomous power systems, it introduces a holistic architecture applicable to both large and small power systems, including aircraft power systems, ship power systems, microgrids, and supergrids provides latest research to address the unprecedented challenges faced by power systems and to enhance grid stability, reliability, security, resiliency, and sustainability demonstrates how future power systems achieve harmonious interaction, prevent local faults from cascading into wide-area blackouts, and operate autonomously with minimized cyber-attacks highlights the significance of the SYNDEM concept for power systems and beyond Power Electronics-Enabled Autonomous Power Systems is an excellent book for researchers, engineers, and students involved in energy and power systems, electrical and control engineering, and power electronics. The SYNDEM theoretical framework chapter is also suitable for policy makers, legislators, entrepreneurs, commissioners of utility commissions, energy and environmental agency staff, utility personnel, investors, consultants, and attorneys.

QING-CHANG ZHONG, PhD, FELLOW of IEEE and IET, is the Max McGraw Endowed Chair Professor in Energy and Power Engineering and Management at Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, USA, and the Founder and CEO of Syndem LLC, Chicago, USA. He served(s) as a Distinguished Lecturer of IEEE Power and Energy Society, IEEE Control Systems Society, and IEEE Power Electronics Society, an Associate Editor of several leading journals in control and power engineering including IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, and IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, a Senior Research Fellow of Royal Academy of Engineering, U.K., the U.K. Representative to European Control Association, a Steering Committee Member of IEEE Smart Grid, and a Vice-Chair of IFAC Technical Committee on Power and Energy Systems. He delivered over 200 plenary/invited talks in over 20 countries.

List of Figures

Figure 1.1 Structure of the book.

Figure 2.1 Examples of divisive opinions in a democratized society.

Figure 2.2 The sinusoid‐locked loop (SLL) that explains the inherent synchronization mechanism of a synchronous machine.

Figure 2.3 Estimated electricity consumption in the US.

Figure 2.4 A two‐port virtual synchronous machine (VSM).

Figure 2.5 SYNDEM grid architecture based on the synchronization mechanism of synchronous machines (Zhong 2016b, 2017e).

Figure 2.6 A SYNDEM home grid.

Figure 2.7 A SYNDEM neighborhood grid.

Figure 2.8 A SYNDEM community grid.

Figure 2.9 A SYNDEM district grid.

Figure 2.10 A SYNDEM regional grid.

Figure 2.11 The iceberg of power system challenges and solutions.

Figure 2.12 The frequency regulation capability of a VSM connected the UK public grid.

Figure 3.1 Illustrations of the imaginary operator and the ghost operator.

Figure 3.2 The system pair that consists of the original system and its ghost.

Figure 3.3 Illustration of the ghost power theory.

Figure 4.1 Structure of an idealized three‐phase round‐rotor synchronous generator with p = 1, modified from (Grainger and Stevenson 1994, figure 3.4).

Figure 4.2 The power part of a synchronverter is a basic inverter.

Figure 4.3 The electronic part of a synchronverter without control.

Figure 4.4 The electronic part of a synchronverter with the function of frequency and voltage control, and real and active power regulation.

Figure 4.5 Operation of a synchronverter under different grid frequencies (left column) and different load conditions (right column).

Figure 4.6 Experimental setup with two synchronverters.

Figure 4.7 Experimental results in the set mode: output currents with 2.25 kW real power.

Figure 4.8 Experimental results in the set mode: output currents (left column) and the THD of phase‐A current (right column) under different real powers.

Figure 4.9 Experimental results in the droop mode: primary frequency response.

Figure 4.10 Experimental results: the currents of the grid, VSG, and VSG2 under the parallel operation of VSG and VSG2 with a local resistive load.

Figure 4.11 Real power P and reactive power Q during the change in the operation mode.

Figure 4.12 Transient responses of the synchronverter.

Figure 5.1 Structure of an idealized three‐phase round‐rotor synchronous motor.

Figure 5.2 The model of a synchronous motor.

Figure 5.3 PWM rectifier treated as a virtual synchronous motor.

Figure 5.4 Directly controlling the power of a rectifier.

Figure 5.5 Controlling the DC‐bus voltage of a rectifier.

Figure 5.6 Simulation results when controlling the power.

Figure 5.7 Simulation results when controlling the DC‐bus voltage.

Figure 5.8 Experimental results when controlling the power.

Figure 5.9 Experimental results when controlling the DC‐bus voltage.

Figure 6.1 Integration of a PMSG wind turbine into the grid through back‐to‐back converters.

Figure 6.2 Controller for the RSC.

Figure 6.3 Controller for the GSC.

Figure 6.4 Dynamic response of the GSC.

Figure 6.5 Dynamic response of the RSC.

Figure 6.6 Real‐time simulation results with a grid fault appearing at t = 6 s for 0.1 s.

Figure 7.1 Conventional (DC) Ward Leonard drive system.

Figure 7.2 AC Ward Leonard drive system.

Figure 7.3 Mathematical model of a synchronous generator.

Figure 7.4 Control structure for an AC WLDS with a speed sensor.

Figure 7.5 Control structure for an AC WLDS without a speed sensor.

Figure 7.6 An experimental AC drive.

Figure 7.7 Reversal from a high speed without a load.

Figure 7.8 Reversal from a high speed with a load.

Figure 7.9 Reversal from a low speed without a load.

Figure 7.10 Reversal from a low speed with a load.

Figure 7.11 Reversal at an extremely low speed without a load.

Figure 7.12 Reversal from a high speed without a load (without a speed sensor).

Figure 7.13 Reversal from a high speed with a load (without a speed sensor).

Figure 8.1 Typical control structures for a grid‐connected inverter.

Figure 8.2 A compact controller that integrates synchronization and voltage/frequency regulation together for a grid‐connected inverter.

Figure 8.3 The per‐phase model of an SG connected to an infinite bus.

Figure 8.4 The controller for a self‐synchronized synchronverter.

Figure 8.5 Simulation results: under normal operation.

Figure 8.6 Simulation results: connection to the grid.

Figure 8.7 Comparison of the frequency responses of the self‐synchronized synchronverter (f) and the original synchronverter with a PLL (f with a PLL).

Figure 8.8 Dynamic performance when the grid frequency increased by 0.1 Hz at 15 s (left column) and returned to normal at 30 s (right column).

Figure 8.9 Simulation results under grid faults: when the frequency dropped by 1% (left column) and the voltage dropped by 50% (right column) at t = 36 s for 0.1 s.

Figure 8.10 Experimental results: when the grid frequency was lower (left column) and higher (right column) than 50 Hz.

Figure 8.11 Experimental results of the original synchronverter: when the grid frequency was lower than 50 Hz (left column) and higher than 50 Hz (right column).

Figure 8.12 Voltages around the connection time: when the grid frequency was lower (left column) and higher (right column) than 50 Hz.

Figure 9.1 Controlling the rectifier DC‐bus voltage without a dedicated synchronization unit.

Figure 9.2 Controlling the rectifier power without a dedicated synchronization unit.

Figure 9.3 Simulation results when controlling the DC bus voltage.

Figure 9.4 Grid voltage and control signal.

Figure 9.5 Grid voltage and input current.

Figure 9.6 Simulation results when controlling the real power.

Figure 9.7 Experiment results: controlling the DC‐bus voltage.

Figure 9.8 Experiment results: controlling the power.

Figure 10.1 Typical configuration of a turbine‐driven DFIG connected to the grid.

Figure 10.2 A model of an ancient Chinese south‐pointing chariot (Wikipedia 2018).

Figure 10.3 A differential gear that illustrates the mechanics of a DFIG, where the figure of the differential gear is modified from (Shetty 2013).

Figure 10.4 The electromechanical model of a DFIG connected to the grid.

Figure 10.5 Controller to operate the GSC as a GS‐VSM.

Figure 10.6 Controller to operate the RSC as a RS‐VSG.

Figure 10.7 Connection of the GS‐VSM to the grid.

Figure 10.8 Synchronization and connection of the RS‐VSG to the grid.

Figure 10.9 Operation of the DFIG‐VSG.

Figure 10.10 Experimental results of the DFIG‐VSG during synchronization process.

Figure 10.11 Experimental results during the normal operation of the DFIG‐VSG.

Figure 11.1 Three typical earthing networks in low‐voltage systems.

Figure 11.2 Generic equivalent circuit for analyzing leakage currents.

Figure 11.3 Equivalent circuit for analyzing leakage current of a grid‐tied converter with a common AC and DC ground.

Figure 11.4 A conventional half‐bridge inverter.

Figure 11.5 A transformerless PV inverter.

Figure 11.6 Controller for the neutral leg.

Figure 11.7 Controller for the inverter leg.

Figure 11.8 Real‐time simulation results of the transformerless PV inverter in Figure 11.5(a).

Figure 12.1 STATCOM connected to a power system.

Figure 12.2 A typical two‐axis control strategy for a PWM based STATCOM using a PLL.

Figure 12.3 A synchronverter based STATCOM controller.

Figure 12.4 Single‐line diagram of the power system used in the simulations.

Figure 12.5 Detailed model of the STATCOM used in the simulations.

...| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.3.2020 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | IEEE Press |

| Wiley - IEEE | Wiley - IEEE |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Technik ► Elektrotechnik / Energietechnik |

| Schlagworte | Control Systems Technology • Electrical & Electronics Engineering • electric power systems • Elektrische Energietechnik • Elektrotechnik u. Elektronik • Energie • Energy • generators • inherent synchronisation • Mechanism • Power • Principle • Regelungstechnik • Smart Grid • Synchronous • System • Systems • Underlying |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-80350-7 / 1118803507 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-80350-9 / 9781118803509 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich