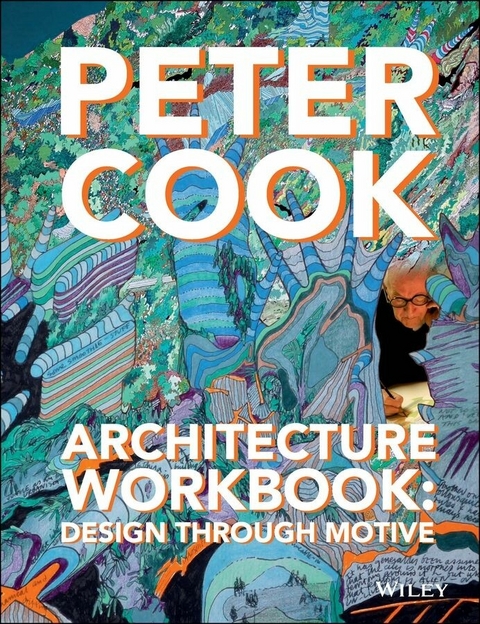

Architecture Workbook (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-96523-8 (ISBN)

Organised into 9 parts that highlight a wide range of architectural motives, such as 'Architecture as Theatre', 'Stretching the Vocabulary' and 'The City of Large and Small', the workbook provides inspiring key themes for readers to take their cue from when initiating a design. Motives cover a wide-range of work that epitomise the theme. These include historical and Modernist examples, things observed in the street, work by current innovative architects and from Cook's own rich archive, weaving together a rich and vibrant visual scrapbook of the everyday and the architectural, and past and present.

Organised into 9 parts that highlight a wide range of architectural motives, such as 'Architecture as Theatre', 'Stretching the Vocabulary' and The City of Large and Small , the workbook provides inspiring key themes for readers to take their cue from when initiating a design. Motives cover a wide-range of work that epitomise the theme. These include historical and Modernist examples, things observed in the street, work by current innovative architects and from Cook s own rich archive, weaving together a rich and vibrant visual scrapbook of the everyday and the architectural, and past and present.

Peter Cook is the founder of Archigram, the former Director of the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) in London and previous Chair of Architecture at the Bartlett School of Architecture at University College, London. A pivotal figure within the global architectural world for over half a century, in 2007 he was knighted by The Queen for his services to architecture. A Royal Academician, he is a Commandeur de l'ordre des Arts et Lettres of the French Republic. He is a Senior Fellow of the Royal College of Art, London, and Emeritus Professor at the Royal Academy, University College, London, and the Hochschule f?r Bildende K?nste (St?delschule) in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany. In 2010, he received an Honorary Doctorate of Technology from Lund University in Sweden. Cook is, with Colin Fournier, the architect of the Kunsthaus Graz. He is a director of CRAB in London with Gavin Robotham, which recently completed the new Law Faculties and Central Administration Buildings for Vienna Economics University and the Soheil Abedian School of Architecture for Bond University in Australia.

008 Motive 1: Architecture as Theatre

018 Motive 2: Stretching the Vocabulary

054 Motive 3: University Life and its Ironies

100 Motive 4: From Ordinary to Agreeable

128 Motive 5: The English Path and the English Narrative

154 Motive 6: New Places and Strange Bedfellows

186 Motive 7: Can We Learn From Silliness?

210 Motive 8: The City - Then The Town

240 Motive 9: On Drawing, Designing, Talking and Building

248 Select Bibliography

249 Index

255 PICTURE Credits

Peter Cook, Medina Circle Tower, Tel Aviv, Israel, 1997: elevation detail.

MOTIVE 2 STRETCHING THE VOCABULARY

Bruno Taut, Glass Pavilion, Deutscher Werkbund Exhibition, Cologne, Germany, 1914.

As originator of the ‘Glass Chain’ architects’ chain letter (November 1919 to December 1920) and director of the Expressionist journal Frühlicht, Taut was a visionary figure before becoming an architect of social housing projects, but here he is extending the structural and formal vocabulary and heroically grasping the potential of 20th-century glass manufacture.

Appreciating architecture can involve a practical response (‘Does it work?’ … ‘Is it helping me?’); it can have a visceral response (‘This place is creepy’ … ‘Wow! This is great!’); or it can be woven into a general feeling that architecture is a major territory that evolves and reflects the push and pull of culture in tandem with science, technology or general know-how. Along with such territories it dare not stand still. Moreover it can be observed that periods of conspicuous revivalism in architecture have mirrored stagnation, decay or even despotism in the world around it.

I feel a frustration towards the contemporary language of architecture, which often seems as if it is limiting itself by some unwritten commitment to ‘correctness’ or legitimacy of form. Even the most innovative projects seem to resort to the repetition of parts and the playing out of good manners, with a limit to the range of types of window opening, things that might happen at an entrance, ways in which a building could turn round a corner or what is an acceptable roof profile.

Architecture needs to be a constant voyage of discovery, and this is closely allied to the tricky path of inventiveness. The language by which we make enclosures – and the total scope of architectural awareness – has to question those old, comfortable manoeuvres. Ironically the bulk of new architecture, even though it is backed up by more and more efficient technical methods, is remarkably – even dangerously – repetitive and formulaic. It could be that we might soon wake up with a totally ‘standard’ architecture flanked by a tiny number of deliberately eccentric structures as court jesters against the characterless mulch.

Erik Gunnar Asplund, Law Courts extension, Gothenburg, Sweden, 1937.

A model for mannerisms to be found in European buildings up to the 1960s, Asplund knits together a lyrical set of timber-faced courts and delicate natural lighting in a combination of subtlety and boldness.

Wayward Expressionism

It has long been clear that such orthodoxy and the range of its interpretation were linked, and I increasingly became fascinated by that part of recent architectural history in which those who were hitting out against this narrowness seemed often to be labelled as ‘expressionist’. Sometimes this just seemed to be a loose term for ebullience or waywardness; yet surely there was more than a grain of truth in this word ‘expression’. It was as if these architects were not afraid to express: to celebrate, to accentuate.

The German architect Bruno Taut’s book Alpine Architecture (1917), through its associations with heroic and craggy landscape, suggested one direction of escape; and the complete originality (for its time) of his Cologne Glass Pavilion (1914) had seemed to stem from the same purposefulness of escape from the norm. This work suggested an architecture of homogeneous flow across surface and may well have underscored a desire in my mind to achieve an architecture of continuous surface, in which variations, instead of being articulated by windows and other regulated interruptions, could absorb degrees of transparency. More recently I have tended to use the phrase ‘the tyranny of the window’ as a shrill outcry against the linguistic dominance of this element, certainly in the architecture of the temperate zones: which leads one to take more seriously the relation between the later more sculptural work of Le Corbusier (1887–1965) and his travels in the Mediterranean, the liberality of Oscar Niemeyer (1907–2012) within the Brazilian climate and psychology, or the effect of the Indian subcontinent upon Louis Kahn (1901–1974). That these were probably the three most consistently influential architects upon me as a young architect could also be a factor.

Sigurd Lewerentz, St Peter’s Church, Klippan, Sweden, 1966.

A late work by the much longer-lived contemporary and sometime colleague of Asplund, who had evolved here from a Schinkel-like classicism through to a language of undulating floors, very original and dramatic positioning of light sources and surfaces of heavily cemented brickwork.

Yet as a North European, with a penchant for dampness, nuanced argument, soft evenings, only the occasional catching of bright light – but for short periods please – I sought something else than broad white surfaces and meaningful cut, sharp shadow and thick wall.

From the Transparent … to the Translucent … to the Solid … and Back Again

Irritation with the sycophancy of the window did not deter me from taking a delight in the sensuous emergence from dark to stages of grey and then, the revelation of pure vision: through glass. Increasing travels to Scandinavia and Japan have reinforced this fascination. If the Swedish architect Erik Gunnar Asplund could contrive such a mysterious series of lightfalls tumbling down within the Gothenburg Law Courts extension (1937), or his compatriot Sigurd Lewerentz could capture this precious Swedish light through small shafts that wash down the walls in his Church of St Peter in Klippan (1966), then we are involved in a quality of visual experience that the environment of harsh, regular sunshine can never enjoy.

Arata Isozaki has drawn attention to the Japanese translucency–transparency tradition by which the paper screen introduces light but not vision; only when slid open (or juxtaposed with a glazed panel) can we appreciate such vision. There is of course more to this, since the Japanese paper screen under certain conditions tantalises us by the shape of a person or object in silhouette but not detail – a trick that I found irresistible in the ‘hedonistic’ apartment for the Arcadia City project (see Motive 5).

Günter Zamp Kelp, Julius Krauss and Arno Brandlhuber, Neanderthal Museum for the Evolution of Mankind, Mettmann, Germany, 1996.

The combination of muted translucency and undulating shape serves to abstract this building from a more predictable architecture of ‘walls and windows’.

Peter Cook and David Greene, Civic Centre, Lincoln, UK, 1961.

An early competition scheme that suggests an undulating – almost amoebic – form interpreted by a continuous skin of translucent glass (later actually realised by the Neanderthal Museum), interspersed by occasional ‘eyes’ of transparency.

All of this reinforced a desire to produce a building skin that could flow continuously in the progression: solid – nearly solid – slightly translucent – more translucent – almost transparent – transparent – almost transparent – more translucent – slightly translucent – nearly solid – solid.

Most architects have been well satisfied by the character of strips of windows, in frames. More recently, there have been large glass walls where the lateral support has also been made with glass. Less usual is the creation of mystery by way of the ‘muted’ condition created with non-transparent – but translucent – glass troughs, laid vertically. This has been evocatively realised by Günter Zamp Kelp, Julius Krauss and Arno Brandlhuber in their Neanderthal Museum (1996) in the German town of Mettmann, near Düsseldorf. Moreover, in its gently flowing plan it directly recalls the competition project for Lincoln Civic Centre (1961) that I designed with David Greene, in which the meandering skin of the building was to be of those same translucent channels, but with the addition of transparent ‘bubbles’ that would appear from time to time (though rather irregularly) in the skin – in the manner of domelights used on their side.

Peter Cook and Colin Fournier, Kunsthaus, Graz, Austria, 2003: detail.

In two locations, the acrylic outer layer of the building discloses the peeling away of the inner layers – interspersed with the display of lighting rings to create a deliberately ambiguous interference with the homogeneity of the skin. Again a ‘no window’ condition that would have been repeated further if funds had allowed.

Peter Cook and Christine Hawley, house on the Via Appia, Rome, 1967.

A scheme for the ‘House at an Intersection’ competition organised by Shinkenchiku magazine demonstrates, among several other objectives, the idea of a chamber created by a skin of glass that descends from transparency (at the top) via a progressive...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.3.2016 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Technik ► Architektur |

| Schlagworte | Architectural • Architecture • Architektur • Bauentwurf • Bibliography • Building Design • City • Credits • Design • Design, Drawing & Presentation • drawing • Entwurf • Entwurf, Zeichnung u. Präsentation • Entwurf, Zeichnung u. Präsentation • Index • Ironies • Life • Motive • Motives • Ordinary • Organised • Parts • Picture • Range • Select • Theatre • Town • vocabulary • wide • Workbook |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-96523-X / 111896523X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-96523-8 / 9781118965238 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich