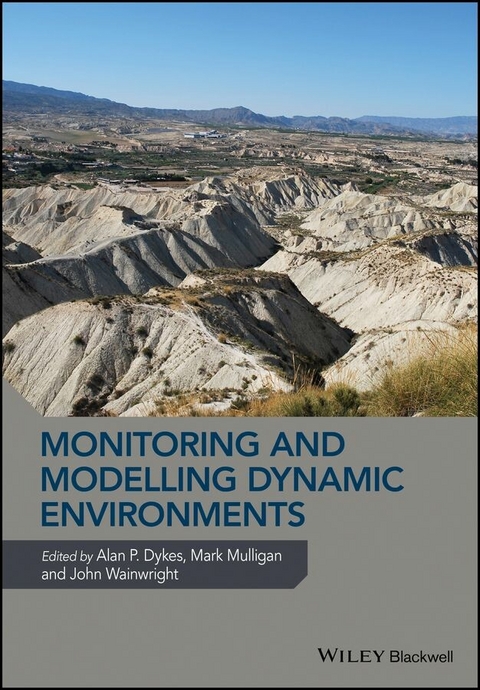

Monitoring and Modelling Dynamic Environments (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-64961-9 (ISBN)

The Times (Obituaries, 4 August 2008) reported that “John Thornes was one of the most eminent and influential physical geographers of his generation.” John’s keen interest in understanding landform processes and evolution was furthered through a variety of methods and informed across a range of disciplinary boundaries. In particular he pushed for better integration of monitoring, theoretical and simulation modelling, field and laboratory experimentation and remote sensing techniques. Although dominated by an interest in the Mediterranean region and problems of land degradation, his research activities ranged across a number of time scales and with other environmental perspectives.

This collection of papers reflects this wide range of John’s interests through the recent work of scientists and professionals most strongly influenced by his rigorous training or leadership. The thematic focus of the book, which runs through all of the main contributions, is the integration of different methodologies and the application of this approach to improved understanding of natural systems and the development of appropriate strategies for environmental and resource management. Short overviews of John’s contributions to geomorphological research are also presented to provide context for the origins of this book.

Alan Dykes undertook a PhD on tropical rainforest landforms in Brunei, supervised by Professor John Thornes, then took up his first academic post lecturing in geomorphology at Huddersfield University. Now a Senior Lecturer in Civil Engineering at Kingston University, he continues his research into all aspects of landslide science from geotechnical controls to landform evolution and specialising in peatland instability.

John Wainwright has researched questions of soil erosion, ecogeomorphology, land degradation and landform evolution across a range of space and time scales, originally inspired by the supervision of Professor John Thornes in his PhD on the erosion of prehistoric archaeological sites. He has subsequently lectured at the universities of Southampton, King’s College London, Sheffield and Strasbourg, and is now at Durham University, where he is Professor of Physical Geography.

Mark Mulligan is currently a Reader in Geography at King’s College London. Professor John Thornes supervised Mark's PhD at King's College London from 1991. Mark has remained there as a member of the academic staff since 1994 and in 2004 was awarded the Gill Memorial Award of the Royal Geographical Society–Institute of British Geographers for ‘innovative monitoring and modelling’ of environmental systems. Mark works on a variety of topics in the areas of environmental spatial policy support, ecosystem service modelling and understanding environmental change, at scales from local to global and with a particular emphasis on tropical forests in Latin America and semi-arid drylands in the Mediterranean.

Alan Dykes undertook a PhD on tropical rainforest landforms in Brunei, supervised by Professor John Thornes, then took up his first academic post lecturing in geomorphology at Huddersfield University. Now a Senior Lecturer in Civil Engineering at Kingston University, he continues his research into all aspects of landslide science from geotechnical controls to landform evolution and specialising in peatland instability. John Wainwright has researched questions of soil erosion, ecogeomorphology, land degradation and landform evolution across a range of space and time scales, originally inspired by the supervision of Professor John Thornes in his PhD on the erosion of prehistoric archaeological sites. He has subsequently lectured at the universities of Southampton, King's College London, Sheffield and Strasbourg, and is now at Durham University, where he is Professor of Physical Geography. Mark Mulligan is currently a Reader in Geography at King's College London. Professor John Thornes supervised Mark's PhD at King's College London from 1991. Mark has remained there as a member of the academic staff since 1994 and in 2004 was awarded the Gill Memorial Award of the Royal Geographical Society-Institute of British Geographers for 'innovative monitoring and modelling' of environmental systems. Mark works on a variety of topics in the areas of environmental spatial policy support, ecosystem service modelling and understanding environmental change, at scales from local to global and with a particular emphasis on tropical forests in Latin America and semi-arid drylands in the Mediterranean.

List of contributors, ix

About the editors, xi

Acknowledgements, xiii

1 Introduction - Understanding and managing landscape change through multiple lenses: The case for integrative research in an era of global change, 1

Alan P. Dykes, Mark Mulligan and John Wainwright

PART A

2 Assessment of soil erosion through different experimental methods in the Region of Murcia (South?]East Spain), 11

Asunción Romero Díaz and José Damián Ruíz Sinoga

3 Shrubland as a soil and water conservation agent in Mediterranean?]type ecosystems: The Sierra de Enguera study site contribution, 45

Artemi Cerdà, Antonio Giménez?]Morera, Antonio Jordan, Paulo Pereira, Agata Novara, Saskia Keesstra, Jorge Mataix?]Solera and José Damián Ruiz Sinoga

4 Morphological and vegetation variations in response to flow events in rambla channels of SE Spain, 61

Janet Hooke and Jenny Mant

5 Stability and instability in Mediterranean landscapes: A geoarchaeological perspective, 99

John Wainwright

6 Desertification indicator system for Mediterranean Europe: Science, stakeholders and public dissemination of research results, 121

Jane Brandt and Nichola Geeson

7 Geobrowser?]based simulation models for land degradation policy support, 139

Mark Mulligan

8 Application of strategic environmental assessment to the Rift Valley Lakes Basin master plan, 155

Carolyn F. Francis and Andrew T. Lowe

9 Modelling hydrological processes in long?]term water supply planning: Current methods and future needs, 179

Glenn Watts

10 Changing discharge contributions to the Río Grande de Tárcoles, 203

Matthew Marsik, Peter Waylen and Marvin Quesada

11 Insights on channel networks delineated from digital elevation models: The adaptive model, 225

Ashraf Afana and Gabriel del Barrio

12 From digital elevation models to 3?]D deformation fields: A semi?]automated analysis of uplifted coastal terraces on the Kamena Vourla fault, central Greece, 247

Thomas J.B. Dewez and Iain S. Stewart

13 Environmental change and landslide hazards in Mexico, 267

Alan P. Dykes and Irasema Alcántara?]Ayala

PART B

14 John Thornes and palaeohydrology, 299

Ken Gregory and Leszek Starkel

15 John Thornes: Landscape sensitivity and landform evolution, 307

Tim Burt

16 John Thornes and desertification research in Europe, 317

Mike Kirkby, Louise J. Bracken and Jane Brandt

17 John Thornes: An appreciation, 327

Denys Brunsden

Index, 331

CHAPTER 1

Introduction – Understanding and managing landscape change through multiple lenses: The case for integrative research in an era of global change

Alan P. Dykes1, Mark Mulligan2 and John Wainwright3

1 School of Civil Engineering and Construction, Kingston University, Kingston upon Thames, UK

2 Department of Geography, King’s College London, London, UK

3 Department of Geography, Durham University, Durham, UK

The twenty-first century is when everything changes. And we must be ready.

(BBC 2006)

The world is changing. It has always been changing, as internal geophysical processes drive the tectonic systems that slowly rearrange the distributions of land masses and oceans and external influences such as orbital eccentricities alter the Earth’s climate. Over hundreds of millions of years, the physical and ecological environments at any given location on land have been shaped and reshaped by natural then, from the late Pleistocene onwards, increasingly by human processes – so much so that some argue for a new geological epoch (the Anthropocene) in recognition of this (see Steffen et al. 2011; Brown et al. 2013). Our recognition of different kinds of impacts and implications of landscape changes has developed in parallel with the increasing rates of industrialisation of the last 250 years (Hooke 2000; Wilkinson 2005; Montgomery 2007). Humans are highly inventive in providing technological ‘solutions’ to feeding, watering and providing energy for ever-increasing populations, but this inventiveness does not always produce resilient or sustainable solutions. Indeed, it is often only when we are highly dependent upon these technologies that we begin to understand their negative effects on the environment that also sustains us. This is a reflection of both scientific advancement throughout the period and the increasing impacts on landscapes of the expanding industrial activities, including the industrialisation of agriculture, water and energy provision. However, although we know some of the impacts of these technologies on natural landscapes and the ‘ecosystem services’ that they provide, many aspects of the natural functioning of these landscapes remain uncertain.

The continually increasing population of the Earth has inevitably led to the expansion of anthropic modification of landscapes into increasingly marginal (in terms of primary productivity) or unstable (in terms of ecology and/or geomorphology) lands. The associated risks have driven much of the agricultural and geomorphological research that has provided the basis for the management of landscapes undergoing such changes. However, towards the late 20th century, there developed a greater awareness of the potential for long-term catastrophic losses of productive agricultural lands as a consequence of inadequate or inappropriate management (e.g. Montgomery 2007), usually stemming from inadequate relevant scientific knowledge – or the lack of communication, or application, of that knowledge in policy formulation. The early years of the 21st century have also focused attention on the potentially increasing risks of natural hazards arising from regional manifestations of anthropic, global climate change. Extreme climate events lead to floods and landslides and wind storms, all of which cause losses of life, property and livelihood, but they may also lead to more chronic adverse impacts on societies through losses of land productivity – and these effects may be exacerbated by inappropriate land management strategies and agricultural practices.

John B. Thornes recognised the importance of good basic and applied geomorphological knowledge for the sound management of landscape change relatively early. Many of his ideas were developed from his early research experiences in central Spain in the mid-1960s, although his work on the particular problems of semi-arid environments did not begin until 1972 (e.g. Thornes 1975). Fundamental to his work was the development of modelling approaches for understanding geomorphological processes and systems in parallel with the implementation of intensive field data collection methodologies to support the parameterisation of the models. Perhaps crucially, he identified the need to measure not only ‘descriptive’ parameters such as morphology or particle size – typical of early quantitative geomorphology – but also landscape properties and processes that would allow quantification of the key geomorphological issues of spatial and temporal scale and variability. As such, he was a key player in the adoption of both monitoring and modelling approaches in geomorphological research and a leader in the explicit integration of these approaches and in the application of the findings to management policy and practice. For John, geomorphology included climate, hydrology and vegetation and their interactions with geomorphological processes and thus forms and their dynamics. As well as the management of modern processes, this interaction between process and form also informed John’s understanding of past environments, particularly in his work on palaeohydrology and geoarchaeology.

Monitoring, modelling and management

Monitoring in environmental science is the process of keeping track, over time, of how one or more material properties or system states behave, based on repeated observations and measurements. It underpins the empirical understanding of environmental processes by observation of their consequences. For example, investigation of micro-scale controls on the process of soil matrix throughflow could require monitoring of water temperature (material property), soil water content and instantaneous flow velocity (static and dynamic system states, respectively). In geomorphology, many material properties are effectively constant at the timescale of a research project, but for other variables, the monitoring data required and hence the method by which they are obtained depend on the spatial and temporal scales of the problem being investigated. Technological advances over the last 30–40 years have increasingly expanded the range of what can be measured (i.e. parameter/variable type and scale) and at what frequency, although in some cases there remain constraints. For example, satellites cannot yet provide both very high temporal frequency and very high spatial resolution data – although most applications of this approach such as monitoring land-use change do not require high frequencies of repeated observations, and rapid developments in UAV techniques are addressing some of these limitations at local scales. Most field monitoring takes place at points, and the cost of equipment and labour to maintain field monitoring ‘stations’ means that there are often relatively few of these, so that significant interpolation is required for landscape-scale analysis. However, it must be remembered that remotely sensed observations are proxies of the properties or system states of interest and must be grounded in field measurement.

Modelling is the process of representing or displaying something that cannot otherwise be experienced, through abstraction of reality and representation in the form of a conceptual, mathematical or physical model. John Thornes was one of the pioneers of mathematical models in geomorphology, which are increasingly used as representations of geomorphic systems. They are usually used as a way of evaluating conceptual models of components of a system such as a specific process or a topographic subsystem representing a set of processes; furthermore, today’s office PCs can typically carry out hundreds of simulations using highly sophisticated models and produce the results before the morning coffee break. However, as with any investigation, the type and formulation of the model necessarily depends on the purpose of the research and, critically, on the quality and quantity of data that may be available to set up the model and evaluate its outputs (Mulligan and Wainwright 2004). John always understood that the geomorphological processes of greatest interest to him existed within a complex context. Over his career, through his own research and that which he supervised, collaborated with or helped to fund, he tried to ensure that as much of the relevant contextual complexity as was useful, was included. In his modelling of erosion, he started by defining and representing the process itself (Embleton and Thornes 1979). Subsequently, he introduced interactions with terrain, climate and geology (Thornes and Alcántara-Ayala 1998), then vegetation (Thornes 1990) and finally animals (Thornes 2007). All of this was done with a clear focus on the socio-economic context and the policy outcomes (Brandt and Thornes 1996; Geeson et al. 2003) and an understanding of the role of time (Thornes and Brunsden 1977) and of history (Wainwright and Thornes 2003).

The degradation of agricultural lands in the Mediterranean region has been investigated at all spatial scales, from small experimental plots on hillslopes to remote sensing of the entire region. One of the major challenges has been to integrate not only the monitoring data with the modelling of erosion processes and changing state of the landscape system but also the findings from different scales of investigation into regional-scale, operational management tools. John Thornes was quick to embrace the possibilities presented by GIS technology (particularly digital elevation models) and satellite remote sensing...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 17.7.2015 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geologie |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | earth sciences • Geomorphologie • geomorphology • geomorphology, geophysics, geology, earth science, environmental science, soil science, soil erosion, geoscience, modeling, vegetation data description, vegetation science, water resources, water conservation, simulation modeling, land degredation, hydrology, hydrological sciences, terrestrial hydrology, applied geology, coastal modeling, environmental change, climate change, climatology, paleohydrology, landscape, landform evolution, desertification • Geowissenschaften |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-64961-3 / 1118649613 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-64961-9 / 9781118649619 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich