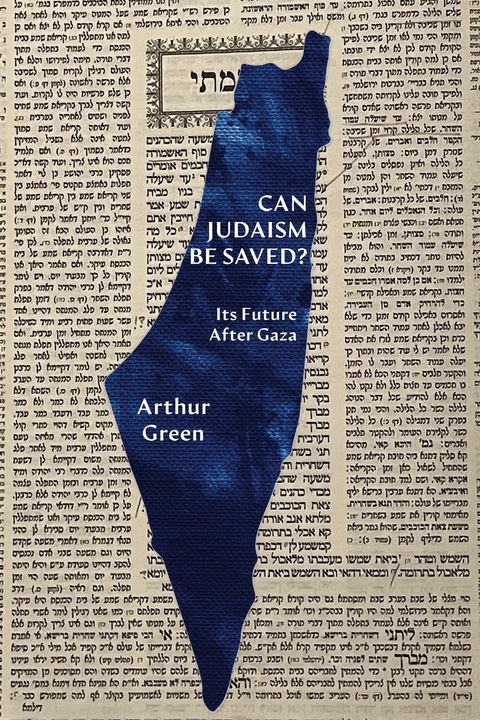

Can Judaism Be Saved? (eBook)

140 Seiten

Ben Yehuda Press (Verlag)

978-1-963475-85-2 (ISBN)

Can Judaism be saved from its most dangerous currents?

That's the question Rabbi Arthur Green poses in this urgent exploration of the spiritual and ethical challenges facing Judaism today. Green examines the tension between universalist values and exclusivist tendencies across Jewish history, showing this tension's roots in biblical, rabbinic, mystical, and Hasidic teachings.

Green challenges us to confront the darker currents within Jewish history and thought while embracing the universal truths of freedom, equality, and human dignity that lie at the heart of the Torah. He envisions a Judaism that transcends narrow nationalism and exclusivity, offering a path of service to humanity and the world.

Can Judaism Be Saved? invites readers to engage in a bold and necessary conversation about the future of Jewish identity, the role of Israel, and the moral responsibilities of the Jewish people.

'Art Green has long been one of the most significant spiritual teachers of our generation. He has now added a prophetic voice to his spiritual mission by offering a searing critique of the religious pretenses of the current Israeli government of messianists and racists, grounding his critique in Jewish texts and theology, in Jewish history and memory.'

-Dr. Michael Berenbaum, editor, A Shattered World: Jews and Israel After October 7

'At a moment when so many Jews are disillusioned with the presentation of Judaism in American Jewish life and with the political direction of the Israeli government, Arthur Green, one of our great scholars and teachers, shows us a different path: how Judaism's religious teachings can lead us to a Zionism of peace and a commitment to foster diversity and overcome exclusivity.'

-Dr. Susannah Heschel, author, The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany

Introduction

It was 1961. I was all of 20 years old, a college senior and president of student Hillel at Brandeis University. I was thrilled to be engaged in deep conversation with Rabbi Zalman Schachter, whom I had invited to spend a weekend on our campus. He was just on his way out of being a traditional Chabad Hasid, on his way to becoming the key figure of a Neo-Hasidic revival within Judaism. I had just gotten over a period of rather self-punishing Orthodoxy in my adolescent years, followed by a sharp rebellion against it. I was well on my way toward my lifelong journey as a Jewish seeker. I had met Reb Zalman earlier and I knew that he could be an important guide in finding my path. Amid many other things he said, long forgotten, he spoke one sentence that has remained with me over these more than 60 years. It was in Yiddish, a language we both understood and valued, even though most of our conversation took place in English. “Yiddishkeyt iz a derekh in avoyde,” he said. Judaism is a way of service, of serving God.

That is how I have understood Judaism over the course of all these decades. It is a path, a way of approaching a life of service to the divine, to that which is holy, to the mysterious One. Reb Zalman did not use a term for God in that sentence; it was understood. He and I would both have preferred the unpronounceable Hebrew Y-H-W-H to the English G-O-D, but we understood what we meant. Devotion, inwardness, a desire to serve, openheartedness, and “cultivation of the inner life” were all terms that characterized the spiritual path of which we were speaking, in a conversation that continued over many years. Yiddishkeyt or “Judaism” is a language in which to express that path. It is not the only such language or even necessarily the world’s best. But it is ours; it is the language our heart speaks, the spiritual legacy of our ancestors implanted within us. That is what remained—and still remains, sixty years later—important to me.

Use of the term Yiddishkeyt in this context was entirely natural for Reb Zalman, as one who had spent his formative years within a Hasidic community. But in a broader context, its use becomes more complicated. Is it to be translated “Judaism” or “Jewishness?” There once was a whole world of people out there who rejected quite thoroughly any sort of religious faith, that which they would have called “Judaism,” but affirmed precisely Yiddishkeyt as an alternative to it. The term vaguely described a set of values, including a special concern for fellow Jews and their fate as well as a certain affection for the traditional old-world Jewish way of life, without actually practicing any of its specific dictates. Yiddishkeyt was understood in those circles as something different from “Judaism.”

When I was growing up there were lots of such people. Some of them were even members of my own extended family. Today, they have retreated to a small sect of ideologically driven Yiddishists. The great majority of those who might once have belonged to that camp now just call themselves Jewish non-believers. When asked the “religion” question on a Pew survey form they check off “none.” But they still have a sense of Jewish identity, strong or weak. The vacuum created by the absence of religious faith was largely taken up by Zionism, which they see as a commitment to the Jews as a people, expressed mainly by love and support for the State of Israel.

It did not have to have happened that way. Jews have always had a strong sense of commitment to their fellow Jews, borne along and regularly reinforced by our long history of suffering. Such a sense of Jewish ethnicity or peoplehood might have sufficed to replace traditional religion for generations of nonbelievers. The problem for survival of Jewry here was that ethnicities not reflected in the color of one’s skin do not do very well in the United States. On US government census forms, which ask if you are Black, Latino, or Pacific Islander, there is no place to write “Jewish” except under “religion.” Nor is there a place to write “Italian-American” or “Polish-American.” Those forms of identity are just not considered important. We all speak English at home and root for the same sports teams. For many, regional identity within the United States becomes more important than identification with the country or countries from which one or more of one’s great-grandparents emigrated.

But for Jews, this decline in ethnic distinctiveness in America came at the worst possible time. The children and grandchildren of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe stood by and watched in horror as two thirds of the Jews remaining in Europe, one third of the entire Jewish people, were brutally and indiscriminately slaughtered. Although they mostly chose not to talk about it, every Jewish immigrant, including my own grandparents, remembered people who had been left behind and died in the pits or the gas chambers, whether they were siblings, cousins, childhood friends, or onetime neighbors. For the survivors themselves, of course, that was all much more vivid and debilitating. The plague of unspoken trauma and survivor guilt, passed from one generation to the next, did (and does) not allow most American Jews to feel comfortable with just forgetting the past and trying to fit into the New World we have been privileged to inherit.

Zionism stepped into that breach and became a surrogate religion. For a great many American Jews, support of Israel offered a link to one’s Jewish identity that could be expressed by underwriting an active Jewish life for other people, living in a land far away. One could be supportive of Jewishness for someone else, for those who chose to live in Israel. Weren’t they doing such a great job of building a new and free society, welcoming victims of anti-Jewish persecution from around the world? We should be supporting that! In this way, an American Zionist could express a loyalty to the Jewish people that did not impinge on their own full assimilation to the American Way of Life, including worship at the idolatrous Temple of “Success,” the god of the American Dream.

Of course, the lines between these forms of religious and secular self-definition are never absolute. Jews who see themselves as secular may still attend a Passover Seder and light Hanukkah candles. The message in these events, however, is often secularized. The American secular seder, if it has any meaning beyond a great family gathering and dinner, is often similar to the seder of many Israelis. It is more a celebration of the liberation from Auschwitz and the establishing of the Jewish state than it is a memory of our bondage in ancient Egypt and redemption by divine hand. If slavery is mentioned, it immediately calls for the singing of “Go Down, Moses,” better known to the participants than the traditional Hebrew songs for the occasion. Hanukkah makes it in America as a celebration of the very American value of religious liberty, even for those who reject religion. It is also, of course, a celebration of the victory of Jews over their more numerous and better armed foes, a story that immediately evokes 1948.

That replacement of Judaism, defined as a religion or a path of devotion, with Zionism, a proud feeling that Israel, especially a strong Israel, was “good for the Jews,” became the “civil religion” of the organized Jewish community. Defending Israel, no matter what it did, became the first commandment of that religion. Synagogues and rabbis, too, were expected to participate enthusiastically in this task, in addition to—and sometimes even in defiance of—whatever other religious values they might hold.

This civil religion seemed to work well for many, until 2023. Due to actions, statements, and intentions of the Israeli government, it is now in steep and rapid decline, especially for the younger generations. For them, 1945, 1948, and 1967 are nothing more than dates in history. Many within those generations, including some with strong Jewish education and commitment, have been deeply shocked and wounded, horrified by the behavior of the Israeli political leadership over the past several years. Outrage over the unfair and unequal treatment of Palestinians, which in fact has been going on for decades, was followed by a government-sponsored attempt to thwart democratic values and guarantees of an independent judiciary. It all felt too familiar to Jews living in the era of Donald Trump.

The Israeli reaction to the truly horrific massacre of October 7, 2023, made things much worse. The widespread impression, conveyed rather clearly by the Western news media, and confirmed by the vigorous Israeli protest movement, was that neither the government nor the army leadership (I do not speak here of individual soldiers, draftees who represent the full spectrum of views) care very much about the lives of Palestinians. This has been witnessed both by the massive bombing and destruction in Gaza and the cynical use and withholding of humanitarian aid as a weapon of war. Most recently, it is evidenced in the pathetic and ridiculous-sounding denial, by various Israeli spokesmen, that there is any hunger in Gaza. It’s all a “blood libel,” stemming from the world’s bitter antisemitic bias. Esau hates Jacob.

All of this needs to be said with more than a nod to the complexity of the situation. Hamas is the first villain here, not only for October 7, but for its indifference to the lives of the Gazan people ever since it came to power. It took countless millions of dollars meant to feed and clothe the needy, or...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.10.2025 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Jewish Arguments |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Judentum |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik | |

| Schlagworte | Jewish renewal • Liberal Zionism • Palestine |

| ISBN-10 | 1-963475-85-2 / 1963475852 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-963475-85-2 / 9781963475852 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich