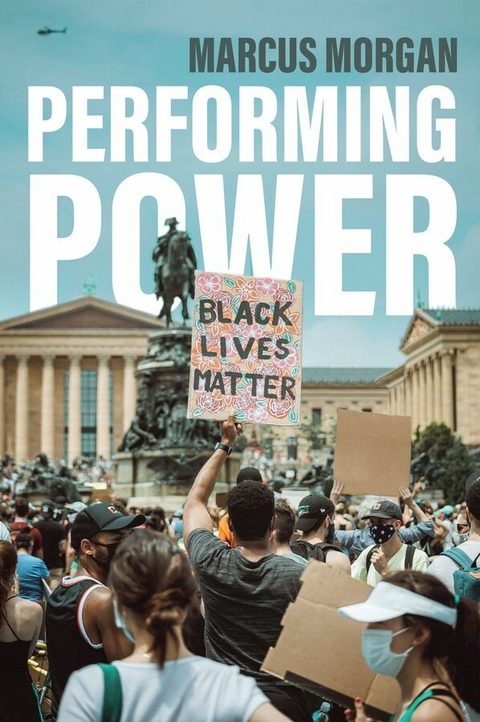

Performing Power (eBook)

378 Seiten

Polity (Verlag)

978-1-5095-5375-4 (ISBN)

The central contention of this book is that the exercise of power, and struggles for power, are inextricably linked to social performance. Political success can often be explained by the presence of engaging drama, just as political failure can be accounted for by its absence. The book explores the role of social performance in the exercise of power and evaluates the main ways in which performances of power have been understood in the social sciences, developing its own unique model for understanding them. Morgan argues persuasively that the social sciences need to take seriously the aesthetic dimensions of power, showing that in power struggles, appearance matters, and appearance is in large part achieved through performance.

Clearly written and illustrated with a wide range of contemporary examples, Performing Power will be of great value to students and scholars in political sociology, cultural sociology, and politics.

Marcus Morgan is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Bristol.

When the bronze statue of Edward Colston was thrown into the Bristol harbour, what was it about this spectacle that made it more effective than countless petitions to have the slaver s icon removed? What animated Trump s supporters to answer his rhetorical question who s going to pay for the wall? during his 2016 presidential campaign? Why do leaders of social movements, or those seeking public office, bother to appear in front of audiences when they could just as well spell out their positions in writing?The central contention of this book is that the exercise of power, and struggles for power, are inextricably linked to social performance. Political success can often be explained by the presence of engaging drama, just as political failure can be accounted for by its absence. The book explores the role of social performance in the exercise of power and evaluates the main ways in which performances of power have been understood in the social sciences, developing its own unique model for understanding them. Morgan argues persuasively that the social sciences need to take seriously the aesthetic dimensions of power, showing that in power struggles, appearance matters, and appearance is in large part achieved through performance.Clearly written and illustrated with a wide range of contemporary examples, Performing Power will be of great value to students and scholars in political sociology, cultural sociology, and politics.

1

WHAT IS SOCIAL POWER?

The concept of social power is so indispensable to understanding society (Scott, 2001) that some have described it as the ‘central concept in the social sciences’ (Haugaard and Clegg, 2009). Without it, it would be hard to explain either enduring social structure or dynamic social process: both are largely questions about how power is distributed, reproduced, and transformed. Nevertheless, and perhaps partly because of this key importance, there is deep disagreement over its basic definition. As Byung-Chul Han puts it, when ‘it comes to the concept of power, theoretical chaos still reigns’ (2019: vii).1

Lukes (2005 [1974]: 14) famously argued that much of this chaos resulted from the concept being ‘ineradicably evaluative and “essentially contested”’. Different conceptions of power arise in part from differing value commitments, which determine the kinds of empirical data that count as the presence or absence of power when different researchers study it. Conceptions of power are ‘inextricably tied to … background assumptions which are methodological and epistemological, but also moral and political’, meaning that ‘there can be disputes about the proper use of the concept of power which are both “endless” and “perfectly genuine”’ (Lukes, 1979: 678). Lukes reminds us that concepts must be understood from within their social contexts of use (Winch, 1990 [1958]), and pragmatists have pushed this idea even further, arguing that a concept’s meaning is often a residue of its utility in allowing us to do the kind of things we want to do with it (Rorty, 1979). Lukes (2022: 133) has more recently suggested that the ‘very multidimensionality’ of the power concept explains ongoing debate, and this chapter will attempt to explore some of this multidimensionality.

The word ‘power’ has its origin in the Latin potis, but arrived in English via the Anglo-French pouair, and Old French povoir, meaning ‘to be able to’ (OED). In its early meaning, therefore, it bore a remarkably close relationship to one signification of the verb ‘to perform’, the subject of the following chapter. Similarly, just as power is understood in many of its classical sociological definitions to be about one party influencing another, so too is performance defined by influential sociological theories as ‘all the activity of a given participant on a given occasion which serves to influence in any way any of the other participants’ (Goffman, 1990 [1959]: 15). However, whereas ‘power’ emphasizes the ability or capacity to do things, ‘performance’ indicates the execution or acting out of such things – ‘to carry out; to accomplish’ (OED). This distinction is reinforced in English by the fact that ‘power’, unlike ‘performance’, is less commonly deployed in its verb form in reference to social action. Nevertheless, the connection between the two words is significant and one contention of this book is that the influence flows both ways: performance enables power, as much as power enables performance, because social actors are ‘two-dimensional’ (Cohen, 1974) – both symbolic and political – and the former is often a means to the latter.

In physics, ‘power’ refers to the amount of energy transferred over a given unit of time, yet in the social sciences this notion of a transferral of energy – or power as the cause of some other effect – is only one form that power can take amongst others, and actually a rather unstable one. In fact, if one actor in a social interaction conforms to another’s wishes merely out of the transferral of energy involved in violence or some other form of coercion, many social scientists would not describe this as a genuine instance of social power at all. It was for this reason that Weber (1978: 953) distinguished between coercive power and power that resided in various types of legitimate authority. James Scott has deepened this point in relation to ‘prestige’, suggesting that to measure prestige, we might be tempted to simply observe whether one actor defers to another, yet this observation will only get us so far, since such deference may be ‘directly contradicted by general off-stage contempt’ (Scott, 1989: 146). What we observe in public deference may look very similar to authoritative power from the outside, ‘but, if we know that those complying have been threatened with a beating if they spoil the performance, we would hesitate to call this authority’ (1989: 146).

Nevertheless, not all thinkers have divorced the meaning of social power from the meaning of physical power. Bertrand Russell (1938) and Robert Dahl (1957) both proposed conceptions of social power as the cause of some other observable effect. Dahl’s position is often described as ‘pluralist’ because he understood power as spread across a plurality of social locations rather than concentrated in the hands of elites. In his contribution to the so-called ‘community power debates’, Dahl (1961a) famously suggested that if we cannot empirically observe a causal effect of power, then we also cannot, as empirical social scientists, claim that power exists. C. Wright Mills (1956, 1958) had posited an interlocking system of power across various spheres of influence, concentrated in particular amongst the political, military, and business elites who dominated American society,2 but Dahl (1958), whose arguments were based upon a political behaviourism that took seriously the notion that ‘political science’ should live up to its designation as an empirical science (Dahl, 1961b), suggested that Mills’s model could not be proven wrong. Just as philosophers of science had suggested a ‘demarcation criterion’ that separated off meaningful scientific statements from non-scientific ones on the basis of their hypothetical falsifiability (Popper, 1963), so Dahl argued that claims in political science – e.g., that a power elite ruled over American society – were meaningless if they could ‘not even in principle be controverted by empirical evidence’ (Dahl, 1958: 463). For this reason, the notion of reputed power – something that early studies adopting the ‘elite’ approach had rested upon (e.g., Hunter, 1953) – rather than actual, observable exercises of power, was condemned as prescientific. Concrete and measurable manifestations of political power, so Dahl suggested, were the only solid ground upon which a political science of social power might be established.

Whilst Dahl believed that observable behaviour granted an empirical solidity to his view of power, there is at least one important shortcoming in his approach. Using social behaviour, as opposed to what Weber called ‘social action’, as the foundation for a social science of power ignores the crucial role of meanings in social life. Weber (1978: 5) stressed that actors do not exhibit ‘merely reactive behaviour to which no subjective meaning is attached’, but rather act on the basis of what they find significant, and what they anticipate others will find significant in interaction. This becomes particularly important when we focus on performance, which by its very nature involves the projection of meanings to others. Empirically identical acts may well hold divergent meanings. Indeed, this is the aspect of social life that the hermeneutic tradition has argued separates the social from the natural sciences, and by extension therefore, the point at which the analogy of social with physical power breaks down. As Weber famously put it, ‘action is “social” insofar as its subjective meaning takes account of the behaviour of others and is thereby oriented in its course’ (1978: 5). Meaning is central to distinguishing an account of power based on mere behaviour from an account based on performance: performers consider both the meanings of their acts, and the meanings that their audiences will take from them. As will be argued in Chapter 5, such meanings need not necessarily be shared between actor and audience, let alone aim towards cooperation; they need merely be ‘oriented’, and therefore relational, to one another. This, for Weber, was the definition of any properly social relationship, be it cooperative or conflictual.

To determine the meaning of performances, and therefore move from thin descriptions of social action to what Geertz (1973), drawing upon Gilbert Ryle (1971), called thick descriptions, interpreting social action in its significant context becomes key. Only through making this move do we gain what Weber (1978: 4–12) described as ‘adequacy on the level of meaning’. Sitting on a bus seat or at a lunch counter are usually mundane and unremarkable acts, hardly performances at all; yet when these same acts were performed by Blacks in the context of racial segregation, they transformed into symbolically charged performances of power (Andrews and Biggs, 2006). With a change of social context, what was once unexceptional became extraordinary. At some later date, the meaning of this same behaviour might then be made unremarkable again, often through those earlier performances of power finding success. Meaning is therefore relationally and contextually derived, and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.10.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Allgemeine Soziologie |

| Schlagworte | aesthetics of power • Black lives matter • Colston statute • Cultural Sociology • Do politicians need to perform well in order to succeed? • edward colston • is performance important to politics? • Marcus Morgan • Marcus Morgan book • Marcus Morgan Bristol book • performance of power • performing power • Political Sociology • Politics • Power • power struggles • Sociology • why is performance important to politics? • Will politicians fail if they perform badly in front of audiences? |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-5375-4 / 1509553754 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-5375-4 / 9781509553754 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich