Strange And Interesting Traditions of Brazil (eBook)

155 Seiten

Publishdrive (Verlag)

978-0-00-095864-8 (ISBN)

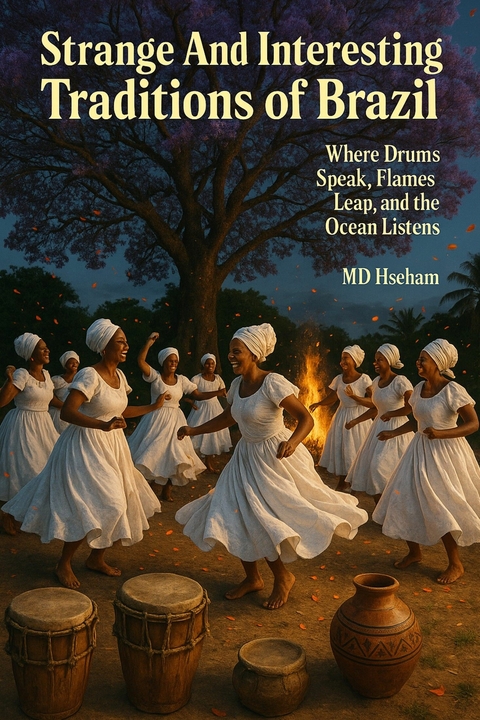

This book brings to life twenty-one of Brazil's most heartfelt and fascinating traditions-from tossing flowers into the sea for Iemanjá to washing church steps with scented water. Written in clear, simple language, it invites readers of all ages to explore the rituals that connect people through memory, music, dance, and meaning. Each chapter answers four key questions: where the tradition began, what people do, where it's practiced, and the hidden details that bring it to life. Whether it's jumping waves, spinning in samba circles, or sitting at silent dinners for the dead, these customs reveal Brazil's deep sense of community and celebration. More than cultural snapshots, these stories invite readers to reflect on their own lives, discover inspiration for meaningful rituals, and feel the universal human desire to honor time, love, and belonging. The book preserves endangered traditions, sparks curiosity, and bridges cultures through everyday magic.

1. Throwing Flowers into the Sea for Yemanjá

Brazilians celebrate New Year’s Eve with a ritual that feels both simple and profound. They gather on sandy beaches under the night sky, dressed in white from head to toe. Families, friends, and even solo travelers stand barefoot at the shoreline, clutching small bouquets of white flowers and bottles of fragrant perfume. When the clock strikes midnight, they step into the gentle embrace of the waves and toss their offerings into the sea. This act honors Yemanjá, the Afro-Brazilian goddess of the ocean, and invites her blessings for the coming year.

The roots of this ceremony stretch back to West African traditions carried across the Atlantic by enslaved people. Yoruba priests and priestesses worshipped Yemoja, a deity associated with rivers and motherhood, and they transplanted her veneration to Brazilian shores. Over time, her image merged with Catholic figures such as Our Lady of the Conception, and Candomblé terreiros (houses of worship) rose to prominence in Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, and other coastal regions. Devotees embraced the sea’s vastness as a fitting domain for Yemanjá, whose powers encompass fertility, protection, and the ebb and flow of life itself.

On December 31, samba rhythms fill the air long before midnight. Vendors hawk fresh white roses, gardenias, jasmine, and lilies at makeshift stalls lining the sand. Perfume sellers offer bottles of sweet musk or ocean-scented cologne, meant to perfume the offerings and honor the goddess’s beauty. Locals and tourists alike browse the stalls, selecting their flowers with care. Some tie small notes or personal tokens—such as lockets, photographs, or tiny trinkets—to the stems. Each guest prepares in silence or joins neighbors in chanting Yemanjá’s praise.

As dusk deepens, the beaches glow with candlelight and tiki torches—a procession often forms, led by drummers and flag-bearers representing different Candomblé nations. People carry decorated wooden boats—some small enough for a single person, others significant enough to require a handful of volunteers—to the water’s edge. They adorn these vessels with ribbons, seashells, and clusters of flowers. Even those without a boat line up to step into the shallows and launch their boats one by one. When the sea absorbs the first blossoms, the assembled crowd cheers and welcomes the New Year.

The ritual’s main feature lies in its symbolism. White represents purity, peace, and renewal. Flowers stand for life’s fragility and beauty, and perfume signifies the sweetness of good fortune. By sending these gifts to Yemanjá, participants ask her to carry away past troubles and grant health, prosperity, and emotional well-being. They believe that if the currents pull their offerings far out to sea, the goddess accepts them. When blooms come back to shore, they take it as a sign that Yemanjá has met their pleas.

Coastal towns across Brazil host variations of the ceremony. In Rio de Janeiro, Copacabana Beach attracts millions of revelers. Towering apartment blocks and luxury hotels line the sand, and fireworks burst overhead in a spectacle that rivals the ritual in scale. In Salvador, considered the cradle of Afro-Brazilian culture, locals gather at Porto da Barra Beach near the historic Pelourinho district. They dance to the rhythms of bloco drummers, offer prayers in Portuguese and Yoruba, and sometimes release floating, candlelit rafts shaped like flowers. In Recife and Olinda, smaller but equally spirited ceremonies unfold along Recife Antigo’s waterfront, fusing Yemanjá’s worship with Carnival’s upbeat rhythms.

While the tradition peaked in urban centers, smaller fishing villages maintain older practices. In communities along the coast of Espírito Santo, fishermen slip into boats at dawn on January 1, carrying baskets of flowers and bowls of water mixed with perfume. They visit offshore buoys marking sacred spots, cast offerings there, and drift in quiet contemplation. These remote ceremonies preserve the original intimacy of devotion, connecting individuals directly with the sea goddess rather than with throngs of tourists.

Interest in the ritual has grown beyond Brazil’s borders. Brazilian expatriates in the United States, Europe, and Japan organize gatherings along lakeside beaches or coastal parks. They import white flowers, sometimes drying and preserving them for the journey, and they blend local customs—such as fireworks from Fourth of July celebrations—with Yemanjá’s offerings. These diaspora celebrations reinforce cultural identity and introduce non-Brazilian guests to Afro-Brazilian heritage.

Tourists often join public ceremonies, but respectful observers study the ritual beforehand. Guides remind them to wear white, avoid plastic flowers or non-biodegradable ribbons, and refrain from wading too deeply into the water. Some terreiros consider it disrespectful for non-initiates to enter sacred waters. Organizers encourage the use of biodegradable materials to protect marine life. In recent years, local environmental groups have partnered with Candomblé communities to provide sustainable flowers, such as native white orchids grown by small farmers, and to collect floating debris after the festivities.

People of all ages participate. Children gather in family clusters, learning to tie flowers and sprinkle perfume. Teenagers stand on their parents’ shoulders to see the shoreline action. Older devotees kneel in the water—some wearing beads and cowrie-shell necklaces bestowed by priestesses—as they intone personal prayers. At midnight, the crowd breaks into spontaneous polyrhythmic chants and drum circles. Musicians play atabaque drums, agogôs, and shekerês, strengthening the bond between earthly devotees and the divine sea.

One unique feature involves writing one’s wish on a single petal before tossing it in. In Salvador, craft stalls sell small stamps that emboss petals with hearts, stars, or the letters “YEM” for Yemanjá. Devotees press petals between books to flatten and dry them as keepsakes, in case the flowers wash away. Some believe collecting returned petals can amplify future petitions. Others believe that sea turtles or dolphins—considered Yemanjá’s messengers—carry offerings deeper into her realm before returning them to shore as tokens of her favor.

Local legends tell of fishermen saved from shipwrecks after promising offerings to Yemanjá. In one story, a lone sailor drifted for days until he prayed to the goddess and spotted a pod of dolphins guiding his boat to an island. He later returned to throw an extra bouquet of gardenias into the sea, dedicating his entire next fishing season to her. Elders repeat such tales on New Year’s Eve, reminding participants that the ritual honors real spiritual power.

The tradition gained international fame through photographs in travel magazines and social-media posts tagged #Yemanja. Instagram influencers wearing white sundresses and holding giant flower bouquets share videos of waves crashing over their knees. While some criticize the commercialization of a sacred rite, many Candomblé leaders view the exposure as an opportunity to educate outsiders about Afro-Brazilian religion. Workshops on Candomblé doxology, Yoruba language lessons, and ocean-preservation drives often accompany public offerings.

Academics study the ceremony as a case of syncretism—how African deities survive under Catholic frameworks and modern tourism. Researchers document how Catholics sometimes pay homage to Yemanjá alongside Our Lady of the Conception, attending mass before heading to the beach. They note that official Catholic authorities tolerate the practice, viewing it as a popular devotion rather than heresy. In 1964, Salvador’s Archbishop officially blessed a statue of Yemanjá placed in the yard of a major Candomblé terreiro, symbolizing interfaith respect and the hybrid nature of local culture.

The ceremony’s popularity reflects Brazil’s profound connection to the sea. From pre-colonial times, coastal peoples relied on fishing and salt extraction. Portuguese colonists built ports where they could export sugar, coffee, and gold. Enslaved people labored in mangroves and on fishing boats. Those hardships nurtured a spiritual turn toward Yemanjá, who softened life’s storms. Today, fishermen still pray to her before long voyages, casting handfuls of rice and broken eggshells into the surf at dawn as small offerings.

Environmentalists sometimes voice concern that mass flower-tossing can harm marine habitats if people use non-native blooms or synthetic ribbons. In response, Candomblé groups partner with nurseries growing native white hibiscus and poinsettia, ensuring the petals dissolve naturally. They distribute eco-friendly perfume oils in refillable glass vials. After midnight, volunteers swim or snorkel out to retrieve stray pieces of plastic. These efforts demonstrate how ancient faith can adapt to modern ecological challenges.

Every year, the volume of offerings grows. In Copacabana, organizers estimate that over two million blossoms are released into the water in a single night. A volunteer crew counts petals and records their destinations with GPS buoys. Scientists analyze currents and estimate how long it takes for flowers to decompose. They use that data to map microplastics and guide cleanup missions. Meanwhile, local artists collect driftwood and seaweed stained with flowers to craft sculptures that memorialize the ceremony’s transient beauty.

For many participants, the ritual offers more than just a prayer—it provides a sense of community and a feeling of belonging. Strangers exchange smiles as they wait for the final countdown. Parents explain the ceremony to curious children, passing...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.7.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-095864-6 / 0000958646 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-095864-8 / 9780000958648 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 942 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich