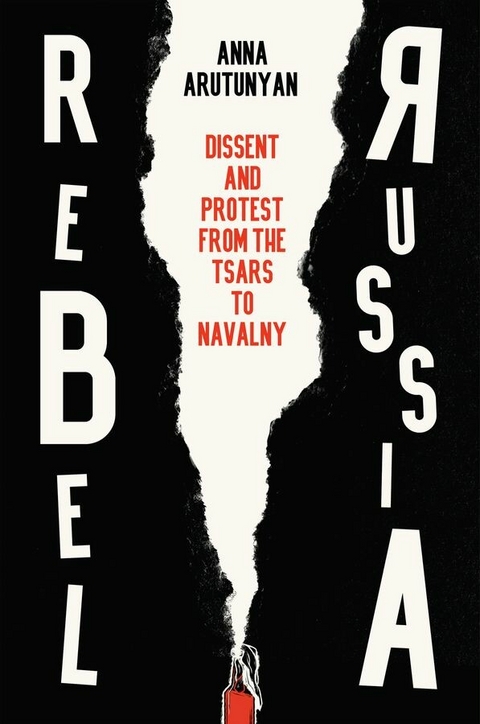

Rebel Russia (eBook)

306 Seiten

Polity (Verlag)

978-1-5095-5230-6 (ISBN)

Why do revolts - from the Decembrist uprising to the Snow Revolution that brought Alexei Navalny to the forefront of contemporary Russian politics - seem to end up failing or producing an even worse form of despotism? In reality, the brave words and deeds of dissidents have shaped the course of Russian history more often than we might think. Through the stories of prominent rebels from the time of Ivan the Terrible to the present day, as well as her own experiences reporting on her country's decent into authoritarianism, Russian-American journalist Anna Arutunyan explores how the rebel and the Tsar defined each other through a centuries-long dance of dissent and repression. These characters and their lives not only reveal the true nature of the Russian state, they also offer hope for a future Russian democracy.

Anna Arutunyan is a Russian-American journalist, analyst and author. Born in Moscow, she was raised and educated in the United States before returning to Russia where she covered two decades of Russian politics, first as reporter and editor at The Moscow News, then as an independent journalist writing for USA Today, Foreign Affairs, and other publications around the world. She served as senior Russia analyst for the International Crisis Group before leaving Russia in 2022 and is the author of five books about the country, its politics, society and its wars. She is currently a Global Fellow at the Kennan Institute and lives in England.

Navalny. Lenin. Pugachev. The Russian rebel in his epic battle against the Leviathan of the Russian state has enthralled readers and writers for decades. The rebel s story is almost always a sad one that ends in exile, imprisonment, or martyrdom, leaving but a seed for the future reform of the Leviathan which he or she had taken on. Why do revolts from the Decembrist uprising to the Snow Revolution that brought Alexei Navalny to the forefront of contemporary Russian politics seem to end up failing or producing an even worse form of despotism? In reality, the brave words and deeds of dissidents have shaped the course of Russian history more often than we might think. Through the stories of prominent rebels from the time of Ivan the Terrible to the present day, as well as her own experiences reporting on her country s decent into authoritarianism, Russian-American journalist Anna Arutunyan explores how the rebel and the Tsar defined each other through a centuries-long dance of dissent and repression. These characters and their lives not only reveal the true nature of the Russian state, they also offer hope for a future Russian democracy.

1

The Optimists

To confront Putin – and walk away

“My name is Alena Popova. Vladimir Vladimirovich, you are a colossus standing on feet of clay. We all despise you. And we want you to leave.”

It is a truism that to understand the present, you need to understand the past. In the case of Russia’s malleable history, to understand the past, sometimes you first need to understand the present.

To this day, Alena Popova, an entrepreneurial Russian politician who is now – like many independent activists – in exile, is at a loss to pinpoint what exactly made her do it. But that day in 2013, when the Russian opposition still had hope, before half of them were jailed and the other half had emigrated, before their most prominent leader, Alexei Navalny, died in an Arctic prison cell, something had accumulated in the pit of her stomach – a potent, dark nausea – and she stood there, less than a meter away, and called out Vladimir Putin to his face.

“At first, I had no desire to talk to him,” she recalls. Part of a delegation of oppositionist voices invited to Putin’s annual Valdai conference, back when the Kremlin was still trying to look vaguely democratic and inclusive, she found herself in a banquet hall following his official speech, where she and her colleagues were discussing Russia’s future. Suddenly Putin emerged into their midst. “It was just making me nauseous. I didn’t want to be a part of this. I thought, this man is absolute evil.”

Popova went instead to the bathroom. But as she tried to get out, the door was jammed. When she heaved at it, she found herself catapulted through, right into the arms of one of the president’s bodyguards. In the commotion, she somehow got thrown at the president himself.

“I turned to him, and he turned to me. I told him my name. He asked, ‘who?’ and I repeated. Then something just clicked, all these things I didn’t even know I wanted to say burst forth.” Suddenly, she knew she had to say them. “I spoke calmly and firmly. I told him that I was disgusted to stand next to him, that he was weak, that he needed to leave power, that he was so afraid of his own people that he had to find ways to prevent critics from running even for local elections.”

Putin’s spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, started pointing to his wrist, signaling to the president that it was time to leave. Peskov, a former diplomat, knew the drill and was making sure Putin had an out. To Alena, and to anyone who has observed such interactions, the subtle gesture was a tell-tale sign of the autocrat’s fragility – of a ruler afraid of his people, in spite of his efforts to seem close to them, willing to appear among crowds, chat with his subjects unscripted, and take their side against oligarchs and governors alike. It was a precarious dance that Putin had tried to maintain throughout his rule: be apparently open to spontaneity and criticism, but withdraw at the first sign of danger. This time, Putin hesitated and turned back to Popova. “Can you say that again?” he asked.

“And I told him everything again. He has to leave.”

Nearly a decade had passed when Popova told me this story. By that point, she, like so many Russians who opposed Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, had left Russia, knowing that she could go to prison simply for voicing the thoughts she held in her head. But back then, in a different Russia, nothing happened after that encounter. No arrests, no raids. Alena continued to do the work she thought necessary. “This story didn’t really mean anything. Not to him, not to me. It was a tragicomedy more than anything else.”1

When she told me about her encounter with Putin, I already had a sense of her spirit – her belief that, with her determination alone, she could effect change. She was part of a new generation of Russians – savvy enough to understand how their world worked, they also believed they were entitled to their rights and to their voice, and they were not afraid to speak out. A lawyer, journalist, and successful entrepreneur by her mid-twenties, Alena Popova became a part of a fledgling institutional democracy when she began volunteering in 2010. That summer, a massive heatwave sparked wildfires all over Russia, exposing a government that, however much it was awash with oil revenue, was catastrophically unprepared for what had been a predictable emergency. Ordinary Russians began organizing volunteer brigades to fight the fires, and Alena joined one of them, traveling to the Moscow region and as far as Siberia. Those experiences inspired her to found the Civil Corps, one of a number of volunteer groups that started cropping up at the time, focused on anything from finding missing children to helping domestic abuse victims. In 2016, she launched a network of support for domestic abuse survivors called “You Are Not Alone,” and began to lobby hard to change legislation to protect women. She would go on to set up a group that would engage lawyers to draft domestic violence legislation. Even though this was not passed, her network proceeded to help women win lawsuits against harassment. As late as 2021 – a time far more politically repressive than a decade earlier, but not quite yet the quasi-totalitarianism in which Russians would find themselves just a year later – Alena was stuffing parliamentarians’ mailboxes with pictures of abused women. By then, she had already acquired a great deal of access to the halls of Russia’s State Duma – first as an assistant to parliamentarian Ilya Ponomaryov, then as a parliamentary candidate in her own right. “When they see me coming, they turn the other way,” she told an American journalist.2

It was hard for me to imagine that, even in those relatively liberal times, knowing what she knew about the Kremlin then, she could have so brazenly told Putin to his face how much he disgusted her.

It was so hard for me to imagine, almost impossible, because I myself am not a dissident. About a year before the events she described, I too had stood in front of Vladimir Putin, less than a meter away, called out his name … and walked away.

It was 2012, and I was a reporter at Russia’s oldest English-language weekly, The Moscow News. Putin’s Russia was still relatively pluralistic and even a government-funded news outlet was free to criticize Kremlin policies. As editor of the news desk and chief political correspondent, I had been covering corruption and human rights abuses for several years. We had minimal interference from the Presidential Administration: I remember only one phone call from its offices on Staraya Ploschad, Old Square, inquiring about my reporting on a whistleblower cop who was exposing police corruption. Even the head of our news agency encouraged us to resist self-censorship. There was only one red line, really. “Criticize the Kremlin and its policies as much as you want. But attacking Putin personally is off limits.” That was the unwritten rule in those days, and I stuck to it.

But the story I had been working on when I got accredited to Putin’s yearly press conference was testing even my own impartiality. A vindictive piece of legislation had banned the adoption of Russian orphans by American foster parents. It was passed quickly by Putin’s party in direct retaliation for the US Magnitsky Law, which sanctioned Russian officials over the death in custody of jailed tax lawyer Sergei Magnitsky. Officially the authors of the so-called Dima Yakovlev Law claimed that they were defending Russian orphans, after four adoptees, including one Dima Yakovlev, had died over several years while in the care of American families. But given that thousands of children died each year from abuse or neglect at the hands of Russia’s own neglected foster care system, the only people Putin’s government was hurting were Russian orphans themselves. I had meant to confront Putin about this paradox: had he done the math, and did he know that by banning adoptions, he was sentencing thousands of Russian orphans to death?

With the press conference over, a crowd of reporters surrounded the president, and as I tried to get close, I found myself buoyed by the throng, but feeling curiously pressurized. It was as though the air within a two-meter radius of the Russian leader was charged, warping the very thoughts and words of those in the vicinity.

“Vladimir Vladimirovich!” I called out. At that moment, he was in an apparent argument with another journalist about corruption: “Look at me, I am talking to you,” he was telling her, and I clearly needed to wait. My question, formulated at the start of the conference, softened: surely I wouldn’t accuse Putin of sentencing children to death? Maybe I should actually ask if he knew that the deaths would increase by the thousands? Perhaps he didn’t. Perhaps it was my job to be useful and helpful, and point it out to him. Perhaps that way I could get him to change his mind and turn more lenient. But at the same time, as I struggled for the appropriate words, my desperation grew: a journalist’s question was transforming into a subject’s plea.

I didn’t like what was going on around me and what was going on in my head. If Alena felt nauseous, I felt ashamed. If I was going to be honest with myself, what I felt most of all was fear.

Scared, ashamed,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.5.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Vergleichende Politikwissenschaften |

| Schlagworte | Alexei Navalny • Andrei Sakharov • Boris Nemtsov • Did Putin murder Navalny? How did Navalny die? Putin • dissent • exile • freedom of speech • is Russia a totalitarian state? totalitarianism • Ivan the Terrible • Lenin • Leviathan • peter the great • Political prisoners • Prigozhin • Pugachev • Pussy Riot • Putin • Rebel • Repression • Revolt • Revolution • Russia • Russian Spring • Soviet Union • Stalin • the snow revolution • tsar • tyranny • uprising • what happened to Navalny? Ivan the Terrible • Yevgeny Prigozhin |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-5230-8 / 1509552308 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-5230-6 / 9781509552306 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich