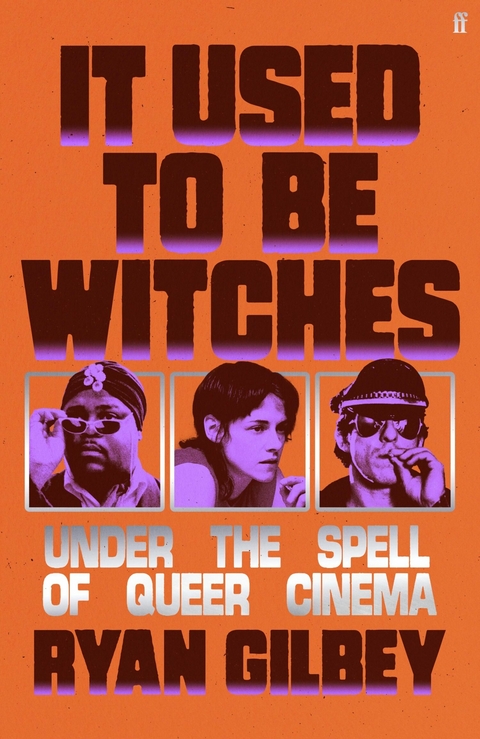

It Used to be Witches (eBook)

352 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-38154-8 (ISBN)

Ryan Gilbey has been writing on film for more than 30 years. He was named the Independent/ Sight and Sound Young Film Journalist of the Year in 1993, won a Press Gazette award for his reviews at the New Statesman, where he was film critic from 2006 until 2023, and has written for the Guardian since 2002. He is the author of It Don't Worry Me, about 1970s US cinema, and a study of Groundhog Day in the BFI Modern Classics series. He lives in London.

Playfully blending personal memoir, criticism and candid new interviews with filmmakers from across the LGBTQ+ spectrum, Ryan Gilbey's engaging and dynamic It Used to be Witches is a non-chronological treasure-hunt through queer cinema past and present. Andrew Haigh (All of Us Strangers), Cheryl Dunye (The Watermelon Woman), Isabel Sandoval (Lingua Franca) and Bruce LaBruce (No Skin Off My Ass) are among the directors who reveal how queer artists use film to express their most personal truths-and to challenge, defy and outrage a world that would rather they didn't exist. That world might look rainbow-coloured from some angles, with the likes of Brokeback Mountain, Call Me By Your Name, Moonlight and Portrait of a Lady on Fire winning awards and acclaim. But as queer and trans people find themselves increasingly under attack, It Used to Be Witches asks whether cinema can be an effective weapon of resistance and change, and celebrates an outlaw spirit which refuses to die.

It might be considered a setback when writing such a book to be told that ‘queer’ as a term is over. ‘In the US, we’re totally past that,’1 says Jessica Dunn Rovinelli in her seen-it-all tones, pushing aside the long platinum hair from her cool-kid-sister face. ‘I think it was helpful for a lot of my generation. For trans and non-binary people, it was this space in which you could play. But as brands started to market and sell the idea of queerness, it became this sort of homogenising impulse.’

We are talking over video call on a wet spring Monday, and the director of So Pretty and Empathy is doing a rotten job of breaking it to me gently that ‘queer’ is passé. ‘On the one hand, the bleeding edge of politics is done with the word “queer”, but at the same time it’s still useful to articulate to a certain group of people what that term might mean,’ she says, belatedly trying to cushion the blow. ‘Don’t forget, you’re also talking to me. A lot of other people would tell you it’s really important and that I’m a homophobe or a transphobe for not liking it.’

What’s coming next if that word has expired? What is my book about if not queer cinema? ‘Ugh, I dunno,’ she groans, her expression making it clear that this is a me-problem. ‘I am trying to care less about terminology. As I get older, I become more invested in asking: what are the material freedoms that we can afford for all genders?’ The word itself has no negative connotations for her. ‘I always found that hilarious: “We’re reclaiming it!” No one’s ever called me “queer”. They called me “faggot”.’

Rovinelli made her feature debut in 2016 with Empathy, a non-fiction film – though one, like Lizzie Borden’s Born in Flames or Juliet Bashore’s Kamikaze Hearts, that is not exactly a documentary either. The crowdfunding campaign for Empathy did deploy the D-word, however, pitching the film as ‘a performative documentary on sexual-social work’. Donors who contributed $100 received a signed postcard, a thank you in the credits and ‘a video of the director kissing any object you desire’.2

The picture follows Em Cominotti, a sex worker weaning herself off heroin; she gets a ‘story by’ co-credit, which is an early sign that any documentary component will be conditional. The camera is rarely acknowledged in Empathy, but artifice is sewn into the film’s fabric. In a nocturnal exterior shot outside a Taco Bell, an off-screen voice says: ‘Shot two, take one.’ Em waits for ‘Action!’, followed by the snap of the clapperboard’s jaws, before biting into her burrito and beginning the scene. So much for vérité.

While going cold turkey, she deals with quotidian issues: dates with clients, healthcare bureaucracy, a possible move from New York to Pittsburgh. Rovinelli prioritises largely static takes that create or dwell on contemplative spaces in Em’s life. An extended scene in a bare white room where Em is meeting a client shows the couple in bed together, the john reading Shakespeare’s sonnet 57 to her: ‘Being your slave, what should I do but tend/ Upon the hours and times of your desire?’ The ‘slave’ in this case holds all the cards and is being billed according to the hours and times of his desire. The scene also pings us back to another queer film about a hotel room assignation: The Hours and Times, which imagined what Brian Epstein and John Lennon got up to on holiday in Barcelona.

During an unshifting six-minute shot, the camera hangs back as it observes Em and her client shedding their clothes and slipping into foreplay. Rovinelli keeps the doorframe always in view on the right of the shot, so we never forget that this is an observed moment, perhaps even a staged one. She emphasises this through sound, too, blasting out Magic Fades’ euphoric, throbbing ‘Ecco’ at the beginning of the scene but not replacing the song with anything else on the soundtrack once it ends. Save for the occasional moan or whimper, the remaining two or three minutes of sex play out in a stilted, yawning silence. The whole of Empathy hangs in a series of limbo states: between addiction and sobriety, travelling and arriving, waiting and happening. Near the end of the film, we hear the voice on Em’s meditation tape telling her: ‘In any circumstance, you can start afresh. You have the power and control to start a new moment at any time.’ Quite the queer concept.

The tensions in Empathy between life and its cinematic facsimile are amplified in Rovinelli’s 2019 follow-up, So Pretty, adapted from Ronald M. Schernikau’s novel So Schön. The film’s form keeps shifting, just as the relationships – between a group of queer friends and lovers in a Brooklyn commune – morph within it. There are moments in which the characters read from Schernikau, seeming to will into existence the adaptation we are watching, while commenting on their own relationship to the text or their resemblance to the book’s characters.

Interludes show them standing at a microphone in a field, reading from what appears to be a script. ‘This film tells of four young people attempting to organise their love,’ announces Erika (Rachika Samarth). Theatricality is foregrounded, only for documentary realism to intrude repeatedly in the shape of footage of real New York City demonstrations and protests, or intimate scenes of conversation or sex, or the creeping spectre of an inevitable break-up. The naturalism in the performances collides with casual acknowledgements of artifice: ‘This is a flashback,’ says one actor; ‘This is a flash-forward,’ says another. In this way, So Pretty is not merely a film that knows it’s a film, but a text making the transition to the screen, writhing and wriggling in front of our eyes. Rovinelli captures a state of flux that is political, social, sexual and artistic. The process of the movie discovering what it is becomes the movie itself.

I won’t be the last person to describe So Pretty as Brechtian. What Rovinelli has tired of hearing, though, is the word ‘gaze’, which has become the Japanese knotweed of film theory. ‘I don’t want to talk about the “gaze” ever again in my life,’ she says. ‘It’s like: “O-kay, the female gaze!” These floppy generic terms don’t help us make better cinema or understand women or men or trans people.’ Isn’t So Pretty a film of many gazes? ‘Yes. One of which hopefully belongs to the audience.’

Her own responses to films as a younger viewer were initially visceral. ‘Crying is what attracted me to the movies as a child. I would go see them largely with male friends – most of the little teenage cinephile circles I was in were young boys – and it was very beautiful that we would chase this act of sobbing together.’

Consequently, she pays close attention to how her own teenage fans online respond to So Pretty. But in an age of fluidity, she resists the idea of the film as a manifesto. ‘I have a certain frustration with So Pretty because it does represent, I think, a milieu of utopian queerness – and I do worry that it can participate in the same universalising nothingness that I spoke about earlier. But the film has a lot of young fans, and most of them seem able to recognise the fantasy elements. The film says, “We live like this. You can live like this!” And nobody lives like this. In reality, the quote–unquote “trans community” is filled with incredible cruelty, as any minority group that is isolated from larger spaces is going to be. Any woman who has existed as a trans woman will discover: “My God, these people do not have my back.” So this is how it could be, but it’s not how it is.’

It’s an awareness that only occurred to her subsequently. ‘I started making So Pretty as a man. It was aspirational. I knew it was fantasy. It was an attempt to make a film that’s set in a world I might want to live in, which is what Schernikau was doing in the original text.’ Where is her head at now? ‘The phase I’m in is anti-representational. I want to continue working with a diverse group of people in front of and behind the camera as a labour issue, because I think these labour politics are incredibly important, but the idea that representation can save us is, I hope, dying. Representation is not fucking working. And I don’t want to make films to present us as good subjects. I’d rather present us as vile subjects. Because if we can only exist as the best version of ourselves, we will die.’

If representational politics has a political thrust in the real world, she says, it is one of provoking actual violence against the very people it’s supposed to help. ‘It creates the image of some who are deserving of participation, of inclusion, of material benefits, and some who are not. The...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 3.6.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Film / TV |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Kommunikation / Medien ► Journalistik | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-38154-5 / 0571381545 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-38154-8 / 9780571381548 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich