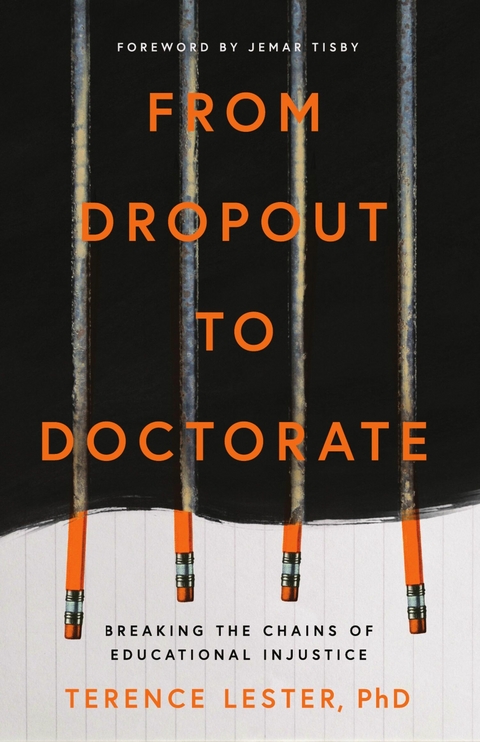

Terence Lester (PhD, Union Institute and University) is a storyteller, public scholar, speaker, community activist, and author. He is the founder and executive director of Love Beyond Walls, a nonprofit organization focused on raising awareness about poverty, homelessness, and on community mobilization. He also serves as the director of public policy and social change and as a professor at Simmons College of Kentucky (HBCU). He is the author of I See You, When We Stand, and All God's Children, and he coauthored with his daughter, Zion, the children's book, Zion Learns to See. He and his family live in Atlanta.

Terence Lester (PhD, Union Institute and University) is a storyteller, public scholar, speaker, community activist, and author. He is the founder and executive director of Love Beyond Walls, a nonprofit organization focused on raising awareness about poverty, homelessness, and on community mobilization. He also serves as the director of public policy and social change and as a professor at Simmons College of Kentucky (HBCU). He is the author of I See You, When We Stand, and All God's Children, and he coauthored with his daughter, Zion, the children's book, Zion Learns to See. He and his family live in Atlanta.

INTRODUCTION

WHEN ROSES GROW FROM CONCRETE

Growing up in the early nineties, I listened to a lot of music. As I navigated childhood poverty and the impact of a home that ended in parental separation, music and poetry helped me cope with the pain, giving me a language I couldn’t always articulate on my own.

One of my favorite artists was Tupac Shakur. Pac was complicated; his words could both inspire and upset you. I related to the side of him that was deep-thinking, reflective, and provided a critical analysis of the struggle of Black people. Songs like “Dear Mamma,” “Keep Ya Head Up,” “Brenda’s Got a Baby,” and “To Live & Die in LA” were deeply reflective of the Black struggle for survival during the late eighties and early nineties.

Knowing that Tupac wrote not just hip-hop but other forms of poetry gave me a chance to connect with him and add meaning to my reality. In 1999, MTV Books released Tupac’s book of poetry, The Rose That Grew from Concrete, with poems that he had handwritten from 1989 to 1991.1 The poems were discovered after his death. They talk about his struggle, the realities of the streets, the lack of support for impoverished communities, and his pain, fears, and hopes. The beginning of the poem that gives the book its title is loaded with depth and meaning, asking, had the reader heard of the rose that had grown “from a crack in the concrete?”

The poem is a metaphor that speaks to the beauty contained within people who have to navigate the harsh realities of poverty. Yet it also reveals the systemic concrete-like layers that make it even harder for that beauty to grow. His words could even paint a powerful metaphor of a child who, by their impoverished circumstances, experiences more trauma even than some adults, yet still tries to do their best. That child may live in a food desert, suffer verbal or physical abuse by a family member, have to take care of their siblings while their one parent or guardian goes to work, have to deal with poverty and urban hassles, or have to choose between buying food and washing their clothes in the coin laundry.2 The concrete may be their own body: sex-trafficked, exploited, experiencing homelessness, living in a motel room with five or more family members. It may be their mind: struggling with depression or exhaustion, too distracted and encumbered by pain to connect with schoolwork. It may be the foster care system: the state of having no family strong enough to care for them or no family at all. Whatever the story, some young person is that rose, trying to overcome the injustices created by the hard exterior of their environment.

I know. I was one of those roses.

I grew up in poverty on Campbellton Road in the city of Atlanta. As a teenager, I joined a street gang. I dropped out of school, and I experienced moments of homelessness—after choosing to leave home—and hopelessness. Many times, I didn’t think I would make it.

In my mind, I can still see the unfinished roads because the local government wouldn’t be quick to make repairs. The vacant lots. The Black businesses, holding on by a thread called community. The liquor stores and pawn shops, deep symbols of neglect and disinvestment, not to mention the school buildings that were never renovated when I was a child, leaving students with outdated textbooks and inadequate facilities. I can still hear the sounds of sirens and feel the fear of getting caught in the crossfire, which became part of daily life because of the hostile nature of trying to survive.

These circumstances and environments can lead to deep trauma in the life of a young person, young adult, or any adult trying to survive. Poverty, inadequate housing, a lack of guidance, and hopelessness all contribute to a deep sense of feeling stuck with the burden of nihilism. This type of environment requires immense resilience, grit, and a set of survival tactics that become second nature to any young person trying to navigate it all.

Even as a child, I had a deep understanding and intuition that education could give me the space to dream, escape, and imagine myself in places beyond my social context. But my environment had a more significant impact on my educational path than I would have wanted. Imagine journeying through such experiences while trying to produce good grades and maintain enough courage to get to school, sit in a classroom, and do schoolwork. The trauma from being raised in poverty makes it challenging to focus on learning when survival is the primary concern, let alone listen to a teacher teach about things that have nothing to do with your reality or existential experiences.

However, I want to preface my work in this book by saying that poverty does not mean less community, less brilliance, less courage or collective strength. In fact, many who navigate poverty exhibit extraordinary resilience, creativity, and solidarity in ways that often go unrecognized.

In another poem, “Government Assistance or My Soul,” Tupac challenges the stereotypes that often stigmatize those faced with poverty and unemployment.3 He makes it clear that not everyone who needs assistance from the government because they are poor is brought to that point because of personal failings; rather, they have been met with systemic conditions that contribute to their lack and suffering. Tupac’s powerful poetic words shed light on both the physical and emotional toll it takes daily to survive and grow under harsh conditions. The words in the poem communicate how poverty attacks one’s sense of self, altering how one sees the world and others.

I know this firsthand because I had my own struggles growing up in a single-parent home, seeing my mother work multiple jobs to take care of my sister and me. The trauma from family breakdown and poverty caused abuse, unhealthy communication, neglect, and other harmful traumas in my own life and the life of my family. My own encounters with trauma and poverty have given me a deeper understanding of the havoc they wreak on communities and lives, creating all types of emotional challenges that become nearly impossible to escape without proper support. It is a fact and reality that this happens more to Black children and children of color who are trying to find a way out of environments that have historical and systemic injustices tied to them.

The interplay of poverty and racial injustice introduces an additional layer of complexity to the struggle of someone navigating all this, often placing them at a significant disadvantage when it comes to educational achievement. It creates the type of barriers that uphold what I would call educational injustice. When I say educational injustice, I am talking about systemic barriers and inequities that disproportionately hinder Black children and children of color from historically marginalized communities, making it harder for them to flourish in school (K-12) and blocking their path to quality education and higher learning. These barriers make it harder for them to succeed and thrive like their peers who do not have to deal with systemic and social ills. Children raised with trauma and in poverty start from behind, long after the race has begun, and must navigate through fraught social and emotional landscapes. This burden is deeply rooted in a broader historical and systemic context that demands more understanding as we look at why access to higher education (that is, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and PhD programs) is harder for children of color, particularly children who are Black.

Poverty, trauma, and their effects can be long lasting for any child or adult trying to overcome them and can set a person up for failure—whether in getting a job, navigating a healthy family life, or pursuing academic achievement. Even if a person never plans to seek higher education, it is still important to feel safe enough to pursue whatever they want—to have equity meet them. That so many people never feel that kind of safety is due to systemic barriers, meticulously constructed over generations, that create what some scholars identify as transgenerational or multigenerational trauma: a phenomenon I discuss in depth in chapter two and give real life examples of throughout the book.4

I define systemic barriers as a set of hindrances, embedded obstacles, social challenges, and designed limitations that are socially constructed to hold back, oppress, or marginalize a vulnerable group of people from the resources and opportunities that might give them access to upward mobility. Consider the jelly-beans-in-a-jar test that hindered Black people from the political process and voting. Targeted policing and racial profiling. Vagrancy laws. Unequal education and health care. Or any number of other barriers that disadvantage a group of people. What drives these barriers are public policies that establish false social norms, mostly put in place by the people who hold power and can decide who those public policies will aid or disadvantage. These decisions structurally marginalize communities, placing a lid on potential for educational, social, and economic growth.

However, what we do not often talk about is how systemic barriers are deeply connected to trauma—and how this trauma itself can travel through generations, becoming emotional and social roadblocks. According to the mental health treatment facility A Place of HOPE, experiencing trauma as a child leaves lasting mental and emotional scars that extend beyond childhood, affecting people into adulthood. These experiences can make it hard to see the path...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.9.2025 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Jemar Tisby |

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Schulbuch / Wörterbuch |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik ► Erwachsenenbildung | |

| Schlagworte | ACCESS • African American • BIPOC • Black • children • Diversity • Divorce • Domestic violence • Equity • Gang • higher education • Homeless • incarcerated • Inclusion • jail • Juvenile Delinquent • Kids • Minority • Poverty • School system • School-to-prison pipeline • Trauma • unhoused |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-1149-2 / 1514011492 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-1149-2 / 9781514011492 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich