Courage to Lead with Integrity for Equity (eBook)

212 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-9082-9 (ISBN)

Dr. Ronald G. Taylor, a Morehouse College graduate ('95) and George Washington University doctorate holder, has over 28 years of public education leadership, including 13 as Superintendent. He pioneered the Intentional Integration Initiative, presented to the NJ Legislature, and taught as an adjunct professor at Rowan University. A champion of equity and innovation, Dr. Taylor now advises educational entities post-retirement while serving with Hazard Young Attea & Associates and Equal Opportunity Schools.

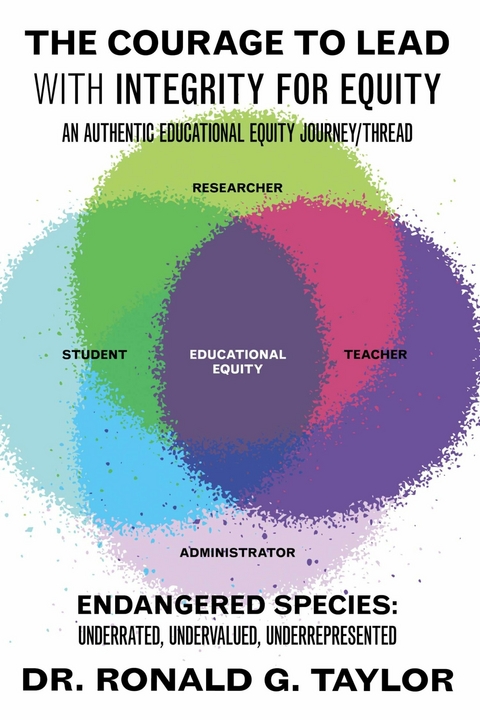

Dr. Taylor's book examines the enduring influence of 'school equity' on his educational journey, beginning as a student and evolving through roles as a teacher, principal, superintendent, and researcher. He recounts how educational equity initiatives repeatedly shaped his life and inspired him to implement impactful measures that improved outcomes for thousands of students. Dr. Taylor delves into his scholarly research, including his notable 2009 dissertation, featured by the Education Facilities Clearinghouse (EFC), on the connection between school facility conditions and student achievement. This research laid the groundwork for his legacy as a superintendent, where he oversaw school construction projects exceeding $200M across multiple districts. The book weaves together Dr. Taylor's personal experiences, professional milestones, and academic contributions to offer a compelling narrative of leadership, integrity, and the pursuit of equity in education.

My obsession with the topic of school equity began at the age of twelve. This timeline is still so clear to me because it was the first real shift I recall from my childhood. I grew up in Detroit, Michigan, in a working-class neighborhood. Some would have called it lower-middle class, or even the ghetto. Like many in my community, my father was not a presence in my life, but I was so fortunate to have a loving, hard-working mother and grandmother who cared deeply about my education. It was well known by my family members that my father was an addict who had abused my mother. My father had been abusive to my mother even in front of my family members. My mother never spoke ill of my father and only answered questions that I asked during that time in her life. My father briefly returned to my life at the age of eleven. I was so used to him not being around that when my friends would ask me who the man was who had stopped by during that year or so, I would tell them he was my crazy cousin or uncle, shamed by his appearance and surprised by his arrival. One of my only early memories of my father was him kidnapping me from a school play. I was excited and prepared to participate (I was around six or seven years old), and I recall him picking me up from the play and taking me to an older lady—whom I did not know—and leaving me there. Confused and scared, I only recall bits and pieces, but the fear was palpable. Years after that trauma, he came to visit me once in a while in an awkward effort to either relieve himself of guilt or add meaning to his life. I was never proud to have him as a father and was more fearful than respectful. After leaving Detroit at the age of twelve, I only saw him once in my life. I would have dreams (more like nightmares) in my adolescence after moving to Atlanta that he found my mom and me. In my early twenties, I returned to Detroit to see my sister, who stayed in the city and was eight years older than me. She had, by this time, started her own family. She asked if I wanted to see my dad, and I begrudgingly agreed. We went to the neighborhood that he lived in and asked around the local store. My father’s nickname was “Radio” because everyone knew him for working at the first Black radio station in Detroit (at least that is the story I was told). As we went to a few stores in the vicinity (we did not have his address.), asking where to find him, more than one person told me that I looked like him. That was the first time I had heard that from anyone outside my family. When we found him, I was in a bit of shock. This man, who I viewed as terrifying for the majority of my life and who I feared would find me, was small. Really small. Much smaller than me. He had suffered a stroke, and half his body was limp and paralyzed. My sister joked with him about how big I was. We sat in the dimly lit small room that he lived in and had small talk. He asked about my mom, and then he told me that he wanted to see me, but my aunts would not tell him where I lived. The banter brought a weird closure for me. A closure that I didn’t know I needed. We exchanged telephone numbers, but neither of us called, and a few years later, my sister told me that she heard he had died. To this moment, that news did not give me sadness or despair. My sister said, “You know he loved you,” and I honestly did not feel that authentically.

My mother named me after my father’s brother, who died before I was born, even though she wanted to make me a junior. My father insisted on honoring his sibling. The compromise was that I would take his first name, Gerald, as my middle name. As I grew up, my mom always insisted that I put my middle initial in my name because my uncle Ronald Taylor could have had a son in Detroit and that could cause identity confusion. To this day, I still include the initial G in my name, and every once in a while, I get asked what it stands for. Weirdly, it gives me unexplainable pride to say, “It’s my dad’s name”. While authoring this book, I recently had the revelation that I do not have a family picture with my father, mother, and me. Nor do I have a picture of my father and me. I don’t share this for sympathy or pity, but just a reality that sometimes, our trauma is so close to our daily reality, we don’t realize the ‘lack of normalcy’ that it can represent.

Mom and Radio

From age two until twelve, I attended the neighborhood Catholic school named “Epiphany”. My family’s major reason for sending me to this school was the proximity (directly across the street) and the early-age daycare for a toddler, which would allow my mom and grandmother to continue to work full-time and provide our essentials. Even though we did not have a car and had to depend on walking or rely on public transportation (even in the harshest of Michigan winters), I never recall feeling poor or ‘less than.’ I recall my mother and grandmother sharing stories, reflecting on their time growing up in rural Georgia, picking cotton as their main job. They would say that they were happy during that time and did not realize how poor they were. They spoke about how fresh the home-cooked food was and how they slaughtered chickens, etc. This interested me so much that later I asked my mom, “You all did not know you were poor, huh?” She said, “You don’t realize you are poor now.” That struck me because I never thought I was poor. Even in this book, I described my neighborhood as working class, etc. While I never really remember missing anything that we needed, I also understood that there were some things that my family could not afford, and I would not burden them by even asking.

When I think back on my experiences at Epiphany, I recall the feeling of being a Big Man on Campus (BMOC). I felt like I had always gone there. It was the only school I had known since I was two years old. While it was a small Catholic school. I do not recall any memorable focus on religion, even though the principal was a nun. I recall it as just being a happy time, with extracurricular opportunities that included sports and theater performances. We wore homemade costumes and athletic uniforms. We drew our numbers on our T-shirts for games. I also recall the school being small, not in physical facility size but in the number of students, classes, etc. There were not more than a few classes per grade level from preschool to the eighth grade.

In 1985, my mother was laid off from her job and my grandmother was close to retirement as a nurse’s aide, so my family made the decision to relocate to Atlanta, Georgia. My mother’s had four (4) siblings there, and the city was known to have many job opportunities as well as a blossoming progressive African American population. When we arrived in Atlanta, I attended South West Middle School. This school’s enrollment was of more than 1000 students, close to 100 percent African American students, and a staff that closely mirrored the demographics of the student body. My former school, Epiphany, had roughly a quarter of this enrollment. Although my new school was a public school, I believe the population of South West had a significantly higher socio-economic status per capita than Epiphany. The students at South West wore designer clothes and shoes, while my former school required a simple uniform, white shirts, and blue pants. While it took me a while to acclimate, I made friends and, eventually, adjusted to my new school and surroundings.

This transition was my first encounter with feelings and thoughts that are now connected to school equity, in retrospect. Before this transition, I never gave serious conscious thought to the brands of clothes I wore or even the types of shoes. I recall having school clothes, play clothes, and church clothes. I recall getting new ‘gym shoes’ twice a year in Detroit. I do not recall comparing myself to my peers concerning our families’ financial standing. One could surmise that this is simply the result of becoming an adolescent. I assert that this was not the case for me. I had such high self-esteem, as I mentioned earlier. The palpable feeling of being a BMOC shifting to the feeling of being less than par was connected to the difference, not only in my (1) school location and the understood anxiety of (2) restarting as an outsider (for the first time in my life), but there also was a significant connection to my (3) socio-economic status compared to a population that many would otherwise see as my demographic peers.

Some would ask: How is this experience from my childhood an example of school equity? Both schools had all Black students. Beyond the clear previous reference to socio-economic student (equity) differences and the mental health connections that can spawn from this, i.e., bullying, self-harm, acting out, etc. When challenging students’ transitions are not recognized, anticipated, and planned for by educators, it can lead to even more concerning behaviors. I do not recall speaking to a school counselor ever or having an orientation for new students, etc.—things that are commonplace now to assist with new school transition. An example of a concerning behavior that I recall clearly and specifically is dumbing down my responses to teachers. Not answering questions for fear of standing out. Many children who move to new areas of the country can ‘code-switch.’ While many academics define code-switching in their research to be based on second-language learners mixing their native language with the language that they are learning (Zhou and Wei, 2007), for purposes of this discussion, it is pertaining to the different enunciations of different regions of the United States. Children who move between regions can begin to imitate...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.1.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-9082-9 / 9798350990829 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 10,5 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich