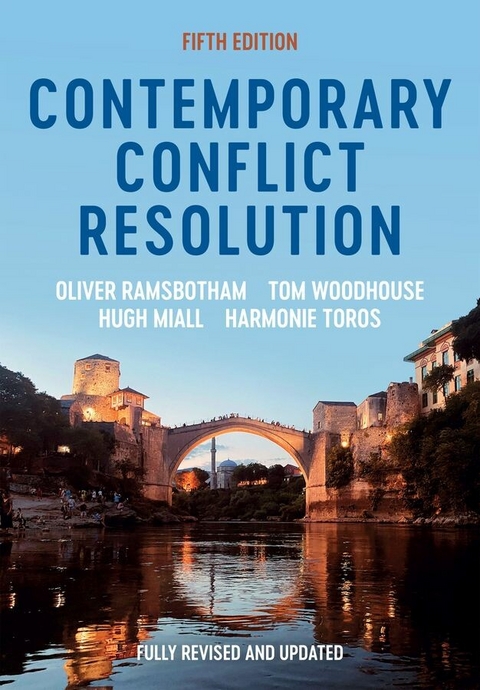

Contemporary Conflict Resolution (eBook)

993 Seiten

Polity (Verlag)

978-1-5095-5760-8 (ISBN)

The indispensable guide to conflict resolution in a troubled world

Conflict prevention and resolution, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding have never been more important as priorities on the global agenda. The wars in Ukraine and Gaza, and tensions between the major powers in what is now a multi-polar world, require new conflict resolution responses. The fifth edition of this hugely popular text offers a commanding overview of today's changing conflict landscape and the latest developments and new ideas in the field. Fluently written in an easy-to-follow style, it guides readers carefully through the key concepts, issues and debates, evaluates successes and failures, and assesses the main challenges for conflict resolution today.

Comprehensively updated and illustrated with new case studies, the fifth edition returns to its favoured twelve-chapter format. It remains the leading text for students of peace and security studies, conflict management and international politics, as well as policy-makers and those working in NGOs and think tanks.

Oliver Ramsbotham is Emeritus Professor of Conflict Resolution at the University of Bradford.

Tom Woodhouse is Adam Curle Emeritus Professor of Conflict Resolution at the University of Bradford.

Hugh Miall is Emeritus Professor of International Relations at the University of Kent.

Harmonie Toros is Professor of Politics and International Relations at the University of Reading.

The indispensable guide to conflict resolution in a troubled world Conflict prevention and resolution, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding have never been more important as priorities on the global agenda. The wars in Ukraine and Gaza, and tensions between the major powers in what is now a multi-polar world, require new conflict resolution responses. The fifth edition of this hugely popular text offers a commanding overview of today s changing conflict landscape and the latest developments and new ideas in the field. Fluently written in an easy-to-follow style, it guides readers carefully through the key concepts, issues and debates, evaluates successes and failures, and assesses the main challenges for conflict resolution today. Comprehensively updated and illustrated with new case studies, the fifth edition returns to its favoured twelve-chapter format. It remains the leading text for students of peace and security studies, conflict management and international politics, as well as policy-makers and those working in NGOs and think tanks.

Introduction

As a defined field of study, conflict resolution started in the 1950s and 1960s. This was at the height of the Cold War, when the development of nuclear weapons and the conflict between the superpowers seemed to threaten human survival. A group of pioneers from different disciplines saw the value of studying conflict as a general phenomenon, with similar properties whether it occurs in international relations, domestic politics, industrial relations, communities or families, or between individuals. They saw the potential of applying approaches that were evolving in industrial relations and community mediation settings to conflicts in general, including civil and international conflicts. Chapter 1 gives an account of how the new field developed over the next fifty years to the point where, when the Cold War came to an abrupt end in the 1990s, many government ministries and international regional and global organizations were using the language and some of the concepts pioneered by conflict resolution in the expectation – or hope – that the Cold War could be succeeded by an era in which the original aspirations of the founders of the United Nations in 1945 might at last be realized.

The aim of the Introduction is to prepare the ground for our survey of contemporary conflict resolution today by looking briefly at what happened over the next thirty years or so since then – 1991 to 2024 – which roughly coincides with the publication of the five editions of this book. Certainly, the skies have darkened over the intervening period. As we write, the war in Ukraine continues, and the growing rivalry between China and the US adds to fears that old disputes over territorial status could trigger a new Cold War or something worse. In January 2023 the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists set the hands of its doomsday clock to ninety seconds to midnight, declaring humanity the closest it has come to the threat of destruction. In March 2023 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a warning that this decade, up to 2030, would be the last chance for humanity to avoid irreversible environmental damage. On 7 October 2023 the attack by Hamas on Israel marked a new intensity in the unresolved Israeli–Palestinian conflict. At the same time social media are driving polarization and fragmentation, even in previously stable democracies, and new technologies are making existing conflicts more dangerous.

Are the challenges from contemporary conflicts so severe that they threaten to overwhelm the prospects for conflict resolution? Or do the statistics still suggest that the long-term trend overall is towards the possibility in the future of a more peaceful world in which the field of conflict resolution can rise to these new challenges?

Conflict Resolution and the Arrow of History, 1991–2024

To set the scene we have chosen a seminal book by Kalevi Holsti published in 1991 to frame this discussion. Holsti analyses successive attempts to create a peaceful post-war international order over the period 1648 to 1945 and looks at the main conditions that determine success or failure. We can then consider the years 1991 to 2024 against this background.

Looking at these epoch-making phases of war and peacemaking at great power level – after the Thirty Years’ War (Westphalia 1648), Louis XIV’s wars (Utrecht 1713), the Napoleonic wars (Vienna 1815), the First World War (Paris 1919) and the Second World War (San Francisco 1945) – Holsti identifies what he calls eight ‘prerequisites for peace’:

- governance (some system of responsibility for regulating behaviour in terms of the conditions of the agreement)

- legitimacy (a new order following war cannot be based on perceived injustice or repression, and principles of justice have to be embodied into the postwar settlement)

- assimilation (linked to legitimacy: the gains of living within the system are greater than the potential advantages of seeking to destroy it)

- a deterrent system (victors should create a coalition strong enough to deter defection, by force if necessary, to protect settlement norms, or to change them by peaceful means)

- conflict resolution procedures and institutions (the system of governance should include provision and capacity for identifying, monitoring, managing and resolving major conflict between members of the system, and the norms of the system would include willingness to use such institutions)

- consensus on war (a recognition that war is the fundamental problem, acknowledgement of the need to develop and foster strong norms against use of force and clear guiding principles for legitimate use of force)

- procedures for peaceful change (the need to review and adapt when agreements no longer relate to the reality of particular situations: peace agreements need to have built-in mechanisms for review and adaptation)

- anticipation of future issues (peacemakers need to incorporate some ability to anticipate what may constitute conflict causes in the future: institutions and system norms should include provision for identifying, monitoring and handling not just the problems that created the last conflict but future conflicts as well).

Table 0.1 The evolution of attempts to create a peaceful postwar international order

* short-lived governance mechanism in League of Nations

** failure to develop deterrent capacity such as proposed Military Staff Committee or UN Standing Forces

Source: Holsti (1991: ch. 13)

Holsti recognizes that the requirement to ‘enlarge the shadow of the future’ as specified in the last two prerequisites is highly demanding:

It may be asking too much for wartime leaders to cast their minds more to the future. The immediate war settlements are difficult enough. But insofar as the peacemakers were involved not just in settling a past war but also constructing the foundations of a new international order, foresight is mandatory. The peace system must not only resolve the old issues that gave rise to previous wars; it must anticipate new issues, new actors, and new problems and it must design institutions, norms, and procedures that are appropriate to them. (Holsti, 1991: 347)

From his vantage point in 1991, Holsti concluded that the more criteria that were met in each agreement the more stable and peaceful was the ensuing period. The San Francisco meeting that established the United Nations in October 1945 in his view did a great deal to stabilize interstate relations and provides one explanation at least for the subsequent decline of interstate war.

The disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991 – the year Holsti’s book was published – and the abrupt ending of the Cold War were seen by some at the time as an opportunity for agreement on a further expansion of the ‘postwar international order’ beyond the 1945 settlement. If so, how does the more than thirty years that have elapsed since then measure up to Holsti’s prerequisites for peace? If the post-1991 international order is seen to represent the interests and values of the victors in the Cold War, Holsti’s seventh and eighth ‘prerequisites for peace’ are complicated when the settlement is threatened by shifts of relative power among them. In 1945 the defeated powers – Germany, Italy, Japan – had surrendered unconditionally, were occupied, and were then integrated into the subsequent new postwar order by more powerful states. This did not happen in 1991. In 1991 the defeated power – the Soviet Union – had not surrendered, or even lost a battle, and was not occupied. But it ceased to exist and disintegrated into its constituent fifteen Soviet Socialist Republics – one of which, the Russian Federation, remained a great power. The subsequent Ukraine conflict was an aftershock of that seismic geopolitical earthquake. And all of this coincided with the economic rise of China, a decisive internal shift of power within that country, and its subsequent political (and military) challenge to US global hegemony. Conflict resolution has had to adapt accordingly – as it did in the years after 1945 in response to the sudden advent of the bipolar Cold War marked by the Soviet acquisition of nuclear weapons (1949), the communist victory in China (1949), and the Korean War (1950–3).

Successive Editions of Contemporary Conflict Resolution Compared

Let us now compare successive editions of Contemporary Conflict Resolution with changing conditions at the time they were written over the 1991–2024 period. In each case we thought that the revision would involve little more than an update of policies, data and literature. Each time it required a fundamental rethink – such has been the pace of change. Above all, the bipolar Cold War period subsequently moved with remarkable rapidity through a unipolar moment, dominated by what some called the US ‘hyperpower’, to the current revival of great power rivalry and the emergence of a new multipolar world that is replacing it. The conflict resolution response has had to adapt accordingly.

The unipolar period of US dominance

At the time of the first edition of Contemporary Conflict Resolution in 1999, despite the catastrophes in the middle of the decade in Somalia, Rwanda and former Yugoslavia, international support for conflict resolution still seemed to be strong, with the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Vergleichende Politikwissenschaften |

| Schlagworte | Adam Curle • bestselling textbook on war and conflict • Conflict Resolution • Contemporary Conflict Resolution • Harmonie Toros • Houthi rebels in the Red sea • Hugh Miall • International Law • International Relations • military history books • Oliver Ramsbotham • Peace operations • Russia and Ukraine war • Russian politics • russo-ukrainian war • Tom Woodhouse • transnational conflict • Transnational crime • War in Gaza • War in Ukraine • wars in the Middle East • what is genocide |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-5760-1 / 1509557601 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-5760-8 / 9781509557608 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich