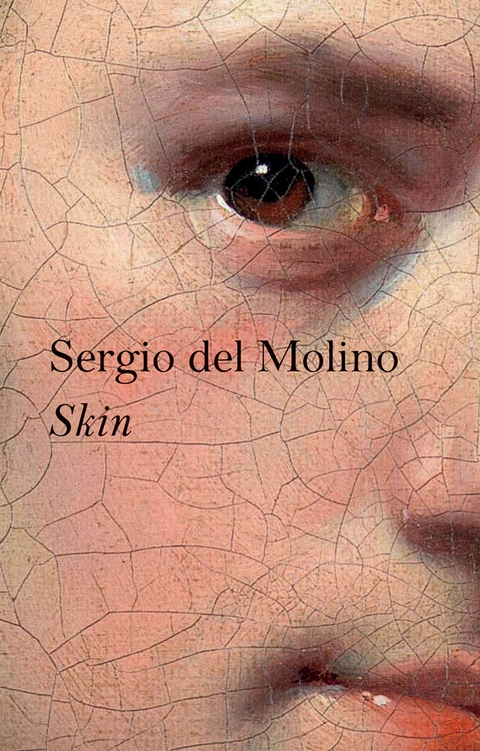

Skin is the border of our body and, as such, it is that through which we relate to others but also what separates us from them. Through skin, we speak: when we display it, when we tan it, when we tattoo it, or when we mute it by covering it with clothes. Skin exhibits social relationships, displays power and the effects of power, explains many things about who we are, how others perceive us and how we exist in the world. And when it gets sick, it turns us into monsters.

In Skin, Sergio del Molino speaks of these monsters in history and literature, whose lives have been tormented by bad skin: Stalin secretly taking a bath in his dacha, Pablo Escobar getting up late and shutting himself in the shower, Cyndi Lauper performing a commercial for a medicine promising relief from skin disease, John Updike sunburned in the Caribbean, Nabokov writing to his wife from exile, 'Everything would be fine, if it weren't for the damned skin.' As a psoriasis sufferer, Sergio del Molino includes himself in this gallery of monsters through whose stories he delves into the mysteries of skin. What is for some a badge of pride and for others a source of anguish and shame, skin speaks of us and for us when we don't speak with words.

Sergio del Molino is one of Spain's leading writers of fiction and nonfiction. His numerous books include La España vacía, La hora violeta and Lo que a nadie le importa.

Skin is the border of our body and, as such, it is that through which we relate to others but also what separates us from them. Through skin, we speak: when we display it, when we tan it, when we tattoo it, or when we mute it by covering it with clothes. Skin exhibits social relationships, displays power and the effects of power, explains many things about who we are, how others perceive us and how we exist in the world. And when it gets sick, it turns us into monsters. In Skin, Sergio del Molino speaks of these monsters in history and literature, whose lives have been tormented by bad skin: Stalin secretly taking a bath in his dacha, Pablo Escobar getting up late and shutting himself in the shower, Cyndi Lauper performing a commercial for a medicine promising relief from skin disease, John Updike sunburned in the Caribbean, Nabokov writing to his wife from exile, Everything would be fine, if it weren t for the damned skin. As a psoriasis sufferer, Sergio del Molino includes himself in this gallery of monsters through whose stories he delves into the mysteries of skin. What is for some a badge of pride and for others a source of anguish and shame, skin speaks of us and for us when we don t speak with words.

Sergio del Molino is one of Spain's leading writers of fiction and nonfiction. His numerous books include La España vacía, La hora violeta and Lo que a nadie le importa.

Gratitudes and Debts

Witches Don't Egg-sist

The Devil Card

A Swimming Pool in Sochi

The Magic Mountain

The Prettiest Girl in Sandy Ground

A Very Brief History of Racism

The Middle Ages of The Skin

When the Working Day is Done

Conversations With a Stone King

The Boss's Comb

My Greek

Impure

Butterfly in Basque

Habit

'Cogent and insightful'

The Guardian

'Deeply moving... Del Molino writes with a soft touch, and his political, literary and cultural world is richly resonant throughout.'

The Spectator

'Compelling... While he sometimes wishes he were invisible, del Molino bares his own skin in this reflective, sometimes digressive, beautifully written book.'

The Sydney Morning Herald

'Sergio del Molino's beautifully written account of skin and its complications is the starting point for a profound reflection on human imperfection and how we deal with it. Drawing on personal experience, while always striving for social and political meaning, it ranks among the best books I've ever read.'

Andreas Hess, University College Dublin

'When you pick up this book you must realise one thing: The book is written so masterfully that you won't read it, rather you will scratch, pick and obsess your way through it. Skin is memorable because you live every character and experience in it through your body's own reactions of discomfort, self-consciousness and transient relief.'

Nina Jablonski, Pennsylvania State University

'A beautifully written book. It is as raw, lyrical and paradoxical as our most human organ. Sergio del Molino has a rare skill in using our outer surface to express the richness of the human condition.'

Monty Lyman, University of Oxford

'Brave, naked, touching. A work of stark and ravishing lucidity. Epic.'

Irene Vallejo, author of Infinity in a Reed

'An elegantly written work informed by history, psychology, philosophy and sociology, Sergio del Molino's book is in the main a humane, sensitive and insightful study of the disorders to which our human skin is prey.'

Society

The Devil Card

When the metamorphosis was just beginning, and the rash nothing but tiny blotches that could just as well have been fleabites, I was living with a witch in Madrid. It was early autumn in 2000, I was 21 years old and, though I’d had dealings with witches before, it was the first time I’d lived with one. She was the friend of a friend. Our friend in common found out that she had an unoccupied bedroom in her flat in Cuatro Caminos and wanted a flatmate to split the costs. What luck, said my friend: I’ve got a friend who’s looking for a room. And she got us together.

I was studying journalism, which is to say I only ever went to university when it was time for an exam, which I would have revised for the previous night using the photocopied notes some very diligent girl had taken down in her convent-school handwriting. The rest of the time I spent in other departments (Philosophy, for example, reading French novels from the library) or in the National Film Library, unsystematically guzzling down the work of all the classic directors. The witch was in the same department as me, but studying PR and advertising, and attended classes daily, sometimes taking immaculately clear notes in convent-school handwriting. We were enrolled in the same building, but various worlds separated us. I had chosen indigence and indolence; she dreamed of offices in glass towers, cocaine and prize ceremonies at Cannes; for me it was the bar life, the low life, smoking the occasional joint (though I never inhaled) and letting my hair grow long.

In the world of PR execs she was aiming for, if she wanted to fit in she would need to tone down the witchy personality, but only to an extent. Getting rid of the nastiest aspects – like the unsightly eczema and the blue saliva – was enough. Otherwise, a touch of the esoteric always goes down well in high society. It needs framing in an elegant, Ibiza-dwelling sort of way, like the kind of attire – just something I threw on – that only looks good on the rich and tanned. A witch can be a good publicist, so long as she avoids getting sucked into some Getafe dive where she’s obliged to wear a turban and read the coffee grounds for slot-machine-addicted housewives convinced (always correctly) that their husbands are cheating on them with the woman, or women, next door. Patricia, which was my witch’s name, was learning to modulate her esoteric register in order to be able to fit in at a summer party in Marbella, which was why she warned me against any indulgence in the mass-market side of witchcraft. For example, she forbade me from going into La Milagrosa, the santería shop below our flat, where they sold black candles in the shape of gigantic penises, which I used to find hilarious.

Don’t play around with that, she would say. Promise me you won’t buy anything from that place, they’re bad people, and they do black magic. I’m warning you.

And that magic was black, but as in the colour of its skin. What really bothered her about La Milagrosa was that its client base came from the Caribbean and from illiteracy, and a hip publicist wasn’t going to win a contract with Coca Cola if she showed up singing African mumbo jumbo with voodoo beads around her neck. Her magic always had to be the refined, white, European kind. Or Asian at best, and India trumped China. Racism is rife among people involved in esoteric practices, and I found it infuriating, because I really wanted one of those gigantic penises but, out of respect for my racist witch, I never bought one.

Patricia had a beautiful set of tarot cards, which only she was allowed to touch – it will de-magnetise, she said, you mustn’t contaminate it with your energy – and which had been designed by a White Russian in goodness knows which decade and which country. That was why the devil card had Stalin’s face. When I was home alone, I defied her prohibition, opened the drawer containing the cards, took them out of the pouch she kept them in, and shuffled and ran my fingers over them. It was a brightly coloured set, Russian art-like, with pictures that resembled byzantine icons, all fierce eyes and unflinching looks. I greatly enjoyed handling them, and it was a real let-down that Patricia never noticed I had been doing so. She never registered my having de-magnetised or contaminated them with my energy.

Read my cards, would you, Patricia? I said in a moment when I felt my faith growing weak and wished to renew my vows.

Patricia was lazing around. She was perfectly happy watching the television and had no desire to clear the coffee table in the living room, which was forever covered in glasses and bottles.

Come on, Patri, come on my girl. Read my cards.

Puffing out her cheeks, she grudgingly lifted herself off the sofa, turned the TV off and got the cards out of the drawer.

You tidy up this shithole for me, she said. You’ll get a terrible reading with all these dirty glasses around.

She shuffled, and told me to cut the pack without touching the backs of the cards, only the sides. She then set about lining them up in rows, laying one at a time as though this was solitaire, and murmuring to herself the while. With her, it was never a case of good or bad cards: Patricia said all of that meant nothing, the cards were neither good nor bad, nor did they predict the future. They were a projection of your personality. She always played down the magical aspect, reducing everything to a question of natural energies and biochemistry. It was not the magic objects that had power over us, but the other way around: our bodies – casings for the spirit – left imprints that she was able to read, bringing her into an understanding, in a few short minutes, of the person across from her, the kind of understanding that those of us who aren’t witches take years of intimacy, cohabitation and nocturnal conversations to achieve. The cards were a diagnosis of the present, never a future prediction.

And an indulgent diagnosis, obviously. Patricia portrayed me in a way that I would like. Or in a way she thought I would like: you’re impulsive, you have a real inner strength; don’t overlook your rational side, seeing how sentimental you tend to be, which is necessary in the right moment, but can also be debilitating for you. Plus, wow, I see a very charged sexual energy. If you run into someone else bursting with it like you are, it’s going to be a hell of a meeting. But make sure they don’t dominate you.

Easy, Patri, I think I can dominate myself. You’re not going to have to put a bolt on your door tonight.

Idiot. Shall I carry on?

Carry on, carry on, please.

And she went on laying cards, until Stalin came out.

The devil!, I shrieked. Oh no.

I’ve told you a thousand times, the devil isn’t bad. And particularly in your case.

How can it not be bad, it’s Stalin! Look at that scowl, that moustache! He’s very bad. Don’t sugarcoat it for me, I can take whatever it is. Tell me what it means.

There isn’t one single meaning. This isn’t a science, it’s perception, art, interpretation. Within this spread, it’s alerting you to your instincts, it’s saying they might betray you. Look, I’ve drawn it upside down.

That’s bad.

The cards next to it tell us it’s to do with health. Have you noticed anything strange recently? Any pain, anything bothering you?

Nothing at all.

And those blotches on your arm?

Just a rash.

It’s been there for quite a few days.

Does the devil upside-down mean ill health?

It’s a way of warning you that something’s incubating, some danger for the body, almost always sexual. You haven’t had unprotected sex, have you?

Oh, bugger Stalin.

I only offer warnings. You men are so carefree – plus you in particular go to bed with every madwoman around. So, I don’t believe you for a second.

I’m telling you, no. Neither protected nor unprotected. I’ve been spending my every waking minute at the National Film Library these last few weeks. I could have picked something up there. They say there are fleas.

If you bring fleas into the flat, I’ll throw you down the stairs. And keep an eye on those blotches, they don’t look like a normal rash to me. Do they itch?

A bit.

You mustn’t scratch them.

I won’t scratch, Comrade Stalin.

You’re doing it right now.

I’m a dissident, that’s the thing.

And an imbecile. Now, leave me be for a bit, I’m going to meditate in my room. I’ve got a statistics exam tomorrow. You, get yourself a doctor’s appointment.

She shut herself in with her supermarket candles (never from La Milagrosa) and the bag of bog-standard sea salt with which she made a protective circle on the ground, and I didn’t see her again until the following day. I never bothered her when she entered that state, not so much out of respect as because those rituals struck me as a piece of overacting that jeopardised her metamorphosis into a cosmopolitan, liberal kind of witch. It pained me to see her plunge into an esotericism so down-at-heel.

I went on scratching those nanoscopic blotches – the colour of which varied from red to light pink according to the light, the time of day or how hydrated or dry my skin was – until they bled. Then I saw that...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.9.2021 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Thomas Bunstead |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Mikrosoziologie | |

| Schlagworte | Anthropologie • Anthropology • Comparative & World Literature • Literature • Literaturwissenschaft • skin, witch, psoriasis, monster, social, health, dermatitis, epidermis, mask, illness, age, youth, Cyndi Lauper, Vladimir Nabakov, Stalin, humanity, gaze, watch, identity, self-perception, beauty, cosmetics, decoration, affliction, pariah, racism, prejudice, colourism, image, medicine, sense, touch, discomfort, privilege, power • Social & Cultural Anthropology • Sociology • Soziale u. kulturelle Anthropologie • Soziologie • Vergleichende Literaturwissenschaft u. Weltliteratur |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-4787-8 / 1509547878 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-4787-6 / 9781509547876 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich