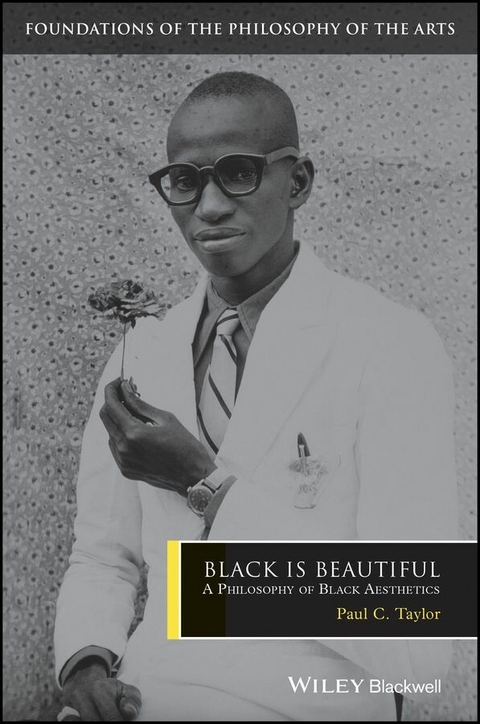

Black is Beautiful (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-32869-9 (ISBN)

- The first extended philosophical treatment of an important subject that has been almost entirely neglected by philosophical aesthetics and philosophy of art

- Takes an important step in assembling black aesthetics as an object of philosophical study

- Unites two areas of scholarship for the first time - philosophical aesthetics and black cultural theory, dissolving the dilemma of either studying philosophy, or studying black expressive culture

- Brings a wide range of fields into conversation with one another- from visual culture studies and art history to analytic philosophy to musicology - producing mutually illuminating approaches that challenge some of the basic suppositions of each

- Well-balanced, up-to-date, and beautifully written as well as inventive and insightful

- Winner of The American Society of Aesthetics Outstanding Monograph Prize 2017

Paul C. Taylor teaches Philosophy and African American studies at the Pennsylvania State University, where he has also served as Head of the Department of African American studies. Professor Taylor has provided commentary on race and politics for newspapers and radio shows on four continents. He is the author of Race: A Philosophical Introduction (Polity, 2003; 2nd ed. 2013), has recently completed On Obama (Routledge, 2015), and is one of the editors of the Routledge Companion to the Philosophy of Race (forthcoming).

Black is Beautiful identifies and explores the most significant philosophical issues that emerge from the aesthetic dimensions of black life, providing a long-overdue synthesis and the first extended philosophical treatment of this crucial subject. The first extended philosophical treatment of an important subject that has been almost entirely neglected by philosophical aesthetics and philosophy of art Takes an important step in assembling black aesthetics as an object of philosophical study Unites two areas of scholarship for the first time philosophical aesthetics and black cultural theory, dissolving the dilemma of either studying philosophy, or studying black expressive culture Brings a wide range of fields into conversation with one another from visual culture studies and art history to analytic philosophy to musicology producing mutually illuminating approaches that challenge some of the basic suppositions of each Well-balanced, up-to-date, and beautifully written as well as inventive and insightful Winner of The American Society of Aesthetics Outstanding Monograph Prize 2017

Paul C. Taylor teaches Philosophy and African American studies at the Pennsylvania State University, where he has also served as Head of the Department of African American studies. Professor Taylor has provided commentary on race and politics for newspapers and radio shows on four continents. He is the author of Race: A Philosophical Introduction (Polity, 2003; 2nd ed. 2013), has recently completed On Obama (Routledge, 2015), and is one of the editors of the Routledge Companion to the Philosophy of Race (forthcoming).

Preface and Acknowledgments vii

1 Assembly, Not Birth 1

1 Introduction 1

2 Inquiry and Assembly 3

3 On Blackness 6

4 On the Black Aesthetic Tradition 12

5 Black Aesthetics as/and Philosophy 19

6 Conclusion 26

2 No Negroes in Connecticut: Seers, Seen 32

1 Introduction 33

2 Setting the Stage: Blacking Up Zoe 35

3 Theorizing the (In)visible 36

4 Theorizing Visuality 43

5 Two Varieties of Black Invisibility: Presence and Personhood 48

6 From Persons to Characters: A Detour 51

7 Two More Varieties of Black Invisibility: Perspectives and Plurality 58

8 Unseeing Nina Simone 63

9 Conclusion: Phronesis and Power 69

3 Beauty to Set the World Right: The Politics of Black Aesthetics 77

1 Introduction 77

2 Blackness and the Political 80

3 Politics and Aesthetics 83

4 The Politics-Aesthetics Nexus in Black; or, "The Black Nation: A Garvey Production" 85

5 Autonomy and Separatism 87

6 Propaganda, Truth, and Art 88

7 What is Life but Life? Reading Du Bois 91

8 Apostles of Truth and Right 94

9 On "Propaganda" 98

10 Conclusion 99

4 Dark Lovely Yet And; Or, How To Love Black Bodies While Hating Black People 104

1 Introduction 105

2 Circumscribing the Topic: Definitions and Distinctions 107

3 Circumscribing the Topic, cont'd: Context and Scope 109

4 The Cases 110

5 Reading the Cases 115

6 Conclusion 129

5 Roots and Routes: Disarming Authenticity 132

1 Introduction 132

2 An Easy Case: The Germans in Yorubaland 134

3 A Harder Case: Kente Capers 136

4 Varieties of Authenticity 138

5 From Exegesis to Ethics 144

6 The Kente Case, Revisited 151

6 Make It Funky; Or, Music's Cognitive Travels and the Despotism of Rhythm 155

1 Introduction 156

2 Beyond the How-Possible: Kivy's Questions 157

3 Stimulus, Culture, Race 159

4 Preliminaries: Rhythm, Brains, and Race Music 162

5 The Flaw in the Funk 168

6 (Soul) Power to the People 172

7 Funky White Boys and Honorary Soul Sisters 174

8 Conclusion 177

7 Conclusion: "It Sucks That I Robbed You"; Or, Ambivalence, Appropriation, Joy, Pain 182

Index 186

"The greatest contribution of the book to analytic aesthetics is that by examining the black aesthetic tradition, Taylor invites us to rethink how aestheticians and philosophers of art have approached the aesthetic tradition in general." - Adriana Clavel-Vazquez, University of Hull - The British Journal of Aesthetics, Volume 59, Issue 2, April 2019

Preface and Acknowledgments

Between Baraka and Brandom

“I don’t know where to begin (or, it turns out, to end) because nothing has been written here. Once the first book comes, then we’ll know where to begin.”

Barbara Smith, “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism”1

I went into philosophy because I thought it would help me help others think more productively about black expressive culture. This seemed like an important thing to do during the early days of the US post-civil rights era, in those days after world events had undermined the idea that, as Du Bois might say, the walls of race were clear and straight, but before it had seriously occurred to anyone to toy with thoughts of post-racialism. At that moment, black expressive culture – the aesthetic objects, performances, and traditions that defined blackness for many people as surely and as imperfectly as skin color or hair texture do – still seemed important in the ways that the US Black Arts Movement had insisted it was. But the old reasons for assigning it this importance had lost some of their purchase, and the old contexts for creating, experiencing, and understanding black expression were undergoing rapid and radical transformation.

The old reasons for focusing on black literature, film, music, and the rest were artifacts of earlier regimes of racial formation. Prior to the (qualified) successes of the twentieth-century black freedom struggles, black expressive culture mattered to blacks because culture work allowed them to escape, to some degree, more than aspirants to success in business or politics could, the yoke of white supremacist exclusion, and to achieve at a level commensurate with their talents. So blacks could look to entertainers and artists as emblems or defenders of their human possibilities. Black culture workers could show self-doubting blacks as well as negrophobes of other races the true potential of unfettered black strivings, and they could defend the race against the racist images and narratives that dominated western culture. At the same time, black expressive culture also mattered to people of other races, even anti-black racists of other races, and also for a handful of reasons. For some, primitive blacks had their fingers on the pulse of some quintessentially human impulses that over-civilized people of other races had forgotten. For others, blackness could be a symbolic field for working out their own identities and impulses, consciously or unconsciously. For still others, and most simply, blackness was associated with dimensions of human experience that are always of wide interest – it was exotic, titillating, dangerous, and sensual.

This dialectical struggle of colonial and anticolonial approaches to blackness began to lose its relevance after African countries became self-governing, and after black subject populations in settler colonial states began to assert and win something like their full citizenship rights. Put simply: Once Oprah becomes a global media icon, and Toni Morrison wins the Nobel Prize for literature, and Mandela becomes the president of South Africa, and Obama becomes the president of the United States – perhaps better: now that Tim Story can direct summer blockbuster films like The Fantastic Four (for good or ill), and Halle Berry can win an Oscar (more on this later) and headline her own tentpole superhero film (Catwoman), and Okwui Enwezor can curate Documenta and the Venice Biennale, and Michael Jordan and Jay-Z can, like Oprah, become global icons for their skills as performers and as businesspeople – once all of this happens, the old approaches to black expressive culture seem much less pertinent. Why ask culture workers to uplift and defend the race, in the minds of black folks or others, when the work of vindication, in aesthetics and in ethics, has already been done?

Many of the particular developments that I cite above were still some distance in the future when I decided philosophy was relevant to black aesthetics. But the general drift was clearly discernible, as was a widespread incapacity to think intelligently about the cultural dynamics that our new racial orders had unleashed. We were starting to see the import of questions like these: How should African Americans orient themselves to icons of African identity, like kente cloth, especially since those icons had specific meanings to participants in specific African communities, and these meanings were often invisible to people looking through the lenses of US racial politics? Does it make sense to demand that black artists produce “positive” images of black life, now that there is less need to defend ourselves against assaults like Birth of a Nation? Does the widespread adoration of figures like Michael Jordan and Michael Jackson, or, now, of Will Smith and Beyoncé Knowles, mean that racism is over? What does it mean that the most lavishly compensated participants in black practices are often white people? How can we even make sense of the idea of “black practices” after the collapse of classical racialism? Worse, how can we make sense of this idea after explicit racial domination gives way, thereby removing the impetus to close ranks and ignore both the differences between the many distinctive ways of being black and the centrality of interracial exchanges to even the most iconic “black” achievements? And what do we make of the strange ambivalence with which black bodies are still widely regarded, which leaves them both invisible and hyper-visible, desired and despised?

Those questions are only more pressing now, in the world after Quentin Tarantino, Joss Stone, and Justin Beiber, a world populated by symposia on Black Europe and Body Politics2 and by Japanese reggae artists who trek to Brooklyn and Kingston in search of authenticity.3 They are pressing in part because they represent a kind of changing same, though not the one Baraka invites us to contemplate. None of the phenomena I’ve gestured at are new, exactly, which means that we have to account for their persistence. But they are still interestingly distinct from the precedents that we might cite for them, which means that we have to explain the difference between, say, Tarantino and Norman Mailer, Beiber and Elvis Presley, Sidney Poitier and Denzel Washington.

Anyway, as I keep saying, I dimly perceived that these were things worth thinking harder about, in ways that seemed, in my experience, either of little interest to or beyond the capacities of most people. I knew that there was a long tradition of serious reflection on black aesthetics, though that description of the enterprise had become available only recently. And I knew that the tradition had even more recently made its way into the academy, into English departments and programs in cultural studies and other places, carried there by people benefiting from the same political victories that now made it necessary to interrogate the shifts in black culture. My hope was to extend the tradition and join the ongoing conversations, and to do so by bringing the tools of professional academic philosophy to bear on our shared problems.

What I did not adequately understand was the degree to which professional philosophy – the part of the profession into which I had been socialized, anyway – had purposely walled itself off from the places and people with whom I wanted to be in conversation. This turned my desire to join the conversation into an attempt to bridge discursive communities – more precisely, to build a bridge from a particular network of discursive communities, the ones that raised me, to the mainland of inquiry into black aesthetics. And that subtle but profound shift in the project has led to the book that you now hold.

I want to be clear about this background because it bears directly on the structure of the project as it stands. I have recently found myself calling this an exercise in “retroactive self-provisioning,” which means that I have tried to write the book that I’d wanted to read, back when the size of the gap between the work I was prepared to do and the work I wanted to do began to become apparent. So the shape of the project, its proximity to contemporary Anglophone philosophy and its distance from – though not refusal of – the veins traditionally mined by other approaches to black expressive culture, is a function of autobiographical contingencies and vocational choices. I undertook this project in part to fill a void in the expressive and theoretical resources of the intellectual traditions that inform my work, and to dissolve the dilemma that I once thought I faced: study philosophy, or study black expressive culture?

The void that I mention is doubly overdetermined. On the one hand, I was trained by analytic philosophers, and found while in their tutelage that I was interested in classical US thinkers like Emerson, William James, and John Dewey, and in the uses that people like Rorty and Putnam found for their ideas. I found further that following out the latter tradition in the right directions could lead me into productive encounters at the more accessible edges of “foreign” traditions, as represented by the likes of Foucault, Butler, Bordo, and Cavell. This sort of training, which was more ecumenical than it might have been, tends not to inspire curiosity about the likes of Amiri Baraka. On the other hand, I had long nurtured an interest in black critical thought. This began during my time at an HBCU (historically black college and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.3.2016 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Foundations of the Philosophy of the Arts |

| Foundations of the Philosophy of the Arts | Foundations of the Philosophy of the Arts |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Ethnologie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | aesthetic politics • Aesthetics • African American • American Philosophy • Analytic philosophy • Art & Applied Arts • Ästhetik • Ãsthetik • August Wilson • authenticity • black aesthetics • black culture • black preachers • black theory • Cultural Nationalism • Du Bois • essentialism • Expression • Fascism • Hybridity • kinetic orality • Kunst • Kunst u. Angewandte Kunst • Philosophical aesthetics • Philosophie • Philosophy • Philosophy of Race • Philosophy Special Topics • Political Philosophy • Primitivism • Purity • racial oppression • retentions • Socialist Realism • Social Philosophy • Spezialthemen Philosophie • Surrealism • The Black Atlantic • the ethnographic present • Toni Morrison • Transnationality |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-32869-8 / 1118328698 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-32869-9 / 9781118328699 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich